How Truman Capote and Andy Warhol's Complex Friendship Marked Them Both

Blake Gopnik and Rob Roth on Adapting the Conversations of Two American Icons for the Stage

Featured image: The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

“her eyes, squinty and bright green…

voice—boy husky

pencil-thin, bony kneed legs”

and

“fiery dutchboy hair

joel height

worn brown shorts and a yellow polo shirt”

Those are a few lines from a whole sheet of notes that an art student named Andrew Warhola wrote, in a knock-kneed cursive he’d just invented, about the characters in a new novel he’d just read called Other Voices, Other Rooms. A twenty-three-year-old Truman Capote had published it early in 1948, seeing it received with both acclaim and disgust—but always with surprise.

The New York Times said Capote was “fascinated by decadence and…evil, or perhaps only by weakness…” and that his book was “filled with sibilant whispering,” hinting broadly at its homosexual themes.

The very special, complex friendship captured by Roth had its roots in where they both came from.

Andy Warhol’s notes on Capote’s novel mark the first intersection between two of the most daringly gay creators in postwar America.

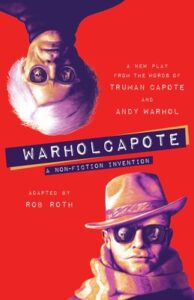

Rob Roth’s WARHOLCAPOTE, based on words actually spoken by the two men, is set in the 1970s and ’80s, toward the end of their close connection and not too long before their untimely deaths. But the very special, complex friendship captured by Roth had its roots in where they both came from.

When Capote’s book appeared, Warhol was all of nineteen, a junior in college in his native Pittsburgh. He was also just coming out as gay, in a city whose judges soon declared homosexuals to be “society’s greatest menace” and then tasked a police “morals” squad with eliminating it. (Two gay men were shot within weeks of the squad’s creation; hundreds of others were soon arrested or blackmailed by the cops.)

How could Warhol not have been floored by a book that was about as openly queer as any writing of its era could be? Its thirteen-year-old hero, Joel Knox, gets described by Capote as defying mainstream notions “of what a ‘real’ boy should look like…He was too pretty, too delicate and fair-skinned; each of his features was shaped with a sensitive accuracy, and a girlish tenderness softened his eyes.”

He could have been talking about Warhol at that age. “Go on home and cut out paper dolls, sissy-britches,” says a playmate to Joel. That’s just what Warhol had done when a childhood strep infection had left him bedridden with spasms for three summers running.

One pan described the book as “lavender eyewash” and said it was evidence of the disintegration of American culture. For Warhol and certain others, the wounds that such words meant to inflict on Capote came with as much glory as shame: They were the stigmata of that moment in gay culture. Like all such markers of martyrdom, they stand as a sign of some kind of victory over your tormentors.

A contemporary of Warhol and Capote’s remembered how, surrounded in college by “truculent” veterans on the G.I. Bill, the campus aesthetes found each other through Capote’s new book: “To walk with Capote in your grasp was as distinctive, and as dissenting from the world’s values, as a monk’s habit.”

In the twenty-first century, it is almost impossible to fully understand what it meant to be gay in postwar America, when both Warhol and Capote came of age, and came out. Two years after Other Voices appeared, the US Senate produced a report called Employment of Homosexuals and Other Sex Perverts in Government that included, among its other lies and brutalities, the assertion that “one homosexual can pollute a Government office.” The Lavender Scare that followed stole the livelihoods of countless gay Americans. And yet Warhol and Capote dared to build their creative personas, and many of their creations, around limp wrists and levitating loafers.

In an amazing watershed for queer culture, Gore Vidal published a novel of gay life just a week before Capote’s, and it was even more clearly and polemically “out.” But with prose as spare and “muscular” as any straight author’s, the novel comes closer to arguing for the potential normalcy of gay life—for its strong wrists and sensible shoes—than for the virtues of its exceptional culture. Warhol and Capote were almost unique in accepting, and in helping to create, a gay culture and art that could be proudly other. You can feel that in almost every word they utter in Roth’s play; you can also feel how hard-won that acceptance was, even for the two men who did the accepting.

Eighteen months after the appearance of Other Voices Warhol moved to Capote’s New York, where his interest in the writer turned into proper obsession.

For Warhol and certain others, the wounds that such words meant to inflict on Capote came with as much glory as shame.

“I started getting these letters from somebody who called himself Andy Warhol. They were, you know, fan letters,” Capote recalled. “But not answering these Warhol letters didn’t seem to faze him at all. I became Andy’s Shirley Temple. After a while I began getting letters from him every day!” That pretty much squares with all kinds of records that document Warhol’s crush. Capote’s agent wrote to the young artist asking him to stop with the notes but was clearly more amused than distressed by his antics: “[Capote] said he’d been receiving some inane notes from one Warhol and thinks you must be slightly insane. So of course I told him you were.”

For all his annoyance, Capote must have taken a certain pride in having a stalker of his very own, and one who was more than a bit above average, culture-wise. By the summer of 1952, Warhol had already scored his first New York solo show, in a velvet-draped gallery famous for its daring modernism—and for the camp antics of its owner, a former ballet dancer. The exhibition was called Fifteen Drawings Based on the Writings of Truman Capote, and Capote himself was impressed enough by its images to imagine them illustrating new editions of Other Voices.

For most of the 1950s, Warhol and Capote orbited each other at some slight distance—they could be seen dining at the gay-owned and decidedly camp Café Nicholson, if not at the same table then in the same dining room.

The duo got closer in the fall of 1966. That’s when Capote celebrated the success of his blockbuster true-crime novel, In Cold Blood, with a masked ball at the Plaza Hotel, at which Warhol was among the celebrity guests. In the years that had passed since the two men’s first encounters, their status had evened out. If Capote was an undoubted literary star, Warhol had at least equal status in the art world, and beyond, as the madcap capo of New York’s underground scene.

But where Warhol’s fame had liberated him to make art that capitalized on his avowedly gay persona—the film Blow Job was one of his most (in)famous works of that era—the quite “straight” narrative of In Cold Blood followed Vidal’s lead in divorcing Capote’s writing from his persona, which continued to revel in queerness. You have to wonder if the creative gap between Other Voices and In Cold Blood helped stymie Capote’s further growth as an artist—he achieved very little afterward, while Warhol’s output never flagged.

In 1972, Warhol and Capote at last became true friends, after they were brought together by Capote’s pal Lee Radziwill, Jackie Kennedy’s sibling and thus a former “First Sister of the United States.” She was renting the lavish compound that Warhol’s artistic success had allowed him to buy out on the tip of Long Island, where Capote also liked to summer. Before long, Warhol was suggesting to his new friend that the two do some kind of “sisters act.”

Although it doesn’t seem that Capote and Warhol ever had a romance, they went on to function like a classic pair of gay exes—loving but often catty as well, full of knowledge, but also reservations, about each other’s past and behavior. That’s the couple that is so perfectly captured in Roth’s play.

Warhol, unlike Capote, had found a way to reconcile who he was and what he made.

It does seem to reveal a reversal, however, of the roles they’d played in 1948. We come to see Warhol as the model for some kind of successful integration into the wider culture. Capote seems more at sea.

That could be because Warhol, unlike Capote, had found a way to reconcile who he was and what he made. He had used the automatic outsider status he had always had as a gay man to power the most avant-garde art he could imagine, which by definition had to be far out of the mainstream. Even when he seemed to be courting the center, he was almost always busy working the margins. Capote, on the other hand, had never managed that kind of reconciliation. His most successful creations—not so much Other Voices as Breakfast at Tiffany’s and In Cold Blood—spoke directly and easily to a mass audience and were meant to.

In Roth’s true-life play—a parallel, in some ways, to Capote’s true-crime novel—you get the sense that Capote is frustrated by conflicting desires: to be truly accepted deep into the mainstream while also preserving his gay outsiderism. But that didn’t become an option in American culture until well after he’d been felled by the drugs and booze that his terminal angst forced on him. Whereas Roth’s Warhol comes across as having a certain emotional ease that actually foreshadowed—because it helped cause—the hard-won ease of gay culture in the twenty-first century.

“I just assume everything is going to turn out for the worst and if it doesn’t that’s just so much gravy,” Capote says to Warhol toward the middle of the play. “I mean, my life is so beleaguered and your life is so un-beleaguered.”

And then, at its end: “When God does give one a gift, whatever it may be, composing or writing, for whatever pleasure it may bring, it also is a very painful thing to live with. It’s a very excruciating life.”

*

MARILYN/VISIT ME

(pgs. 34-37)

ANDY

You know the plot next to Marilyn in Forest Lawn

is available for $25,000.

TRUMAN

Let’s buy it, and they can put us all together.

ANDY

We can be famous. We can share it. It will be 12

and a half, okay, and we can be cremated. You can

have one half section, okay?

TRUMAN

Marilyn Monroe was somebody I knew real well over

a 10-year period. And I was very, very fond of

Marilyn. But I really fixed old Marilyn once.

ANDY

Why? What did—

TRUMAN

Well, she was really awfully dependent on me at

a certain point in her life when she was in New

York. I really liked her a lot, we had lunch all

the time. Well, she was—I always figured she

would be late, you know. But one day she was—we

were supposed to meet at 1:15 and it was getting

to 2:00. And I just got up and I left. And I left

a little note for her and it said, “stop playing

Marilyn Monroe or else forget me. Yours truly,

T.C.” And she calls me up she says, “I’m in floods

of tears.” I says, “you don’t sound like it.”

ANDY

Wow.

TRUMAN

But of course, her thing of being late was just

completely neurotic. There are people who are just

neurotic about being late. I’m always on time.

Always exactly on the dot.

ANDY

Always.

(Pause. TRUMAN finishes HIS drink.)

TRUMAN

My doctor suggested that I adopt some healthier

hobby other than wine-tasting and fornication. So

I’m going to get all pulled together. You can come

out and visit me at the center.

ANDY

Okay, all right. I’ll come out and visit you. That

would be really great. Oh, Truman, we’re going to

miss you.

TRUMAN

And if luck allows and discipline holds, I will

have time to arrive at higher altitudes, where the

air is thin but the view exhilarating.

ANDY

It is one plane ride, and then you can take a car?

TRUMAN

Yes. It is not a big trip at all. I’m getting

ready to have a last sensational thirty years.

(Pause.)

Andy, would you call me up?

ANDY

Oh, sure, yeah.

TRUMAN

I mean, would you, really?

ANDY

Yeah.

TRUMAN

You see, I might call you, but I didn’t think

you’d call me.

ANDY

Oh, yes, I would.

TRUMAN

You would?

ANDY

Yeah.

TRUMAN

I wondered.

(Pause.)

(The lights change.)

__________________________________

Excerpted from WARHOLCAPOTE: A Non-Fiction Invention by Rob Roth. Introduction by Blake Gopnik. Copyright © 2022. Available from Simon & Schuster.

Blake Gopnik and Rob Roth

Blake Gopnik is an American art critic who has lived in New York City since 2011. He previously spent a decade as chief art critic of The Washington Post, prior to which he was an arts editor and critic in Canada.

Rob Roth was nominated for a Tony Award as Best Director for his Broadway debut, Beauty and the Beast, which became one of the top ten longest-running musicals in Broadway history. The show has been seen by over 40 million people all over the world, winning the Olivier Award for Best Musical in London. Rob went on to direct the world premiere of Elaborate Lives: The Legend of Aida, collaborating with Sir Elton John and Sir Tim Rice. Rob directed the Broadway musical Lestat, based on the Anne Rice Vampire Chronicles with a score by Elton John and Bernie Taupin. Rob frequently directs rock concerts, collaborating with legendary artists including KISS, Alice Cooper, Dresden Dolls, Cyndi Lauper, and guitar legend Steve Miller. Rob is an avid collector of rock and roll graphics, and his collection is showcased in the coffee table book The Art of Classic Rock. Rob and his husband Patrick live in New York City with their labrador retriever Tag.