How Writing a Novel Helped Me Say Gay

Jules Ohman on the Truths That Her Fiction Uncovered

In an early draft of my novel, two 18-year-old girls who had once been close friends have a dramatic falling out on a Portland rooftop. As I wrote the scene, in which one of them demands the protagonist say something, do something, while they’re both looking out at the shining Willamette River, on the very edge of whatever’s coming, I kept asking myself—staring at my laptop screen—why was she mad? What wasn’t the protagonist doing? I couldn’t make the emotional arc of the chapter make sense. I didn’t know what was missing.

I was 22 and had just started grad school. I was growing out a (very gay) buzzcut but had been in a straight long-term relationship since I was a teenager. I’d had silent, longing crushes on queer friends in high school and college, but I didn’t have a label for what that feeling meant.

No adult around me had ever said “gay” at all, even in the suburbs of Portland, Oregon, where I grew up. When I was a kid, I was drawn to books written by queer writers, but no one ever pointed that out to me, and for years, I’d written short stories about queer characters without ever calling them that or use the word to describe myself. I’d grown up in the 90s and aughts, when “Don’t Say Gay” was, for the most part, a nationwide agreement, and now that I was an adult, I couldn’t say it either. I couldn’t even think it.

Somewhere in that chapter it came to me. They liked each other, but only one of them had the words for it. Their relationship was intimate in a specific way, but to one of them, it was undefined; the protagonist couldn’t see that her friend was in love with her. She didn’t know what it felt like. She couldn’t even imagine it. It mirrored my own experience as a teenager without me being able to put a finger on it. Despite all the longing, I was always on the side of the crush where I didn’t quite know what was going on, where I feared any defining of it. Like the protagonist, I was unable to move forward, make a move, say it. Often, all it would have taken was saying it. But I couldn’t, and so nothing happened.

No one can erase queer narratives, as much as some want to. We’re writing them every day.

When it came time to workshop the chapter, I realized two things: other people would read this, and I didn’t care. I could describe queerness in fiction, write scenes full of a thousand gay things, and not feel like it was about me or my identity or what that meant. It was fiction!

Grad school was full of out queer writers, and my friends there became the first people to see me clearly and in context, even before I was able to. From the beginning, everyone just assumed I was queer; at our first gathering, a picnic where queer people were the majority, I was growing out the buzzcut and wearing a well-loved Horses t-shirt with androgynous icon Patti Smith slinging a suit jacket over her shoulder. I was self-conscious, but secretly pleased to be noticed in this way, by this community. I’d always paid more attention to my identity as a writer, but not as a person, and didn’t recognize what all that silence had done to me. Even when I was in a community that felt relatively safe, it took time to overcome years of not-naming.

For two years, I workshopped the novel, but I was also workshopping myself. I wrote a scene where the protagonist kissed the girl. I wrote a chapter where they slept together. Then, I did those things in real life, too. It was easier to do it first in fiction, and then in life; it was safer to describe it in detail before attempting to do it myself. I was writing myself an emotional blueprint, pacing the story at a safe speed. On the page, I could avoid labels altogether—instead, I could describe bodies, feelings, relationships.

I finished a draft of the book, but it was nowhere near done. When my agent regularly gave me notes like, “But how does she feel here? You’re avoiding saying something important,” I wanted to tell him, I don’t know! I don’t even know what I’m avoiding! Those feelings had been so buried that I didn’t even know where to begin digging until I was being pressed in the margins to explicitly think about it. But eventually, I started to. I had to, for the sake of the novel. For myself.

Fiction also gave me more nuance to describe what my gender felt like in an embodied way. My gender had always been queer, masculine of center, and as my protagonist grappled with how her androgynous body could move through the world, I grew more comfortable with that myself. I’d always drifted in and out of the men’s section—a zone that felt magnetic but taboo—and eventually, I stopped drifting out of it. I let myself pick out men’s jeans with deep pockets, t-shirts, and sweaters without any flare, and lace up boots with no high heel. The last dress I ever wore was to my college graduation, one my mom, in trying to get me to wear it, described as “as not-a-dress as a dress can get.” Even a not-a-dress dress felt terrible.

I wrote my protagonist reaching a sense of peace with the ambiguity of her gender, and then I did too.

From then on, I wore button downs, or suits. I grew my hair out, cut it off to a crew cut, grew it out again. For years, when I’d asked for a short haircut, hairstylists didn’t know what to do with me and I was too embarrassed to describe to them what I wanted, which resulted in a lot of pixie cuts whose long, femininizing pieces I later cut off with craft scissors in the bathroom of my apartment. But when I moved back to Portland, I could ask for something as specific as a butch bob, and the stylists knew what I meant. I wrote my protagonist reaching a sense of peace with the ambiguity of her gender, and then I did too. I wrote my protagonist falling in love with a musician, and then I did too.

Over time, my protagonist’s love interest became more like my girlfriend, now wife, not the other way around: the thick calluses on her fingers from playing guitar, the openness she has toward the world, our ease together. The queer community in the book became more like my own community: their jokes and taste in music, their endless kindnesses.

Finally, I had reached a place where I was living it first and writing it second.

*

The same year I started writing my novel, I began teaching creative writing to teenagers. I was only a few years away from high school myself, and it felt radical to teach the poems and short stories that I wished I’d been given, and to ask the students what kind of narratives they wanted to read. In the last decade, the kids I’ve worked with have become more comfortable saying who they are and asking for books that reflect their experiences. This is because students, educators, and parents have done enormous work since I last attended a public school in 2009. None of my teachers ever said gay, even in Portland, a place where I have found immense queer community as an adult, a place known for gender-affirming healthcare and LGBTQ+ rights.

Many of my friends came out in their late twenties, thirties, and forties, because we had to unlearn years of conditioning that the anti-LGBTQ+ bills currently gaining momentum in conservative legislatures are trying to codify. They are attempts to keep both kids and adults from naming who they are and therefore from being it. These bills, which assault the rights of trans kids and their families, are passing in state after state, all of them aiming to silence and erase. They are telling queer kids that they shouldn’t exist, that their stories don’t matter. They are trying to censor selfhood.

Over time, almost all the characters in my novel became queer: the protagonist’s brother, her childhood friend, her mentors, her new friends. By the time the book was done, no one was asking me how my protagonist felt anymore. It was on the page. Out in the world, I could say it and I could live it.

No one can erase queer narratives, as much as some want to. We’re writing them every day. We find ourselves anyway. But it could be—it should be—easier.

__________________________________

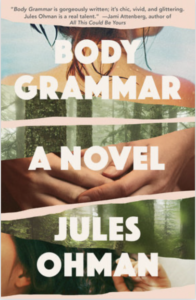

Body Grammar by Jules Ohman is available via Vintage.

Jules Ohman

Jules Ohman received an MFA from the University of Montana and cofounded the nonprofit Free Verse. She coordinates Literary Arts' Writers in the Schools program and lives in Portland, Oregon, with her wife.