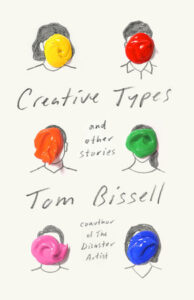

How to Write (Almost) Anything: A Very Serious Guide by Tom Bissell

“Even when you are not ‘working on the book,’ you are working on the book.”

When I was starting out, the various lists concocted to announce America’s best young fiction writers meant a lot to me. Being included on such lists, I mean. The New Yorker has its 20 Under 40, Grantahas its Best Young American Novelists, the New York Public Library has its Young Lions Fiction Awards. After every coronation, I was secretly crushed not to be included, even after it was pointed out to me that you more or less had to be a novelist—or at least primarily a fiction writer—to be considered. I haven’t been “primarily a fiction writer” since I was an unpublished twenty-five-year-old, but that somehow didn’t matter. I wanted to be judged good enough to be the exception. And that, children, is how young writers Pavlov themselves into caring about the wrong things.

I’ll never begrudge anyone that cares about prizes and accolades, because if you get them they can change your life. But they also don’t really do anything to make the hard part of writing easier. If anything, they make the hard part of writing harder. I was in my mid-thirties by the time my private hunger for recognition faded away, which was akin to draining a blister. Suddenly I could walk through the world without acutely feeling every step. Don’t misunderstand: I still get a camera flash of irritation when I’m not a finalist for the National Book Award, even during years I haven’t published a book. The difference is I laugh about my irritation now, not enthrone it.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that my career options multiplied in the wake of this internal letting go. I began writing as an aspiring novelist who occasionally wrote short stories, but I began publishing as a nonfiction writer who moonlighted as a novelist and occasionally wrote short stories. The novels never happened for me—I’ve written four unpublished novels and started half a dozen others over the years—but the short stories kept coming. So did a bunch of other things: nonfiction books about war and cult movies and Christianity, magazine reporting, political punditry, literarycriticism, scriptwriting for blockbuster video games, and lately television writing. I never became the writer I once longed to be. I became something that now seems possibly more interesting: a writer I could have never imagined being.

It’s come at a cost, though, one of them being experiential coherence. When I’m talking to video-game people, I’m often asked what writing for television is like. When I’m talking to book people, I’m often asked what writing a video game is like (and why anyone would want to). When I’m talking to television people, I’m often asked if I regret the years I wasted writing books and video games.

“Write proposal for publisher. Sneakily imply throughout that this is it—your breakthrough title.”Here, then, is a primer that attempts to enumerate the highlights of writing across different mediums and genres.

*

The Magazine Piece

Score assignment. Procure research books on subject you’re writing about. Read almost half of them.

Do reporting. Visualize piece in your mind while reporting. It will be long, thoughtful, discursive (but not too!), and definitive. Longform will link to it. It will be glorious.

Start writing. Not glorious. Nothing about this is glorious. When stuck, create multiple graphs and flowcharts to illustrate how scene work, reporting notes, and research notes will crosshatch and enrich one another.

Frown as they do not crosshatch and enrich one another

Finish 19,000-word draft. Check contract. Note that it calls for 5,000 words.

Finish editing for length. Draft is now 23,000 words.

Editor suggests random paragraph from middle of now-12,000-word piece is “where the real story starts.” Scoff because you exerted almost no effort “writing” said paragraph.

Gasp upon realization she is absolutely correct.

Exhale when finished piece finally scheduled for publication.

Suddenly remember your fellow citizens have elected lurid headline-generating golem as president. Fret as piece is delayed, delayed, and delayed again.

Piece published several months later. Get asked to discuss piece on Dallas Public Radio. Gratefully agree, realizing day before interview you’ve forgotten everything you once knew about subject. Panic.

*

The Narrative Nonfiction Book

Write proposal for publisher. Sneakily imply throughout that this is it—your breakthrough title.

Procure research books on subject you’re writing about. One of them is identical to, and better than, book you planned to write.

Write new proposal for publisher.

Begin new book with firm ideas about where you’re going, what you’re doing.

Conclude, after six months, “There’s no book here.”

Realize, four minutes later, you’ve already spent advance.

Return to work on book. Accept that “working on the book” is now your default position. Even when you are not “working on the book,” you are working on the book. The only times you are not “working on the book” is when you have carved out actual time to work on the book because it is during such time that you realize you hate the book and will do literally anything to avoid working on it.

Finish book. Marvel at publisher’s ambitious marketing plan.

Briefly contemplate suicide when bad review in New York Times prompts publisher to “reassess” ambitious marketing plan.

Come across remaindered copy of book years later in used bookstore. Somehow find yourself thinking, “I should write another book.”

*

The Video Game

Imagine process will be grand adventure. Imagine yourself as twenty-first-century F. Scott Fitzgerald in new, digital Hollywood.

Conveniently forget what happened to F. Scott Fitzgerald in old, analog Hollywood.

Prior to entering game industry, write book about video games that argues “better storytelling” will save and redeem benighted medium.

Spend next decade bursting into laughter when reminded of book’s thesis.

While in pre-production, write detailed story summaries and character descriptions intended to guide artists and level designers throughout production cycle.

Near end of production cycle, feign surprise when artists and level designers admit they never read your detailed story summaries or character descriptions.

At some point, idly add up total word count for every story summary, character description, cinematic scene, level script, multiplayer script, and collectible script you have written over previous two and half years. Plunge face into hands when word-count total surpasses that of every book you’ve published combined.

Find yourself passionately arguing with another human adult why a monster’s rocket launcher should be gold rather than black.

Assure puzzle designer that line of dialogue you’ve written to indicate solution to her puzzle is “totally adequate” and “only a moron” would fail to grasp solution.

Sit next to puzzle designer during gameplay test and watch as fifteen consecutive players fail to solve puzzle.

Tell your colleagues, “I love working in animation! You can change stuff until the last minute!”

Tell same colleagues, months later, “I hate working in animation! You can change stuff until the last minute!”

Calmly nod while game director explains to you why scene that explains game’s story has been cut. Also why player’s companion character is no longer a woman but a robot.

Work five eighty-hour weeks in a row. Discover swiftest way to jump line in Cedars-Sinai critical care unit is to stroll in complaining of chest pain.

*

The Television Show

Get network production commitment on pilot script. During notes call, take to heart network directive to “Go nuts!” and “Have fun!” and “Don’t worry about production details!”

Having gone nuts, having had fun, having not worried about production details, calmly nod while network executives explain shortly before shoot why pilot’s budget has been slashed.

Resist network suggestion to include car chase at top of pilot to “hook viewers.” Eventually cave and write car chase.

Go for long walk when informed how much car chase will cost to shoot.

Write long, enflamed emails about necessity of cutting car chase. Enumerate other, cheaper scenes that could replace car chase.

Wind up shooting car chase.

Resist urge to shout when network reveals screentest data indicating widespread audience indifference to car chase.

Briefly contemplate suicide when pilot does not receive series order.

Get big-name director to attach to different television project. Spend half a decade “finalizing deal.”

Discover management team feels no impetus to “finalize deal” because they know big-name director will never actually commit to said television project. What big-name director’s attachment gets you is meetings with big-name producers.

Think to self, “That makes sense.” Recoil in horror. You have become what you hate.

*

The Short Story

Sit down, crack knuckles.

Check notes. Realize: No notes.

Ponder plan. Realize: No plan.

Begin to write. Feel vaguely familiar glow envelop you. Which is, you realize, actual creative joy.

Accept you will not be paid tens of thousands of dollars for short story. Accept it will not have an audience measured in millions. Accept it will not be hotly debated on internet forums. Welcome possibility it will be an infinitesimally small thing. Understand that this is what makes it pure.

Complete draft of story. Print out manuscript and repair, pencil in hand, to sunlit patio to read.

Stop making notes halfway through. Story hideous, unsalvageable.

Open email. Start asking around for TV and game-writing gigs.

__________________________________

Creative Types by Tom Bissell is available via Pantheon.