He could hear the squeaking of chairs, as the glassy-eyed recruits tried to concentrate but couldn’t, their attention drifting to the balmy temperature outside the barracks, the beach, and better days. He tried to engage them, infusing humor into his recitation of past imperfect, continuous past, simple past. His students seemed distracted. Or perhaps he was the distracted one, as his novel gestated within him. He could feel it kicking.

“I am, you are, they are . . . ,” he continued. One of his students smiled meekly, his body language begging the instructor not to call on him. No more than twenty years old, he reminded the instructor of his father when he was young and handsome, before he turned into the stranger who flitted about his home. Corporal John Kennedy Toole felt pity for the student, who, like most of the young men stationed at Fort Buchanan in Puerto Rico, had volunteered for military service so they could feed their families. Most were from the mountains and work was scarce. These boys weren’t patriots. They were kids sitting in a sweltering room, trying to learn enough English to survive the battlefield. They were hoping it wouldn’t come to that, just as their instructor was hoping he could get this damn novel out of his head and onto paper. So, there they were, a couple dozen boys who hadn’t yet known the horrors of war, because if they had, they’d sure as the sun would set not be sitting in those desks, and the instructor knew this, knew that if he didn’t put his whole heart into teaching these kids English, they could die one day, and it would be his fault. These were his recruits. They were counting on him even if they didn’t know it.

“I am!” he said, loudly this time. “You are!” Then he told them to repeat it. “Again,” he said. “Again!” The recruits seemed surprised by the sudden burst of intensity but did as they were told, while the instructor willed himself to stay on task, as characters he hadn’t fully formed danced and fretted to be loosed onto a blank page.

It is November 1961. John F. Kennedy has been president for nearly a year. The Soviet Union has just conducted the largest nuclear test in history and Americans are building bomb shelters while the beatniks preach peace and love. The Orient Express makes its last journey from Paris to Bucharest as a generation of babies discover the first disposable diaper. Construction has begun on the Berlin Wall while the Professional Golfers’ Association tears down another when it eliminates the whites-only rule. It is a world struggling to adapt, caught between old-school values and the demands of an aggressive new era.

Corporal John Kennedy Toole surveyed his classroom. Tall and handsome, with a strong handshake and refined Southern manners, he was a gentleman’s gentleman, an anomaly in this place. Always perfectly groomed, smelling of clean, fresh soap and Brylcreem, Corporal Toole always strived to set a good example for his students. He felt a kinship with them. Admittedly, they were uncultured. His mother would have been appalled by their lack of manners, their disregard for all things of beauty and grace. His mind was drifting again. “Focus,” he thought. “Focus on these young men.” All he could hear was his mother’s voice, invading, always invading his thoughts like the damn mosquitos here, the size of birds. Ignatius would have stormed about the barracks complaining.

Corporal Toole suddenly began to experience gastrointestinal distress. Or wait, was that Corporal Toole or Ignatius? It was getting to the point he couldn’t tell the two apart. Sometimes he found himself in a situation in which he’d normally be cool and calm, an ordinary circumstance by any civilized person’s definition, and then Ignatius would pop out like a rotund, black-haired jack-in-the-box, spewing opinions. When he’d become excited, his large round eyes would bulge, animating his face.

Ignatius was more than a fictional character to his creator.

He was the person John Kennedy Toole wanted to be.

“Sir, you alright?” asked the same young man who reminded him of his father.

“Yes, I’m afraid I got a little distracted,” the instructor said. “I’m working on something in my free time and it does vex me.”

The boy looked at his superior and smiled knowingly, even though he wasn’t certain what vex meant. A good Catholic boy whose mother had raised him to be polite, he didn’t want to disappoint her here in an army barracks where all he could think about was how much he missed everyone back home.

“Sir, what is vex?” asked another recruit sitting toward the back. This boy was different from the rest. He had a curiosity his superior officer admired, a desire to be something more than a poor kid who was only in the army because there weren’t any other options. The instructor explained vex to him. The recruit nodded, listening intently. The corporal wanted to take his class in another direction that particular morning, teach his students something of substance, not just have them conjugate verbs so they could learn military commands that washed the humanity clean out of them. This corporal didn’t believe in war, didn’t believe in upheavals or bloodshed. If he wanted war, he could go back to Audubon Street in New Orleans and listen to his mama. That was Ignatius, he was the one who thirsted for revolution, who conspired to impose geometric symmetry and moral decency upon the masses. Ignatius was itching to teach the corporal’s class that morning, but the corporal held his ground. This was his class and he wanted to introduce his students to the things his mama had taught him to appreciate: the theater, great literature, music.

__________________________________

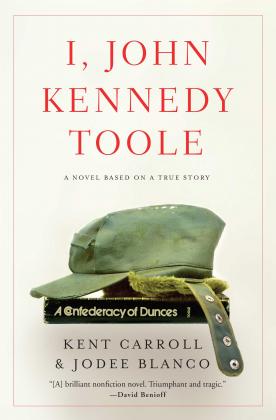

From I, John Kennedy Toole by Kent Carroll & Jodee Blanco. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Pegasus Books.