How Two Telephone Books Tell a Condensed Story of the Holocaust

Miljenko Jergović on the Visible Erasure of Croatian Jews

Croatian culture has dealt with the fate of the Jews in WWII in sporadic fashion. If and when the subject was considered, it was always in a wider, European context, while locally, our own Holocaust was avoided like a dirty conscience. Aside from individual documentary accounts and testimonies of the survivors, the subject of the Holocaust practically doesn’t exist in Croatian literature. It was a taboo to some, to others perhaps an unimportant matter, and after 1945 there were no longer any great Jewish writers, dramatists, or poets in Croatia. Unlike Serbian literature, whose great writers—Danilo Kiš, Aleksandar Tišma, Đorđe Lebović, and also Ivo Andrić in his emblematic story “The Titanic Bar”—have written about the Holocaust, and Bosnian literature, which has the Jewish storyteller Isak Samokovlija in its canon.

We begin to understand why Croatia has been mum about the Holocaust a little after the publication of the first works devoted to the fate of Zagreb Jews: Ivo Goldstein’s “The Holocaust in Zagreb” and “Jews in Zagreb,” books met with flaming hatred or scornful silence by the better part of the public, the right-wing media, Croatian National Television, and in academic and ecclesiastical circles, while the author found himself on various informal blacklists.

These books led to Goldstein’s intellectual isolation and erasure from the nation. Goldstein is no longer perceived as a Croat, nor is he seen as a Croatian historian. This is believed not only by open nationalists, but also by a majority of Zagreb’s unemancipated burghers, who react viscerally to such books.

The story of Croatian Jews can be reconstructed quite reliably. One can get a glimpse of the fate of various individuals, along with the names and surnames of those who merely assisted in their demise. All it takes is a peek in the telephone book.

I bought my 1941 Telefonski imenik, the telephone directory published by the Ministry of Post, one Sunday in the summer of 2008, at an antique fair in the British Square, and paid 600 kunas for it. Six months later, in a now closed antique shop, I picked up a copy of the 1942 directory, now called Brzoglasni imenik, for the territory of the Independent State of Croatia. The book cost 380 kunas, though I would have gladly paid ten times more, because, as I’d been looking for it everywhere.

I had a premonition that it represented, a moving testimony about the Holocaust in Croatia, as well as the social and cultural changes that took place in Zagreb between the end of 1940, when the phonebook for 1941 was printed, and June 1941, the date of completion of the 1942 volume.

The design of these two books suggests that for a well-to-do Zagrebian, Croat, Catholic—in those days only well-to-do citizens had a telephone—almost nothing had changed between 1940 and 1942. The phonebooks look almost the same: on their fine, orange covers they bear the same advertisement, for Schneider’s Music Shop at 10 Nikolićeva Street, the “biggest specialized company in the state,” where one could buy a “Hohner, the most perfect accordion in the world,” as well as all other instruments and musical paraphernalia. It was owned by Franjo Schneider, who, apart from the shop also owned a luthiery workshop and a lumber shop. In addition to the official number listed on the cover he also had a private one for his place of residence at 107 Bukovačka cesta. Unlike some other Schneiders, Franjo Schneider was a Catholic.

The first observation that arises from a reading is that the Croatian government segregated its citizens on the basis of religion and ethnicity thoroughly.

The same advertisement for Siemens telephones is on the back cover of both phonebooks, together with the slogan “Telefon – your versatile assistant,” which would subsequently be altered to read “Brzoglas – your versatile assistant,” while the “Yugoslav Public Limited Company Siemens” became the “Croatian Public Limited Company Siemens”. There were no other edits except telefon was transformed into brzoglas: “Siemens brzoglas stations are a result of concentrated research. They convey wholly intelligible speech, even under most unfavorable conditions.”

The first observation that arises from a reading of the two directories is that the Croatian government segregated its citizens on the basis of religion and ethnicity in a thorough fashion. It took them barely two months—from the establishment of the state to the drafting of the phonebook—to strip Jewish telephone subscribers of the right to brzoglas and assign their numbers to other people. Telephone directories were made, even back then, to be serviceable, so it’s possible to search them both by number and by name.

In the 1941 directory, Dr. Stjepan Deutsch, father of the thespian wunderkind Lea Deutsch, lived at 29 Gundulićeva Street. In the next tome, the brzoglas number is listed under the name of Dr. Jozo Poduje as his private number at his residence at 2 Jurjevska Street. As an advocate, Jozo Poduje was hardly unknown to the burghers of Zagreb. He was the president of the Rotary Club; we can still find his name on the lists of notable Croatian and Zagrebian Rotarians. It’s worth asking ourselves what Poduje thought, how he felt, when he was given the number which, at a time when Jews were still allowed to use the telephone, had belonged to his colleague Stjepan Deutsch.

The great Croatian architect Rudolf Lubinski was the designer of the magnificent National and University Library building in Mažuranić Square which today houses the Croatian State Archives, as well as the new Sephardic synagogue in Sarajevo, the Templ, which became a concert venue after WWII, acoustically one of the finest in Yugoslavia. He died in March 1935. But his number at 2 Plemićeva Street was still in the phonebook for 1941. His descendants, possibly, continued to live there. The following year his brzoglas number went to dentist Josip Ribić, from 3 Pejačević Square. Who knows if dentist Ribić’s phone ever answered his phone and heard a voice from Chicago or Buenos Aires asking after the Lubinskis? What would Josip Ribić have said in response?

Dr. Miroslav Šalom Freiberger was chief rabbi of Zagreb. He didn’t want to leave the city while it still had Jews left in it, so he was sent to Auschwitz in 1943 and executed. He lived at 8 Ambruševa Street. In the next telephone directory we find the rabbi’s telephone number listed among the brzoglas numbers of the Croatian National Assembly, under the subheading “People’s Deputies.” The Assembly had thirteen phone lines, one each for the speaker, the notaries, the quaestors’ office, assembly chamber lobby, quaestors’ office registry, library, diplomatic reception room, the stenography office and the aforementioned people’s deputies. What may have happened if someone called and asked to speak to Rabbi Freiberger?

The Zagreb Pen and Pencil Factory was built on the foundation of the company “Penkala – Moster” established in 1906 on inventor Eduard Slavoljub Penkala’s genius and Edmund Moster’s capital. The Mosters were a wealthy Jewish family from Zagreb who owned a paint and varnish factory. Edmund’s brother Mavro lived at 37 Kukuljevićeva Street. The following year, his brzoglas line was used by a clinician, Dr. Ivo Galić, from 25 King Stjepan Tomašević Street. His brother Bernard, owner of a chemical plant on Heinzl Street, lived at 13 Mesnička. Anyone dialing his number a year later would be put through to the Department of General Affairs of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, headed at the time by Ustashe war criminal Dr. Andrija Artuković. The third brother, Aleksander Moster, managed, until Hitler came into power, a family company in Berlin that produced writing utensils. Those who dialed Aleksander’s number the following year had the honor of discoursing with Lady Anka Grabarska Gvozdanović from 8 Visoka Street. But we’ll never know what Lady Gvozdanović said when someone phoned and asked to speak to Mr. Moster, perhaps thinking that her ladyship was his secretary.

The name of the most famous of the brothers, Edmund Moster, doesn’t appear in the 1941 phonebook. He was either discreet and hid behind a number registered in another name, or he had an official number only. There were still people like that at the time. But we do know how Edmund Moster, industrialist, philanthropist and inventor from Zagreb, met his end. In 1942 he was murdered in the Jasenovac death camp. His brother Bernard was killed that same year in a concentration camp on the Croatian island of Rab. Aleksander and Mavro were killed as well. But the ballpoint pen, Penkala’s famous invention, to this day remains a point of Croatian national pride and a proof that we’re not any kind of Austro-Hungarian province. Indeed, our countrymen invented a thing used by all of humanity—the ballpoint pen.

Let us look up engineer Slavoljub Penkala. He died in 1922, survived by his widow. Next to the name Emilija Penkala it says “spouse to engineer Penkala.” At the end of 1940 her address was King Petar Square (Yugoslav Academy). That’s precisely what it says, and it would mean that Mrs. Penkala lived at the Academy. The following year something was different. The telephone number was unallocated; next to the number was a blank space. But that doesn’t mean Emilija Penkala was denied a brzoglas line. By 1942, we find her at a rather nice address, 7 Brešćenski Street.

Ashkenazim made up a vast majority of Zagreb Jews ever since the early 19th century when Jews first appeared on the social scene, and had surnames that were rooted in German or Slavicized, often in such a way that Weiss would become Bijelić, and Leibowitz would rename himself to Lebović. As a rule, Sephardim moved to Zagreb from Bosnia and Herzegovina in more substantial numbers after the establishment of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. They came mostly for economic reasons, as Zagreb was more prosperous than Sarajevo or Tuzla, or they came to study and never returned to Bosnia.

In the 1941 telephone book Sephardic surnames aren’t so thin on the ground, and they’re interesting because the Sephardim were not famous or distinguished Zagrebians. It’s safe to assume they didn’t belong to the cultural and political elites, but were still newcomers from the provinces.

So we find three Albaharis: Izidor lived at 7 Klaonička Street. The next year his number went to the Rail Car, Machine and Bridge Factory at 2 Gajeva Street. Mavro Albahari, purveyor of “ropes and rope products,” lived at 15 Martićeva. His was eventually given to Petar Nikolić, “publisher and art dealer” from 20 Gajeva. Mocha Albahari was Izidor’s neighbor in Klaonička Street. In 1941 his number went to Alois Carmine, the new general manager of the expropriated Chromos factory, who lived at 11 Gvozd.

By the end of 1941, there were no more Jewish telephone subscribers in Croatia.

By the end of 1941, there were no more Jewish telephone subscribers in Croatia. In Zagreb, two institutions were an exception: the Jewish Community, which had been evicted from its premises at 22 Palmotićeva Street 22 and moved into a dilapidated, claustrophobic cellar at 4 King Tomislav Square. They had one brzoglas line at their disposal. A year earlier, the number had belonged to Merkur Sanatorium. The other brzoglas that those Jews who had not yet been executed or sent to a camp could use was registered in the name of the Jewish People’s Fund, at 9 Trenkova Street. A year before, the number had been for the office of Dr. Srećko Podvinec. We know nothing of Podvinec’s fate, except that in 1942 there were no more telephone lines registered in his name, either at his former residence at 23 Jabukovac, or at his surgery.

There was one more Jewish brzoglas in Zagreb. In the phonebook for 1942, it says: “Attias Brothers, fine leather goods,” along with the address, 80 Radnička cesta. Attias is a distinctly Sephardic surname, there were no Attiases of Catholic or any other faith. A year prior, in the 1941 phonebook, we find another Attias in Zagreb: Salamon, a “purveyor of hosiery, gloves and knitwear,” on 6 Jurišićeva Street. The Attias brothers’ shop was at the same address. The pre-war owner of that business, Rafael “Rafo” Attias, was a native of Bihać in northwestern Bosnia. He obtained a law doctorate in Vienna, and managed the leather shop. People remembered Rafo’s father Jakob, owner of the finest cobbler’s shop in town. We are not inclined to learn what happened to Rafo Attias in the end. We won’t look him up in the book with the names of the murdered Jasenovac inmates.

It isn’t likely that the Department of Post, Brzojav and Brzoglas of the Ministry of Transport and Public Works took a phone number from a Jew and gave him another one. It is more probable that the Zagreb section of the 1942 phonebook wasn’t updated to include information that a Jewish business had been expropriated on behalf of Aryan, German, or Catholic Croat. In all other cases and in all other sections of the phonebook, the process of expropriation was finished by June 1941, and the relevant section of the brzoglas directory duly updated.

But what happened with the telephone number the Attias brothers used before the war? According to the 1942 directory, it was unassigned. Why were the Attiases given a new one, who had that line before it went to them? Here we come across a name important to both Croatian and Jewish history: Hinko Gottlieb. Before the Ustashe came into power, the number was registered as the number of his law office. Gottlieb was a lawyer and poet, one of the pioneers of Zionism in Croatia, a man of great personal courage and intellectual integrity who regularly represented defendants in political processes in the courts of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. He was in lively contact with Josip Broz Tito, so he can be found in the name index of practically every relevant overview of the history of the Yugoslav labor movement in the interbellum period. But Hinko Gottlieb was no Communist, he was a proponent of a Jewish migration to Palestine, to Eretz Israel, and a leftist of a different kind, in stature and outlook quite close to those European Jewish intellectuals who participated in creating the state of Israel, as well as the early system of kibbutzim, popular communities that were one of the few humane realizations of the original communist dream.

What happened with the pre-war telephone number of poor Salamon Attias, purveyor of hosiery, gloves and knitwear from 6 Jurišićeva Street? His number became the brzoglas number of Mrs. Anđela Gentner, a shopkeeper residing at the same address. Did she take over Attias’s shop? It’s unlikely a Jew would have been granted the privilege to sell his property. Such a thing had been prohibited on pain of death as early as April 1941. If she moved into Salamon’s shop, Mrs. Gentner did so with the Ustashe’s blessing. She took it over as if it were a stretch of liberated territory, assuming full responsibility for that action. What was on her mind, how she justified the eviction and expulsion of Salamon Attias, purveyor of hosiery, gloves, and knitwear, we will never learn. The reason for that is the silence of Zagreb and Croatia about what transpired among us in 1941, a silence that takes on the weight of lead and the force of accusation leveled against anyone who’d ask a question whenever the topic of the Holocaust is brought up.

We also don’t know what happened to Mrs. Anđela Gentner in 1945. The new administration probably reappropriated the shop. If she survived, she had 45 years to grumble, gossip, and curse the communist Yugoslav government, or take delight in the sermons of a combative priest.

How did all those people feel when the phone rang and the voice from the other side asked to speak to someone who was no longer there? The silence surrounding this inescapable question, one that time cannot annul, tells us all there is to know about a society and culture that never rose to assume that basic human responsibility, the cornerstone of all humanhood.

___________________________________________

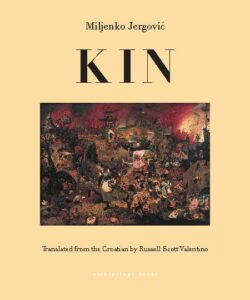

Kin by Miljenko Jergović, translated by Russell Scott Valentino is available now from Archipelago Books.

Miljenko Jergović, translated by Mirza Purić

Miljenko Jergović is a Bosnian and Croatian writer and journalist. One of the most significant Balkan writers of his generation, his writing is celebrated throughout Europe, and his work has been translated into more than twenty languages. He has received numerous literary awards, both domestic and foreign. His landmark collection of stories Sarajevo Marlboro received the Erich Maria Remarque Peace Prize, and his poetry collection Warsaw Observatory received the Goran Prize for young poets and the Mak Dizdar Award. Mama Leone won the highly regarded Premio Grinzane Cavour for the best foreign book in Italy in 2003. And in 2012, he received the Angelus Central European Literature Award for his book Srda Sings At Dusk On Pentecost. Jergović currently lives and works in Zagreb, Croatia.

Mirza Purić is a literary translator working from German and BCMS. He is a contributing editor of EuropeNow and in-house translator for the Sarajevo Writers’ Workshop. From 2014 to 2017 he was an editor-at-large for Asymptote. He has published several book-length translations into BCMS, including Nathan Englander’s The Ministry of Special Cases, Michael Köhlmeier’s Idylle mit ertrinkendem Hund and Rabih Alameddine’s The Hakawati. His translations into English have appeared, or are due to appear, in Asymptote, H.O.W. (blog), EuropeNow, PEN America, AGNI, the Well Review and elsewhere.