Aeschylus presents the most compelling version of Clytemnestra in his play, Agamemnon. It begins with Clytemnestra awaiting her husband’s victorious return from the Trojan war. She has spent ten years planning her revenge for Agamemnon’s murder of their daughter Iphigenia, whom he sacrificed to the goddess Artemis to obtain her favor and fair winds to sail to Troy. When Agamemnon appears outside the royal house of Argos, he has brought with him the Trojan priestess, Cassandra, as a slave—so we know his attitude to the gods is blasphemous at best.

Clytemnestra tricks Agamemnon into entering their palace walking across priceless tapestries, again the behavior of a man who believes himself equal to the gods. She slaughters him when he is most vulnerable, after he has bathed and has no weapon, no armor. She also kills Cassandra, who has foreseen her death but is resigned to it. Clytemnestra and her lover (and Agamemnon’s great enemy), Aegisthus rejoice in the killings and the play’s chorus—the old men of Argos— are appalled at both the crime and their vicious delight. Clytemnestra dismisses their complaints as trivial and ends the play in a position of strength and jubilation. It won’t last, as the chorus predict in the plays later moments: the second part of Aeschylus’ trilogy will see a terrible revenge taken on Clytemnestra by her surviving children.

Clytemnestra is usually presented as an archetypally bad wife. The only question tends to be her motivation, which makes her more or less sympathetic, more or less threatening to the society which depicts her. Our earliest descriptions of her are in the Odyssey, where she acts (in narrative terms) as a dark reflection of the archetypally good wife, Penelope. The poem follows Odysseus on his extended journey home to his long-suffering wife, while she copes with the invasion of her home by a gang of young men, the disrespect of her son and plenty more. She is held up throughout Greek myth as a model wife to her absent husband.

But the story of Agamemnon’s homecoming punctuates the poem, not least when Odysseus visits the Underworld in Book Eleven and meets his now-dead comrade. He asks Agamemnon how he died, whether Poseidon had wrecked his ship or whether he’d been killed by men whose livestock he was trying to pilfer. Magnificently, Odysseus manages to conjure up scenarios he himself has experienced and will experience: his heroic self-absorption is an ever-present risk to his own (and his men’s) survival in this poem.

Agamemnon says no, it wasn’t Poseidon and nor was he killed by men defending their land. It was Aegisthus, he says, with help from my wife. He uses the vocabulary of ritual slaughter, just as Clytemnestra will go on to do, in Aeschylus’ play. The Homeric version is more of a bloodbath, however: this Agamemnon saw his men slaughtered too, like pigs. He then compares it to a battle, which makes the domestic details all the more shocking: palace tables stacked with food and wine, the floor beneath them covered in blood. He says he heard Cassandra being killed by Clytemnestra while his own life ebbed away. Clytemnestra didn’t even look at him as he died, did not even close his eyes and mouth after death. He advises Odysseus to return home cautiously, although he does also suggest that Penelope isn’t the murdering kind, “not like my wife.”

So Homer’s Clytemnestra is not quite as terrifying for men as Aeschylus’ version: she doesn’t kill her husband, although she does stand by as he is killed and has been involved in planning his murder. Obviously for women, and specifically for Cassandra, she is precisely the same degree of murderous. And for the Homeric Agamemnon, Clytemnestra’s affair with Aegisthus is the root of her evil. There is no suggestion that this might be avenging the death of her daughter, or indeed that she might have political ambitions to rule in her husband’s stead, both of which were part of her character in Aeschylus. At least as far as Agamemnon tells things here, she was solely motivated by desire for Aegisthus. Clytemnestra is nothing more than an adulteress.

Clytemnestra is usually presented as an archetypally bad wife. The only question tends to be her motivation, which makes her more or less sympathetic, more or less threatening to the society which depicts her.It is this motivation which will come to define Clytemnestra when Roman authors get hold of her. For Ovid, in his Ars Amatoria or The Art of Love, she is driven by sexual jealousy, which only really manifests itself when she sees Agamemnon’s infidelity up close. She stays chaste while she can imagine Agamemnon is faithful to her. She heard the rumors about Chryseis and Briseis (both women whom Agamemnon had claimed as war brides in the Iliad).

But it is only when he returns home with Cassandra, and Clytemnestra sees the relationship for herself, that she begins her own revenge-affair with Aegisthus. So Ovid is continuing a tradition which deprives Clytemnestra of her status as queen and Fury, but he also removes the responsibility for Agamemnon’s murder from her. The implication is that Agamemnon is responsible for his own downfall: if he had had the good sense to keep his mistress away from his wife, he might have lived to a ripe old age.

Of course, Ovid is writing a very different kind of poem from Homer’s epic Odyssey or Aeschylus’ tragedy Agamemnon. The Ars Amatoria is a bright, racy, jokey guide to having illicit sex in Rome (produced at a time when the new emperor, Augustus, was cracking down on adultery. At least, other people’s). So Ovid has every reason to turn Clytemnestra and Agamemnon into a suburban couple whose swinging habits get out of control, rather than treating them with the epic grandeur of our earlier Greek authors.

Here we find no reference to Iphigenia, no reference to Clytemnestra’s designs on the Argive throne. Ovid knows so much about Greek myth that we know he is being deliberately cheeky here: reducing Clytemnestra—and Medea, a little earlier in the same passage—two famously wronged women who respond with remarkable violence to their abuse—to little more than vexed housewives kicking up a fuss.

The Roman philosopher and playwright Seneca must have read Ovid’s treatment of Clytemnestra, because his version of her (in his strange, flawed play, Agamemnon) is a similarly sexual being, tormented by her love and intense desire for Aegisthus. She does mention Iphigenia, but not with any particular anguish or need for retribution. As with Ovid’s interpretation, the Senecan Clytemnestra is jealous of her husband’s sexual conquests while he has been away at Troy: Briseis, Chryseis and Cassandra. But unlike our earlier Clytemnestras, this one is afraid that her husband will punish her for her own indiscretions. She even considers suicide. We have come a long way from the fearless, furious woman created by Aeschylus.

But let us return to Clytemnestra in her raging Aeschylean incarnation. More specifically, let’s follow her story through to its end. The second play of the Oresteia is The Libation Bearers. This is a reference to the offerings made at the tomb of the late Agamemnon by Electra and the chorus some years after the events of the previous play. Clytemnestra has been having bad dreams and she believes the ghost of her late husband needs placating. She has sent her daughter Electra to do the honors. Electra prays for her long-absent brother Orestes to come home and avenge their father. We learn that Clytemnestra still rules with Aegisthus.

But Electra is about to have her wish fulfilled: she identifies a lock of hair left as an offering beside her father’s tomb, and she sees a footprint which seems remarkably familiar to her. She concludes that both hair and footprint belong to Orestes, and that her brother must have returned at last. If this seems like a bit of a leap, you are not alone: Euripides mocks this whole recognition scene in his later version of the same story, Electra.

But once the siblings are reunited—along with Orestes’ companion Pylades—they determine to take action against their father’s killer. Orestes has been ordered by no less an authority than the god Apollo to do so. Clytemnestra comes out of the palace to greet these two men whom she believes to be strangers. She welcomes them inside, offers them hospitality. Orestes doesn’t identify himself, instead pretending to have met a man who had news for her: that Orestes is dead. Her response is that of a mother who has lost her son, rather than a woman who fears retribution from him. You’ve stripped away the thing I love, she says: I am utterly destroyed.

Once they get inside the palace, Orestes kills Aegisthus, but wavers before killing his mother. Clytemnestra realizes she is to be killed by someone who has used trickery, just as she herself had used it to kill. For a moment, it seems as though Clytemnestra will talk herself out of trouble: I gave birth to you, she says. I want to grow old with you. He is aghast at her words: after killing my father? You want to grow old with me? She blames Moira—Fate—for Agamemnon’s death.

And then she and Orestes share a moment which must resonate with parents and children in less extreme circumstances. You cast me out, he says. She sees things differently: I put you at an ally’s house out of harm’s way. I was sold into slavery, he replies. Oh really, she says: how much did I get for you? We can surely hear the echoes of parents and teenagers arguing through the ages: they agree on the events which have occurred, but their interpretations of those events are poles apart and neither can see the other’s point of view. Mother and son are, in this moment, uncannily alike. But Pylades has reminded Orestes that Apollo demands this retributive killing, and Orestes does as he has been told. Clytemnestra dies reminding him that hounds of vengeance will chase him down.

*

And so they do. There is one more play to come in this trilogy: The Eumenides, which means “Kindly Ones,” a new name for the Erinyes, or Furies (following the theory that, if you give something a nicer name, it may behave less alarmingly). This final play poses and answers one simple question: was Orestes justified in killing his mother? The Furies, who pursue him relentlessly, think he has committed the unforgivable crime of matricide. But Apollo, and then also Athene, take Orestes’ side: he had a moral obligation to avenge his father and matricide was the necessary consequence of doing so. Whatever we might feel about the question, the play resolves the issue to its characters’ satisfaction: Orestes is acquitted thanks to divine intervention, and the Furies—grudgingly—allow him to continue his life unmolested.

But the play’s resolution does raise another question in our minds: why is Agamemnon’s life valued more highly—by everyone except Clytemnestra—than Iphigenia’s? Why was Agamemnon not pursued by the Furies for the unforgivable crime of killing his daughter? Why was it left to Clytemnestra to avenge her? Why do Electra and Orestes have so much more respect for the wishes of their dead, murderous father than for their living, murderous mother, and indeed their dead, blameless sister?

Even if we agree with the conclusion that the trilogy reaches (which is that this cursed family must stop taking matters into their own hands and should instead air their grievances in a court and abide by the verdict —in this case supplied by a goddess), we are surely left thinking that Clytemnestra had a point, way back in the first play, when she asked the chorus why they were so upset by Agamemnon when they were so unconcerned about Iphigenia. It’s him you should have banished, she told them. It seems that Clytemnestra seals her own fate when she values her daughter’s life equally to the life of a king.

One final note: in Euripides’ play Iphigenia in Aulis, which tells the awful story of Iphigenia’s death, Clytemnestra mentions that she had a first husband, before Agamemnon. His name was Tantalus, and she tells us that Agamemnon killed him and married her himself. She appears to have had no say in the matter of marriage to her husband’s killer. And not just her husband. Because Agamemnon also took her baby, an infant which she was nursing when Agamemnon appeared. He wrenched the child from her breast by force and smashed it into the ground. In other words, in this play (and other, later sources will pick it up), Agamemnon kills two of Clytemnestra’s children, more than a decade apart.

And while many later authors will drop this element of her story, and focus on her adultery rather than her maternal rage, it is there for us to see in astonishing, dramatized clarity in fifth-century bce tragedy, and especially in Aeschylus’ Oresteia. He probably did not invent this aspect of her motivation (it is in an ode by Pindar which was likely composed a few years before Aeschylus’ plays were written, although it is possible it was a few years later). So Clytemnestra is a byword in the ancient world, and ever since, for a bad wife, the worst wife even.

But for wronged, silenced, unvalued daughters, she is something of a hero: a woman who refuses to be quiet when her child is killed, who disdains to accept things and move on, who will not make the best of what she has. She burns like the beacon she waits for at the beginning of Aeschylus’ Agamemnon. And if that means men think twice about drinking from a wine cup with her murderous rage depicted upon it, so be it. She would—at least in Aeschylus’ depiction—relish their fear.

____________________________________________________

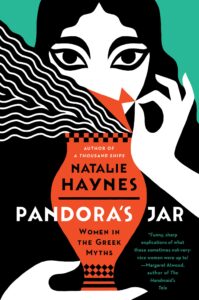

Adapted from Pandora’s Jar: Women in the Greek Myths. Copyright © 2022 by Natalie Haynes. Reprinted here with permission from Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.