I was a seventeen-year-old pornographer.

That’s how a young assistant prosecuting attorney introduced me to a sleepy Manhattan night court judge as I stood before him in the wee hours of the morning on July 3, 1969. I had been arrested the afternoon before, but because the DA’s vice squad detectives didn’t know in which downtown Manhattan precinct to book me, we were too late for day court, and so I was held in the adjacent jail known as the tombs until the night session began around 8:00 p.m.

Since the docket was full of petty criminals, prostitutes, and drug dealers, I didn’t go before the judge until two in the morning. I spent hours being moved from one overcrowded holding cell to another—like passing through the digestive tract of the criminal justice system—until I was finally spit out into a brightly lit courtroom.

I was the art director, designer, and copublisher of the New York Review of Sex & Politics, an odd mix of New Left politics, puerile humor, and sexploitation. NYRS&P had grown out of the underground newspaper the New York Free Press after it was discovered that the Freep only sold out when nudes (preferably women) were put on its cover. Like staff at the other New York undergrounds in 1969 (the East Village Other and Rat), we at the Free Press started a sex paper to subsidize our political publication. However, after a month or so of simultaneous publishing, we reluctantly folded the Freep and devoted our energies to the sex paper.

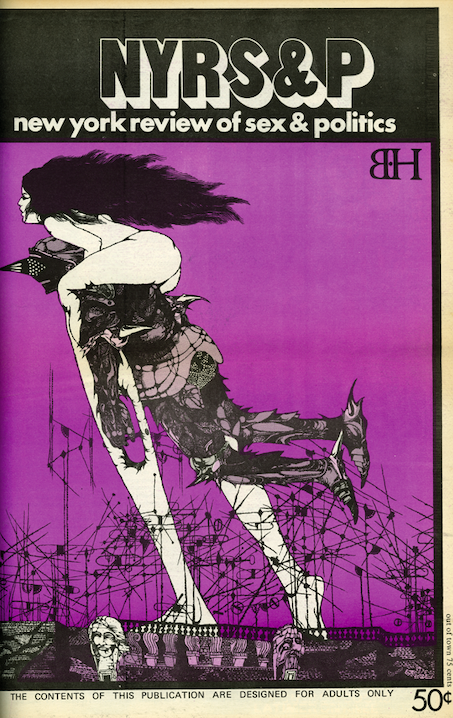

New York Review of Sex and Politics, October 15, 1969. Brad Holland refreshed the type and used only illustration in the next four issues. Co-publisher and art director: Steven Heller.

New York Review of Sex and Politics, October 15, 1969. Brad Holland refreshed the type and used only illustration in the next four issues. Co-publisher and art director: Steven Heller.

I was pasting up our fourth issue when we received a telephone call. “That was the DA’s office,” said the office manager nervously. “They said that you, Sam, and Jack [the editor and copublisher, respectively] were under arrest and should not leave the premises.” Sam Edwards was on an errand, and Jack Banning had absconded with all the money in our bank account a week before and couldn’t be located.

I broke into a cold sweat. I was alone and underage. I called our lawyer. He was in a meeting and couldn’t be disturbed. “I’m about to be arrested,” I told the secretary frantically.

“I’ll give him the message,” she said calmly.

Next, I called our distributor, a nasty little man whose relatives were related to the infamous Murder, Inc. mobsters during the thirties. His secretary said that he had been called by the DA’s office and had left the premises.

Finally, I called my father (I still lived at home). He was out too. For God’s sake, where was everyone? I told his secretary to tell him I was being arrested and would probably be home late for dinner.

Like staff at the other New York undergrounds in 1969 (the East Village Other and Rat), we at the Free Press started a sex paper to subsidize our political publication.The moment I hung up the phone, two detectives entered the office. Both looked surprisingly familiar. I had seen the young one on the TV news a few nights before talking about investigating the mob in New York. The heavyset one had come by the office a week before to buy copies of the newspaper. He claimed to be an adult bookseller from Long Island. They showed their badges, read me my rights, and asked the whereabouts of my two partners. I told them I had no idea. I asked if I could go to the bathroom. They came with me while I tied my shoulder-length hair in a ponytail just in case the stories I had heard about goings on in jail were true. I asked if they wanted to handcuff me; they said no, unless I was planning an escape.

As I sat between them in the front seat of their unmarked car, they informed me that all the sex-paper publishers and distributors were being rounded up. “We figured you’d all be at Woodstock,” said the heavyset one. He had heard on the radio that the rock festival, which began that day, was attracting thousands of people. “I would like to go,” admitted the young one, but he said he had to work. “I decided to work this weekend, too,” I volunteered, although I really had planned on going.

They asked me exactly what I did. The question seemed innocent enough that to reply without a lawyer being present would not jeopardize my case. “I’m the art director,” I said.

“What’s that mean? Do you photograph the models?” asked the heavy one.

“No, I design the format, pick the typefaces, crop the pictures, buy the illustrations, paste-up the mechanicals, and sometimes work the typesetting machine, and I get paid very little in the bargain,” I said.

During the time it took to find the booking precinct and then get us down to the courthouse for arraignment, the young one and I developed a good rapport. He told me that he really didn’t want to arrest me, or any other art director; he was after the mob. He detested the mob and pledged to disrupt as many of its operations as possible. “But we’re not mobsters,” I said. “Maybe our distributors are, but all newspaper distributors, restaurant suppliers, and private trash disposal companies are mob run. We’re just trying to publish an underground paper that takes jabs at authority and hypocrisy.” I told them that my Murder, Inc. distributor accused me of being the only person in New York who could make a sex paper fail.

We learned that these roundups of publishers and distributors were intended to be harassing enough to put us out of business, because the DA really had skimpy legal grounds for censoring our publications.Incidentally, the issue they were busting us on was called “Our Especially Clean Issue.” The only vaguely hard-core sex photograph in the issue was an ad for Screw (four months earlier, I had been the first art director of Screw). Everything else was not only soft-core but no-core; the hottest picture in the issue was a fully clothed woman in a raincoat sitting on a fire hydrant. Nevertheless, some good citizen had complained to the DA’s office about the sex papers, and that was impetus enough for the vice squad to take action.

When I reached the jail, a few of my elder colleagues from the other sex papers had already been processed and were ready to make their courtroom appearances. My arresting officers hastily tried to get me through the clogged system, but without success. When the court authorities found out I was still a minor (my eighteenth birthday was only days away), I was put through even more red tape before I was allowed to appear in court. As a minor, I could not be in the male criminal holding cells, so I was placed in a pen with the prostitutes until I was called before the judge. While I scarfed down their bologna sandwiches and Kool-Aid (that day’s holding-pen rations), they teased me and played with my ponytail until my name was called. When I entered the courtroom, I found that my distributor had provided a lawyer, and I was released without bail pending trial.

New York Review of Sex, cover, July 15, 1969: “Our Especially Clean Issue.” This edition was busted for pandering by the Manhattan District Attorney. Photographer: Mario Jorrin. Illustrator (back page): Roger Tomlinson.

New York Review of Sex, cover, July 15, 1969: “Our Especially Clean Issue.” This edition was busted for pandering by the Manhattan District Attorney. Photographer: Mario Jorrin. Illustrator (back page): Roger Tomlinson.

In the period between my arrest and trial, I was arrested again in another roundup. This time I was eighteen, and the process was not as much fun. My elder partners and I were placed in a huge holding cell full of drunks, vagrants, and petty crooks. My partner Sam, always the comedian, even tried bartering me for a few cigarettes, but mercifully without success.

We learned that these roundups of publishers and distributors were intended to be harassing enough to put us out of business, because the DA really had skimpy legal grounds for censoring our publications. No matter how sexy and sexist they were, the DA could not prove they were pornographic. Indeed, one of the indictments against Kiss, the sex paper published by the East Village Other, cited an R. Crumb cartoon for obscenity. The cases against all the papers were thrown out of court, but only after a costly legal battle.

Art direction was a mighty dangerous job.After our second arrest, the New York Review of Sex & Politics was on its last legs. Our distributor gave us an ultimatum: either we include enough hard-core sex to interest a viable readership or he’d fold us. Our response was to add “& Aerospace” to the already cumbersome title, include even more political content, and ultimately call the publication the NYRS&P (& Aerospace)—not even mentioning sex in the title.

My mentor Brad Holland designed the first new NYRS&P cover using an illustration that was so softcore that the paper looked somewhat like its unprofitable forerunner, the Free Press. Brad designed and illustrated two more. I did the final cover, spelling out the title with a cropped art photo of a very beautiful nude Black woman. The distributor cut us off and the paper died.

Nevertheless, I was still under indictment. I still had to appear in court on porn charges. And I still faced a possible prison sentence if convicted. Art direction was a mighty dangerous job.

By this time, we had a reputable First Amendment lawyer, Herald Price Fahringer, who was paid by our former distributor. Herald later went on to defend the tabloid favorites Jean Harris, who killed her lover, and Claus von Bülow, who poisoned his wife. (He lost both murder cases.)

Herald’s strategy was to petition a three-judge panel prior to our initial trial on the grounds that the NYRS&P and Screw were unlawfully censored, citing prior restraint. The judges had to determine whether the DA was indeed harassing us or, based on the content of the paper, had a reasonable cause for confiscating issues and arresting principals.

They were also to determine whether each issue could be reviewed by judges before warrants were issued, or if that was also unconstitutional. The legalities were complex, but fundamental. Somehow during the blitz of briefs and testimony, it was determined that the DA did not adhere to the law, and we were exonerated on all charges before going to trial. The NYRS&P had folded, and I returned, after a year hiatus at Rock magazine, to art direction at Screw.

As art director I could help Screw pass muster if ever it was judicially scrutinized by maintaining a high level of design and illustration to offset the truly awful photography.Winning this case meant that New York City and New York State legal authorities left the sex papers alone, and Screw took every opportunity to see how far that tolerance could be stretched. During my two-year tenure as art director, the legal actions against Screw were minor. But shortly after I left my stint, the feds indicted Screw in Wichita, Kansas (the hub of the US Postal Service) for pandering through the mail. This was not taken lightly, since Ralph Ginzburg, former publisher of the legendary Eros, had been found guilty and imprisoned on similar charges.

Given my experience, I knew that before Screw could be convicted for pornography it must be proven that it was void of any redeeming social value, which, without excusing its rampant sexism, it had. It was a journal of cultural criticism pegged to sex. I knew that as art director I could help Screw pass muster if ever it was judicially scrutinized by maintaining a high level of design and illustration to offset the truly awful photography.

Hence, I suggested that Push Pin Studios (Milton Glaser and Seymour Chwast) redesign Screw in 1971, which they did, though badly. Milton designed a clever visual pun for the logo, with the middle stroke of the E in Screw turned upward like an erect penis; all the other design letters were corporate-looking Helvetica. The interior layouts were lackluster.

I hired some of the best artists—including Brad Holland, Marshall Arisman, Edward Sorel, Mick Haggerty, Philippe Weisbecker, Jan Faust, Don Ivan Punchatz, and John O’Leary—to draw and paint exclusive illustrations for the covers. Doug Taylor even won an American Institute of Graphic Arts award for one of his covers. Many of the covers were witty commentaries on sex and sexual politics. I took a similar approach to inside art too. Whenever I could, I’d replace bad photography with good illustration. Some illustrations, however, did not live up to that standard and were just plain dumb.

New York Review of Sex and Politics, cover, November 1, 1969. Our distributor argued that these covers designed and illustrated by Brad Holland would never sell on the newsstand.

New York Review of Sex and Politics, cover, November 1, 1969. Our distributor argued that these covers designed and illustrated by Brad Holland would never sell on the newsstand.

My strategy was put to the test when, only a few months after I left Screw for the New York Times, I was subpoenaed to appear first before a federal grand jury and afterward as a hostile witness for the Wichita federal prosecutor in the trial against Screw. Unlike the Warren Commission, these proceedings can now be told. I was warned that if I refused to testify, I would be imprisoned for contempt, yet little did they know I wouldn’t miss this for the world.

When it came time for me to testify, the prosecutor (whose wife mysteriously sat behind his desk in the courtroom knitting a scarf like Madame Defarge in A Tale of Two Cities) showed me large blowups of some of Screw’s more prurient pages taken from two or three issues. He asked me to explain how they were put together, what contribution I made to the makeup, and, most critical to his case, what artistic merit they had. I detailed the way type was set, the distinctions between typefaces, and the decisions that lead to the design. I admitted that some pictures might be distasteful even to me, but that the publication in its entirety had great artistic merit. While reminding the jury I was a hostile witness, the prosecutor tried to prove otherwise.

Under cross examination, Herald also brought forth blowup pages, most from issues that included illustration. He asked what each drawing depicted, who did the drawing, and what was the rationale for using a drawing, not a photograph. Each question was a planned opening to wax poetical about the art, describe the achievements of the artists (that is, Brad Holland appears regularly on the Op-Ed page of the New York Times, does covers for Time magazine, has been honored by the Society of Illustrators and the Art Directors Club, teaches at Pratt Institute, etcetera). With each description of a distinguished artist, the case for redeemability was reinforced and the prosecutor’s case faded away.

After a brief deliberation, the jury brought in a verdict of not guilty. Herald said that calling me as prosecution witness was a major mistake for the feds, because my testimony solidly helped convince the jury to accept the defense of social redeemability. This was the last time I was involved with pornography.

_____________________________

From Growing Up Underground by Steven Heller, courtesy Princeton Architectural Press.