Did someone click on the title? Good. You made it up to get attention. You’re writing this essay about getting attention—to get attention. Your publisher has encouraged you, as they encourage all their authors, to try writing about something related to your life or work in advance of your new novel’s upcoming release. Whether it’s an essay, an autobiographical vignette, or a reading list/article (“listicle”), creating compelling content tied to your book can be a valuable way to catch the eye of potential readers, build name recognition, and maybe capture some of that elusive phenomenon called “buzz.”

You’re a good sport, and you promise to try. The word essay means “try,” after all. The problem, though, is that you’re a fiction writer, and the idea of writing essays (especially about yourself) makes you feel queasy. Nearly all your writer friends share vexation with this part of the publishing process. After all, if you all were good at this sort of thing—if you were extroverts, scintillating personalities—you probably wouldn’t be fiction writers.

You’d be pop singers, Instagram influencers, politicians, memoirists. You got into this line of work because it lets you do what you perversely love best: sitting alone silently for extended periods of time, making things up. You were raised with the impression that fiction writers were allowed to do that, that they had to do that to write good books, and that writing good books led to success. The books spoke for themselves. The writer could stay in her hermit cave and set the book free without needing to follow it out the door.

A writer can have brilliant genius and amazing endurance, but none of it matters if nobody’s paying attention.But this is naïve, and you know it. A writer can have brilliant genius and amazing endurance, but none of it matters if nobody’s paying attention. Without an audience, what’s art? It’s a tree falling alone in the forest. The metaphor seems sadly apt: what a shame, the poor lonely tree, with all its history and beauty, its musical existential crash unheard, as if it had never lived at all. This, you realize in panic, is the panic of all artists.

The problem is that art withers and dies without dissemination. The artist has a dual quest, to create good work and ensure that it’s shared. The drive to create is rooted, after all, in the basic human need for connection. As an artist, you’re compelled not to just to manifest your vision of the world, but to share it with others. Your job is to run your raw perception and experience of the world through the alchemizing mechanism of your own singular, idiosyncratic mind—and then try to package it in the form of something new, inimitable, and alluring that other people will want to pull into their own minds. You might even say that art is a form of reproduction—the reproduction of your own consciousness—and that it’s just as ingrained as biological reproduction, if not always as enjoyable.

Of course, none if this breaking news. You know that as long as there’s been art there’s been attention-seeking. Prehistoric people didn’t carve petroglyphs in remote, hidden places, but on strategic rock faces where they’d be seen by others. There are carvings spanning hundreds of years squeezed together on Newspaper Rock in Utah, where they were most likely to be viewed by a critical mass. As the volume of artists has grown over the centuries, so has the clamor for attention.

During the Renaissance, artists found themselves vying for limited patronage, trying to attract the powerful few who could expand the reach of their art. Such patronage was symbiotic: financial support and publicity were bestowed on those with celebrity or personal charisma—those who showed themselves to be the best publicists for the patron’s own brand, so to speak. This was arguably when artists first began the work of self-promotion in earnest, cultivating individual personas, burnishing their own auras.

And then Romanticism furthered the notion of the creator as an elevated figure, lifting visual artists, poets, and writers to lofty heights, where they were presumably visited by divine inspiration, transcending the realm of mortals. It certainly didn’t hurt for an artist to nurture this mystique. Lord Byron, possibly the first major literary celebrity, shamelessly promoted “Byromania” by publicizing his exploits in love and war and enhancing his physical beauty in polished and artfully posed portraits.

Walt Whitman, too, was a master publicity hound, writing his own rave reviews and posing for down-home photos that illustrated his persona as anointed poet of the common man. In one photograph, a butterfly appears to perch on his finger—implying that even animals were drawn to his earthy emanation. The butterfly was later discovered to have been a cardboard prop. “The public is a thick-skinned beast,” Whitman said, “And you have to keep whacking away at its hide to let it know you’re there.”

Living in the so-called attention economy, we’re immersed in the constant noise of social media, the unrelenting tide of conversation and content.There’s no less pressure for you, today, to whack at the public’s hide, to fashion a personal mythology, or at least drum up some intrigue that might captivate the distractible masses. In our post-industrial world of expanding global links, exploding populations, and exponential spikes in production of everything from lip gloss to selfie sticks to literary fiction, attention is scarcer and more fleeting than ever.

Living in the so-called attention economy, we’re immersed in the constant noise of social media, the unrelenting tide of conversation and content. It’s a babble that never ebbs, pulling at our psychic strings like a never-ending pool party that we can dip in and out of but never really leave. The roar stays in our ears even after we close the computer and turn off the phone. It’s infiltrated our lives so fully that solitude itself has begun to feel like an illusion. There’s a sense of always being watched, alternating with a sense of not being watched, being ignored. It’s this awareness of others that never goes away, the awareness of what or whom they’re paying attention to.

How to function as an artist in this scenario? You, like your writer friends, are hyperventilating. You’re all introspective and maybe a little introverted. You’re paralyzed by the party. Yes, you know that social media is the great equalizer. Never has there been such a democratic avenue for dissemination of ideas, for better or worse, or such an open avenue for self-promotion. It’s an enormous opportunity for those writers with a knack for it. Some of the funnier and quick-witted have built impressive followings.

Some have sold or marketed books based on this virtual audience alone (though it’s still up for debate whether these phantom followers buy many books). But what about you and others like you—so many others, based on your amateur research—who cringe at posting random thoughts to a global bulletin board? What about those of you hesitant to expose your private lives like flashers, screaming “Look at me!”? Every single fiction writer you know has a fraught relationship with social media, too. All of them are disgusted by it and want to quit but feel they shouldn’t or can’t. It’s a time suck, and it makes you feel dirty, but it’s a career responsibility, a shameful addiction, a postmodern ball and chain.

You know—or hope—that social media isn’t the end-all. There are plenty of other ways to expand readership. There’s the old-fashioned power of personal networking, going to parties, schmoozing with people who can amplify a name, lift a career. Some writers are blessed with a glittering built-in persona they can carry from party to party and from book to book: some uncommon background, an extremely interesting or attractive appearance, or pre-existing fame from another career or position. If you don’t have that (and you’re afraid you don’t), you can always manufacture an eye-catching look. Even just adopting a hallmark sartorial choice or visible eccentricity might lay the foundation for legend. You think of Salvador Dalí’s curled mustache and cape, Tom Wolfe’s white suits, Donna Tartt’s tailored shirts and ties, Susan Sontag’s (purposely undyed) streak of white hair, even grouchy Patricia Highsmith’s purse full of snails.

Failing all this, you might find a look—or rather a hook—for the work itself, whether it’s a subject of perpetual interest or some newly hot social topic. It’s too late to do this in your new book, of course, and anyway the latter strategy is nearly impossible to carry off. Nailing a hot topic means having the psychic foresight to write compelling and deeply-felt fiction about that topic far enough in advance that its publication will land at precisely the right moment—sailing through the window of peak interest before the culture moves on. Given the tortoise pace of writing and publishing, this is like hitting a moving target in the water pistol game at a carnival, if you were aiming the pistol from inside your car in the parking lot.

So, where does this leave you, self-pitying ordinary fiction writer, without fame, a fascinating background, uncommon beauty, schmoozing finesse, or social media chops? Where does leave you and your self-pitying ordinary friends for whom self-promotion is nauseating, who write stories that interest yourselves, hoping your universal themes might also interest readers? You yourself are personally unremarkable, maybe a regular lady in the suburbs who does laundry and vacuuming, walks the dog, and helps with math homework. You only wear a cape on Halloween. No snails crawl out of your purse, unless it’s a toy one you’re carrying for your kid. Can’t you just write books and hope the right readers find and love them?

“You have to blow your own horn,” your mother always told you. Nobody’s going to come knocking on your door to discover your talents. Growing up, you were mortified by this. You’d always been under the impression that modesty was a cardinal virtue. When it came time to apply to college, write a resumé, and go on job interviews, it went against every fiber of your being to blow your own horn. What you’d accomplished seemed insignificant compared to what others had done and what you wanted to do. It felt wrong, fake, to promote yourself based on such a weak showing. You still feel this way, and you still think modesty is something to be valued. Maybe you’re old-fashioned, but to your mind it’s a species of kindness, an unwillingness to put yourself above others. It’s a demonstration of respect and belief in the equal value of lives. Your experience, your accomplishments, are no better than anyone else’s; only different.

And yet. Deep down (or not so deep), don’t all artists (at least sometimes) believe they’re geniuses? Doesn’t it take mind-blowing arrogance to write a book? Don’t all creators seek acknowledgement, approval, praise, and yes, fame? You tell one writer friend that you just want to keep publishing books, not be on the Today Show. “But don’t you?” she asks. Well, don’t you? Maybe you do. Maybe it’s disingenuous to pretend otherwise. Maybe it’s stupid to sit back and hope, like a wallflower at a dance, too self-effacing or aloof to jump in the fray. Maybe the unapologetically ambitious, the naked climbers, the entitled and egotistical are the only honest ones—and the only smart ones—out there.

You remember being bewildered by the aspiring art star in college who mounted a show of nude self-portraits during freshman parents’ weekend and who nearly knocked you down to get at the boy you were casually seeing. Only later did you realize the boy was some sort of heir, and that she was deep in a long-game—now exhibiting at the MoMA. Maybe those are the people who stick in the history books, just like Whitman and Byron.

The truth is that attention-seeking is both anathema and integral to art. You know there’s a double imperative to dive inward, creating deeply considered work, and to push outward, wading the shallow waters of promotion. Even when fully removed from the world, toiling deep in your hermit cave, there’s still the hope for an audience, a yearning for it. The only way to create anything true is to believe that no one’s watching, that no one will ever see it—but at the same time, the very act of making art infers the existence of someone else experiencing it. It’s a paradox: creating into obscurity and into the spotlight at once.

To bring it back to Kierkegaard (as you too often insufferably do) the act of creation is an act of faith akin to Kierkegaard’s Knight of Faith, the absurd figure who’s capable of embracing the finite and infinite at the same time. To create art, what’s necessary is an utter belief in both mortality and immortality, an insane conjunction of humility and arrogance. This lunatic dance of the artist isn’t really so different from the dance of ordinary living, you think. We all move through impossible waters, functioning day to day despite crushing despair at the suffering of the world. We all create and affirm life amidst unrelenting destruction. We erase ourselves in deference to the world’s largeness and assert ourselves as part of it, in equal measures. We’re all artists to some extent, subsisting on attention: both receiving it and giving.

To create art, what’s necessary is an utter belief in both mortality and immortality, an insane conjunction of humility and arrogance.As it happens, all your writing is ultimately about this. On the surface, maybe your new book is about rich white people in the suburbs doing rich white suburban things. It’s about ennui, motherhood, frustration, infidelity—the antithesis of a hot topic. But maybe it’s also about environmental degradation, the tendency to hide from the climate crisis and impending doom. It’s about the power of art in the face of catastrophe. And at the core, your novel—and all your work—is about the mandate to create and connect. You’ve always been drawn to writing about art and artists in particular—yes, because writing lets you dream up artworks without buying and dealing with art materials—but also because you’re interested in characters who are desperate to connect. It’s crucial to their lives. Without creative engagement, they languish and stumble into other means of producing friction, often destructive ones.

At heart, you know that it’s a universal human urge to make a mark, to rage against irrelevancy and mortality, to be noticed and remembered. The miracle is the mark—the transmission of one mind to another, the holy act of paying attention, the infinite process of human cross-pollination. The miracle is the persistence of that mark beyond your own life span, its continued ability to command attention from the living, to assure them that those who came before were much the same as they are, and that those who come after will inherit the same set of loves and losses and mysteries. Art is both memento mori, a reminder of our impermanence—and salve, a reminder that we’re not and have never been alone.

And so, in the end, isn’t this the measure of what you want to say—about your work, about writing, about yourself? Well then, here’s your essay. Now, where’s your cape?

___________________________________

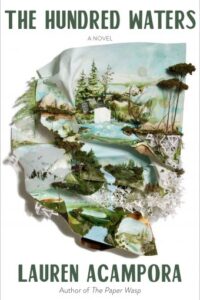

The Hundred Waters by Lauren Acampora is available from Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic.