“Steps from the ocean!” “Waterfront views!” That’s how the ad in the local yellow pages described The Starlight Hotel, that late great fleabag that enjoyed its real heyday during the twenties and thirties, before everything went to hell. Oh, it was never like the grand palaces that lined the boardwalk further uptown, with their stained glass windows facing the water, the sounds of their orchestras drifting out over the ocean. No, The Starlight Hotel was the crown jewel of the honky tonk part of town, a pink stucco building that stood out from the weathered bungalows that lined Comanche Street, jalousied windows covered with sateen awnings, tasseled umbrellas shielding the cocktail tables on the small piazza, where people of interest came in taxis under cover of darkness and never signed their real names to the register. It was a discreet location where bellboys could be bribed to bring back a bottle of gin fresh off the boats during the prohibition years, where (local legend had it) Starr Ames, the silent screen actress, ended her life after Franco Giselli told her she had been a Goddamned fool to think that he, a practicing Catholic with six kids, would ever leave his family for an over-the-hill hussy such as herself. They found Starr in the bathtub, eyes staring up at the tin ceiling, polished toes peeking out from the bloodied water, palms lank, but curiously turned upward, as though waiting for a fortune teller to come along and read her life line. It was this faded tragedy that started The Starlight Hotel’s slow decline, so that by the seventies, like the rest of Elephant Beach, it stood drenched in decay, the stucco walls flaked and chipped under coats of white paint used to deflect the sun, sateen awnings shredded or sold, jalousied windows missing panes, art deco screens scratched and shattered, and the once festive piazza now a weed-choked, vacant lot with a few rusted patio tables that once held gaily striped umbrellas. It was said that even the ghost of Starr Ames, glamour gal of the silent stage and screen, done in by talkies and Brandy Alexanders, wouldn’t deign to haunt the penthouse on the top floor, where she’d taken her final bath; it chose, instead, to walk the shoreline in bare feet, holding a pair of Ferragamos in one hand and a white fox fur (a gift from Franco Giselli) in the other, singing at the top of her lungs, “I got something, something, something, for my baby and he for me, we got something, something, something, yeah! My baby and me.”

But, over the years they never did change the ad in the yellow pages, and we used to scream with laughter, wondering what would happen if some family from Elmhurst or Philadelphia, even, lured by the promise of waterfront views and proximity to the beach, pulled up in their station wagon expecting a brief respite from the city heat and found instead—well, The Starlight Hotel. What would they think, we wondered, seeing the collection of funky losers sitting out front in their sagging beach chairs, with their fifty cent sunglasses and torn visors, the cracked and calloused soles of their yellowed feet tipped toward the sun? There was Silvester, palsied from some unknown malady, who would stutter into the lounge after a day at the track, waving a fistful of bills, crowing, “It was a cool, cool, pigeon blue, and my baby rode it all the way home”; Jay, a retired English teacher who could read tea leaves and write letters of recommendation for the price of a Schlitz; and Amos, a leathery specimen who, when drunk, would give away his silver rings and then stagger up Comanche Street, screeching, “Which one of you Goddamn bedbugs stole my jewels?”

And if the family was brave enough to venture inside, what would they make of the nameless waitress who wandered the halls hoisting an empty tray high in the air with one arm, stopping random visitors to ask, “May I take your order?”, then turn abruptly to continue her solitary sojourn? Or the young mother with three children who lived on the ground floor and would go out at night, leaving her babies asleep in one bed underneath an open window, their bare bottoms dotted with mosquito bites the shapes of tiny half-moons, as if waiting for someone to walk up Starfish Alley and steal them? And Roof Dog, the mangy German shepherd who lived in the hotel and would make his way up to the roof if someone left the door open, howling long and loudly as he galloped from one end to the other?

Well, where else were they all going to live in such sordid splendor for three dollars and fifty cents a night? The Starlight may have been little more than a flophouse, but the rooms were saved by the water views and the smell of the ocean crouched right outside the windows, and the gaily colored Japanese lanterns strung around the ceilings, whose dim glow provided reading light and hid the true crustiness of the surroundings. Because of its proximity to the Comanche Street beach entrance, it seemed somehow less sinister than it would have in the city, say, or on a more isolated stretch of road. And because of that proximity, and the cool, dim lounge with its long mahogany bar, and the cheap drinks, and Len, the bartender, who was generous with buybacks, and a jukebox that played an eclectic mix of Santana, Frank Sinatra, The Doors and The Wild Irish Tenors, among others, and because of some bizarre notion we had that hanging around a seedy dive with marginal lunatics made us somehow superior to our high school counterparts, with their pastel, split-level palaces and Velveeta lives, that last summer before everyone left, The Starlight Hotel became our headquarters, our nocturnal home away from home. It was where Billy Mackey stayed when his parents discovered the stash of quaaludes beneath the loose floorboard in his bedroom and threw him out; where Kenny and Joanie Kramer held their wedding reception when it became clear her parents wouldn’t contribute a nickel after finding out she was three months pregnant; where Carlie Slattery slept the night of her miscarriage so that she could bleed safely on the hotel’s moth torn sheets without her mother finding out. It was where I thought I might find my mother, not the one who stood in the doorway of the bathroom while I applied lip gloss before heading out to Comanche Street, screaming that someday I’d regret this attraction to the seedy side of life, my father had a master’s degree, for God’s sake, but the mother who had given me up for adoption when she was sixteen years old, younger than I was that final summer. The Starlight Hotel seemed exactly like the kind of place a woman who’d given birth to an illegitimate daughter would be living, and on graduation night, while everyone was dropping acid or smoking angel dust or snorting heroin in the men’s bathroom, I wandered, lightly stoned, through the vacant hallways, dreamily pushing open doors to empty rooms, imagining my mother lying down on one of the lumpy double beds, her long hair fanning down the stained chenille bedspread, her flesh smooth and uncurdled against the flimsy slip she was wearing, gazing up at the ceiling while the smoke from her cigarette curled out the open window. I would be standing at the foot of the bed, and she would rise slowly and stare at me, at my hair, my face, the shape of my nose, and then she’d smile wide and hold out her arms, and say, “If I knew you were going to be this beautiful, I never would have let you go.”

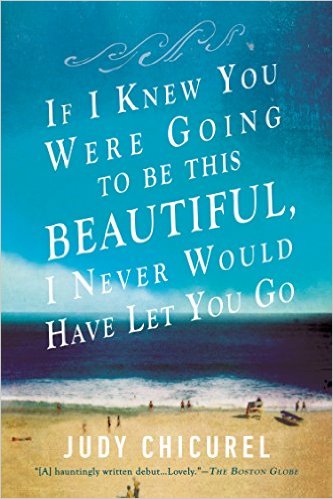

From IF I KNEW YOU WERE GOING TO BE THIS BEAUTIFUL I WOULD HAVE NEVER LET YOU GO. Used with permission of Berkley Press. Copyright © 2014 by Judy Chicurel.