If Consciousness Isn't A Stream, How Do We Represent It?

How Literature Reflects our Changing Understanding of Consciousness

What is consciousness? For literary studies the most influential framework has been William James’s “stream of consciousness.” “Consciousness,” he wrote, “from our natal day, is of a teeming multiplicity of objects and relations [ . . . ]. Such words as ‘chain’ or ‘train’ do not describe it fitly as it presents itself in the first instance. It is nothing jointed; it flows.” In combination with Henri Bergson’s similar notion of durée, James’s emphasis on consciousness’s rich, interwoven nature had a profound influence on modernist depictions of interiority. Reviewing the earliest installments of Pilgrimage, Sinclair summarized the novel (approvingly) with the description, “Nothing happens. It is just life going on and on. It is Miriam Henderson’s stream of consciousness going on and on.” Edmund Wilson similarly praised James Joyce’s Ulysses for finding “the unique vocabulary and rhythm which will represent the thoughts of each” character.

In these accounts, the stream of consciousness is praised for its elimination of narratorial mediation and for transmitting directly the entire contents of characters’ minds, not just their inner speech. As Lawrence Bowling defined the technique, it is “that narrative method by which the author attempts to give a direct quotation of the mind—not merely of the language area but of the whole consciousness.” Stream of consciousness’s contribution to literature, then, is to show that what characters rationally think is inextricable from all the other sensations, impressions, and thoughts underlying their conscious selves.

However, there are a number of potential problems with stream-of-consciousness prose. First, James’s account actually argues that it is an unsuitable style for art. Insisting that the profusion of unimportant data in the stream’s “undistinguishable, swarming continuum” would overwhelm any legitimate object of interest if left unchecked, he claims what “gives [ . . . ] works of art their superiority over works of nature, is wholly due to elimination.” Here James seems in alignment with his brother Henry’s aesthetic, insisting on literature’s need to circumscribe the endlessly interwoven elements of mind so as to avoid generating “loose, baggy monsters.” And the tool of James’s eliminative process is the “habits of attention.” For him the stream of consciousness and attention serve as opposed poles, the former serving to expand the mental life and the latter to constrict it. As James writes, “without selective interest, experience is an utter chaos.”

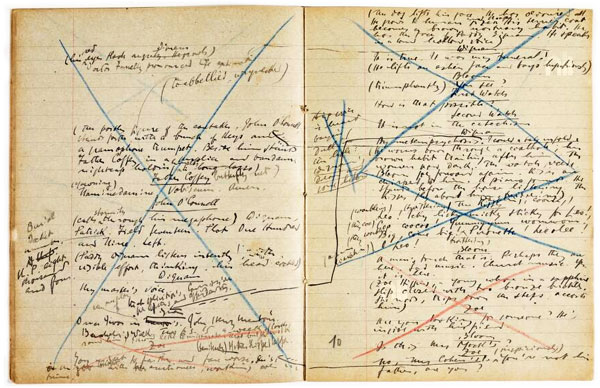

A draft of the “Circe” episode of Ulysses.

A draft of the “Circe” episode of Ulysses.

The ensuing century of research on consciousness, meanwhile, has questioned whether consciousness can be conceived as a linear stream at all. While many regard the question of whether we are conscious of something as a strictly binary question—that is, either we are or we are not, without intermediate grades—most conceptual schema regarding consciousness include multiple levels, rather than a single stream. Even though Antonio Damasio’s “movie-in-the-brain” metaphor for consciousness is relatively assimilable to a stream, he adheres to a distinction between core consciousness (i.e., integrated momentary awareness of time and place) and extended consciousness (i.e., a cross temporal sense of self and possibility). Bernard Baars’s global workspace theory, meanwhile, uses the metaphor of a theatrical spotlight that can illuminate anything on a large stage (but will emphasize only a small area at a given time) for consciousness rather than a stream, identifying the dimly lit areas surrounding the spotlight as “fringe consciousness.” Hardline materialists, like Daniel Dennett, reject the idea of a stream entirely, pointing to experiments in change blindness to suggest consciousness is “gappy” and possesses only the “apparent continuity” of a stream, generated largely from post hoc rationalizations that reconcile “multiple drafts” of experience.

The basic problem is terminological. Since the mind is multilayered, and each layer functions in part by suppressing what occurs at other layers, what is contained by the term “consciousness” will often be less an empirical question than one of whether a given theorist wishes to include certain experiences within the concept. We can see this problem within James’s own work, as his desire for an inclusive stream leads him to include elements of the mind that are clearly nonconscious: for instance, he defines the stream as comprising the manifold of our “sensations” and “thoughts” but admits there are many sensations of which “common men never become aware,” which would imply we are not conscious of them. This inclusiveness threatens to negate the entire concept of “consciousness” by eroding its ability to discriminate between conscious and nonconscious mental contents. Similarly Dennett’s insistence that our inability to register blind spots demonstrates that conscious continuity is illusory is countered by those like Gerald Edelman and Giulio Tononi, who insist that since consciousness has the ineluctable phenomenal appearance of continuity, that continuity (illusory or not) must be an aspect of consciousness.

There are several other tricky cases. For example, we experience dreams both phenomenally and neurally as if they we were conscious, yet dream-states lack conscious elements like wakefulness and sensory response—so are we conscious when we dream? If we only notice the humming air conditioner when it turns off, or the squirrel across the street when it starts to run away, or the missing keys in front of our eyes after five seconds of staring blankly at them, where do they fit? It is difficult to say, but any act of exclusion will tend to move our definition closer to the abstracted rational thought that the stream of consciousness is designed to theoretically counterbalance, and any act of inclusion will gradually erode the special phenomenal status of consciousness as distinct from nonconscious brain activity.

In literary theory and practice, those interested in the stream of consciousness tend toward expansiveness. Literature, it is often suggested, ought to be “consciousness-raising,” a view rooted in Viktor Shklovsky’s defamiliarization, which rails against the human tendency for life to become automatic and nonconscious. “After being perceived several times,” he writes, “objects acquire the status of ‘recognition’ [ . . . ]. We know it’s there but we do not see it, and, for that reason, we can say nothing about it.” Shklovsky’s goal is that conscious perception grow at the expense of nonconscious processing, a desire shared by the various aesthetes and ideological critics who have proselytized for defamiliarization. One prominent example is the recent vogue for a theory of the everyday, which, in Michel de Certeau’s words, desires that “everyday practices, ‘ways of operating’ or doing things, [should] no longer appear as merely the obscure background of social activity.”

“Much as there is no scientific consensus as to what constitutes consciousness, there is no literary consensus as to how to write it.”

Yet this attitude, it turns out, is problematic, because increased consciousness is not an unalloyed good. Consciousness is resource-intensive when compared to nonconscious activity, and actions associated with conscious mental states tend to be less skilled than nonconscious ones. This may sound counterintuitive, but it should make sense to anyone who has worked steadily to improve at an instrument or game: you perform best when you perform without thinking. To make oneself as conscious as possible, then, is to hinder general skillfulness. If one really tried to be mindful of every dish one washed, every step one took, every key one pressed, life would become impractically cumbersome.

That is why most theories of the everyday tend toward contradiction: for something to be part of the everyday means for it to be habitual and hence nonconscious; to construct a theory of it, though, is to pay special attention to it and give it conscious meaning, removing it from the everyday. As you can practically make only so much conscious, attempts to formulate the everyday tend to crash into either the Scylla of Henri Lefebvre’s overdetermined Marxist pomposity (e.g., “All we need to do is simply to open our eyes, to leave the dark world of metaphysics and the false depths of the ‘inner life’ behind, and we will discover the immense wealth that the humblest facts of everyday life contain”) or the Charybdis of Certeau’s disparate mumblings (“one can follow the swarming activity of these procedures that, far from being regulated or eliminated by panoptic administration, have reinforced themselves in a pro- liferating illegitimacy [ . . . ] combined in accord with unreadable but stable tactics to the point of constituting everyday regulations and surreptitious creativities”). If we are to pay attention to any previously everyday aspect of life, then, it had better be because there is a particular reason to devote conscious energy to it rather than because we want to increase consciousness indefinitely.

As literary theorists have argued for some decades, novelistic prose is the most refined method we possess for depicting consciousness, and all reading comprehension requires both conscious effort and selective attentional focus. Consequently consciousness’s inherently messy terminological status will cause those attempting to depict it to produce divergent prose styles. That is likely why even the most canonical, consensus examples of stream-of-consciousness writing have few common formal characteristics. Here are excerpts from the three texts perhaps most associated with the technique. First, Proust’s madeleine:

Will it ultimately reach the clear surface of my consciousness, this memory, this old, dead moment which the magnetism of an identical moment has travelled so far to importune, to disturb, to raise up out of the very depths of my being? I cannot tell. Now I feel nothing; it has stopped, has perhaps sunk back into its darkness, from which who can say whether it will ever rise again? Ten times over I must essay the task, must lean down over the abyss. [ . . . ]

And suddenly the memory revealed itself. The taste was that of the little piece of madeleine which on Saturday mornings at Combray (because on those mornings I did not go out before mass), when I went to say good morning to her in her bedroom, my aunt Léonie used to give me, dipping it first in her own cup of tea or tisane. [ . . . ] But when from a long-distant past nothing subsists, after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, taste and smell alone, more fragile but more enduring, more immaterial, more persistent, more faithful, remain poised a long time, like souls, remembering, waiting, hoping, amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unflinchingly, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection.

Second, Leopold Bloom approaching Dignam’s funeral in the “Hades” episode of Ulysses:

Gasworks. Whooping cough they say it cures. Good job Milly never got it. Poor children! Doubles them up black and blue in convulsions. Shame really. Got off lightly with illnesses compared. Only measles. Flaxseed tea. Scarlatina, influenza epidemics. Canvassing for death. Don’t miss this chance. Dogs’ home over there. Poor old Athos! Be good to Athos, Leopold, is my last wish. Thy will be done. We obey them in the grave. A dying scrawl. He took it to heart, pined away. Quiet brute. Old men’s dogs usually are.

Third, Peter Walsh crossing Regent’s Park in Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway:

A sound interrupted him; a frail quivering sound, a voice bubbling up without direction, vigour, beginning or end, running weakly and shrilly and with an absence of all human meaning into

ee um fah um so

foo swee too eem oo—

the voice of no age or sex, the voice of an ancient spring spouting from the earth; which issued, just opposite Regent’s Park Tube station from a tall quivering shape, like a funnel, like a rusty pump [ . . . ].

Through all ages—when the pavement was grass, when it was swamp, through the age of tusk and mammoth, through the age of silent sunrise, the battered woman—for she wore a skirt—with her right hand exposed, her left clutching at her side, stood singing of love—love which has lasted a million years, she sang, love which prevails, and millions of years ago, her lover, who had been dead these centuries, had walked, she crooned, with her in May [ . . . ].

These are all closely focalized depictions of mind, but there are few similarities among them. Proust’s passage registers the close relationship between sensory stimulation and memory, but Marcel’s perfectly structured sentences evidence a highly refined, attentive reconstruction that suppresses the immediate conflicts and confusions that our raw sensations engender. We see the latter more vividly in Ulysses, where the sensory input of the gasworks sets off a series of clipped, associative sentences that carry Bloom fleetingly across thoughts about illness, advertising, and his father’s dog—yet Joyce must conversely suppress those aspects of consciousness (emphasized by Proust) that can observe and articulate the more complicated aspects of its own processes. Woolf’s sentences, meanwhile, are as long as Proust’s but as twisting as Joyce’s, depicting consciousness less as a private matter than an intersubjective state that floats from Peter to the narrator to the demented old woman to (just beyond the end of this passage) Rezia Warren Smith, without obvious break. It would be a stretch to map any of these literary depictions of consciousness directly onto the models of consciousness described above, but much as there is no scientific consensus as to what constitutes consciousness, there is no literary consensus as to how to write it.

__________________________________

From The Cruft of Fiction: Mega-Novels and the Science of Paying Attention by David Letzler, published by University of Nebraska Press. Copyright © 2017 by David Letzler.

David Letzler

David Letzler is an independent scholar. His essays have been published in Contemporary Literature, Studies in the Novel, the Wallace Stevens Journal, and the African American Review.