How to Visit the Graves of 75 Famous Writers

From crypts to hillsides to the Schomburg Center

It’s nice to visit the grave of a favorite departed writer. Graveyards, in general, are peaceful places—good for writing, and for thinking about writing—and of course there is a long history of people making pilgrimages to the last resting places of those they loved, either in person or on paper. Of course, not every author has a grave, as such. Maya Angelou’s ashes were scattered, as were Djuna Barnes’s—the latter on Storm King Mountain, before a dogwood grove was planted on the spot in her honor. Apparently Shirley Jackson’s son has hers. Kurt Vonnegut’s grave is in a secret location. Some are private, like Chinua Achebe’s—he is buried in a mausoleum on his private family compound. But others are available to visit, for the curious, morbid, and devoted. Below, a guide to the graves of 75 famous writers, at home and abroad.

Photo via Findery

Photo via Findery

Sylvia Plath (1932-1963)

St Thomas A. Beckett Churchyard, Heptonstall, West Yorkshire, England

What to know: Plath’s gravestone has been repeatedly vandalized—first fans erased the “Hughes” from her name (at least three times), then the gravestone went missing, then “masculinists” erased the “Plath” from her name. Presumably it’s back in order now. [Edit: apparently the whole masculinists thing was an April Fool’s joke—obviously, I fell for it. The best jokes are the totally believable ones!]

*

Photo via SmarterParis

Photo via SmarterParis

Oscar Wilde (1854-1900)

Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, France

What to know: Wilde’s tomb has also been the victim of vandalization—though of a much more loving sort. In years past, the stone was covered in red lipstick kisses, left by Wilde’s admirers. But in 2011, his descendants, fearing degradation from the lipstick, had the memorial cleaned and protected behind glass. “We are not saying, ‘Go away,’ but rather, ‘Try to behave sensibly,’” Wilde’s grandson told the New York Times. Predictably, the glass is now usually covered in lipstick too.

*

Photo by Lorenzo Brieba

Photo by Lorenzo Brieba

James Baldwin (1924-1987)

Ferncliff Cemetery and Mausoleum, Hartsdale, New York. Hillcrest A, Grave 1203

What to know: Baldwin, who died of stomach cancer, is buried alongside his mother, Emma Berdis Jones, who outlived him by twelve years.

*

Vladimir Nabokov (1899-1977)

Cimetière de Clarens-Montreux, Montreux, District de la Riviera-Pays-d’Enhaut, Vaud, Switzerland

What to know: He is (of course) buried next to his wife Véra, to whom he dedicated almost all of his books, and who was “his first reader, his agent, his typist, his archivist, his translator, his dresser, his money manager, his mouthpiece, his muse, his teaching assistant, his driver, his bodyguard (she carried a pistol in her handbag), the mother of his child, and, after he died, the implacable guardian of his legacy.”

*

Photo via Pinterest

Photo via Pinterest

Virginia Woolf (1882-1941)

Monk’s House garden, Rodmell, Lewes District, East Sussex, England

What to know: Virginia Woolf committed suicide by filling her pockets with stones and walking into the River Ouse. She was cremated, and her ashes are buried beneath an elm tree in the garden of Monk’s House, the 18th-century cottage where she lived with her husband, Leonard Woolf, from 1919 until her death. When Leonard Woolf died of a stroke, 50 years later, he too was cremated, and his ashes buried with his wife’s. The elm has since blown down, and busts of the Woolfs were erected in the garden in its place.

*

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Susan Sontag (1933-2004)

Cimetière de Montparnasse, Paris, France; Division 2, Section 2, 1 East, 28 North, concession number 3PA2005

What to know: Sontag died after a long battle with myelodysplastic syndrome, which developed into leukemia. In his memoir, Swimming in a Sea of Death, Sontag’s son David Rieff wrote:

My decision to bury my mother in Montparnasse had little to do with either literature or even with her lifelong love of Paris, rapturous as it was. The decision was mine alone—that much her will had stipulated—and I had to bury her somewhere—she had a horror of cremation. But since she believed to the end that she was going to survive her cancer, and therefore had seen no reason to leave any specific instructions or even to express any wishes on the matter, I had no idea what those wishes might have been. We had no ceremonies of goodbye, to use Beauvoir’s great phrase. And without her voice to guide me, I had nothing to go on. It was as if she had died suddenly, in a car accident or a plane crash, rather than slowly, incrementally, horribly of MDS. . . So I improvised, all the while wondering, as I still wonder, if I was doing the right thing.

The cemeteries of New York are ugly, and the particular one where her own father is buried is one of the ugliest of all of them. Besides, my mother had not known of it until very late in her life and, as far as I know, only visited it once, even if her father figured repeatedly in the inwardly directed talk of her final days—talk that seemed to carom freely between lament, settling of accounts, and personal history. And I knew that my mother felt no particular connection to the other American cities—Tuscon, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Boston—in which she had lived. That left Paris, for so long her second home. Or so I reasoned, to the extent that I was capable of reason in the immediate aftermath of my mother’s death. In any case, Paris was also a second home to many of my mother’s friends, and as far as I can see, graves are for the living if they are for anything at all.

And so I had my mother’s body shipped from Kennedy Airport in New York to Paris aboard the same Air France evening flight she had taken literally hundreds of times during her life. it was our last trip together. I remember thinking, “I am taking my mother to Paris for the last time.” . . . [In the Volvo hearse] I took my mother on one last, sweeping ride through Paris, and then I buried her.

*

Photo via Vanita

Photo via Vanita

Octavia Butler (1947-2006)

Mountain View Cemetery and Mausoleum, Altadena, California, USA, Grave 6 Lot 4517 Eagles View

What to know: The gravestone is engraved with a quote from Parable of the Sower: “All that you touch, you change. All that you change, Changes you. The only lasting truth is Change. God is Change.” This is the basis of the Earthseed religion, which Butler invented in her novels.

*

Photo via David Rosser

Photo via David Rosser

Dylan Thomas (1914-1953)

In the over-spill graveyard of Saint Martin’s Church, Laugharne, Carmarthenshire, Wales

What to know: As the legend goes, Dylan Thomas collapsed in New York’s famous Chelsea Hotel shortly after declaring, “I’ve had eighteen straight whiskies. I think that’s the record!” He died in the hospital a few days later and has gone down in history as the ultimate example of a poet who drank himself to death—but newer research has suggested that undiagnosed pneumonia might have been the real culprit. Not that the binge drinking helped or anything. Dylan Thomas’s wife, Caitlin Thomas, is buried in the same grave; her name appears on the other side of the cross. She outlived him by over 40 years.

*

Photo via Weekend Wanderluster

Photo via Weekend Wanderluster

Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961)

Ketchum Cemetery, Ketchum, Idaho, USA

What to know: According to Leicester Hemingway’s My Brother, Ernest Hemingway, Hemingway’s grave is next to that of his “old hunting friend” Taylor Williams, aka “Beartracks,” who died two years before him. “Plots in the cemetery at Ketchum are twenty-five dollars each,” Leicester wrote, “so the Hemingway family bought six. Ernest always liked space.” An altar boy fainted during the ceremony, knocking into “the large cross of white flowers at the grave’s upper end,” which was now “wildly askew. . . No one touched it during the remainder of the ceremony. It seemed to me that Ernest would have approved of it all.” A Basque shepherd is buried at the foot of Ernest’s grave. Fans who visit frequently leave “coins, flowers, and half-drunk bottles of alcohol” as tributes to Papa.

*

Photo by Woolmark

Photo by Woolmark

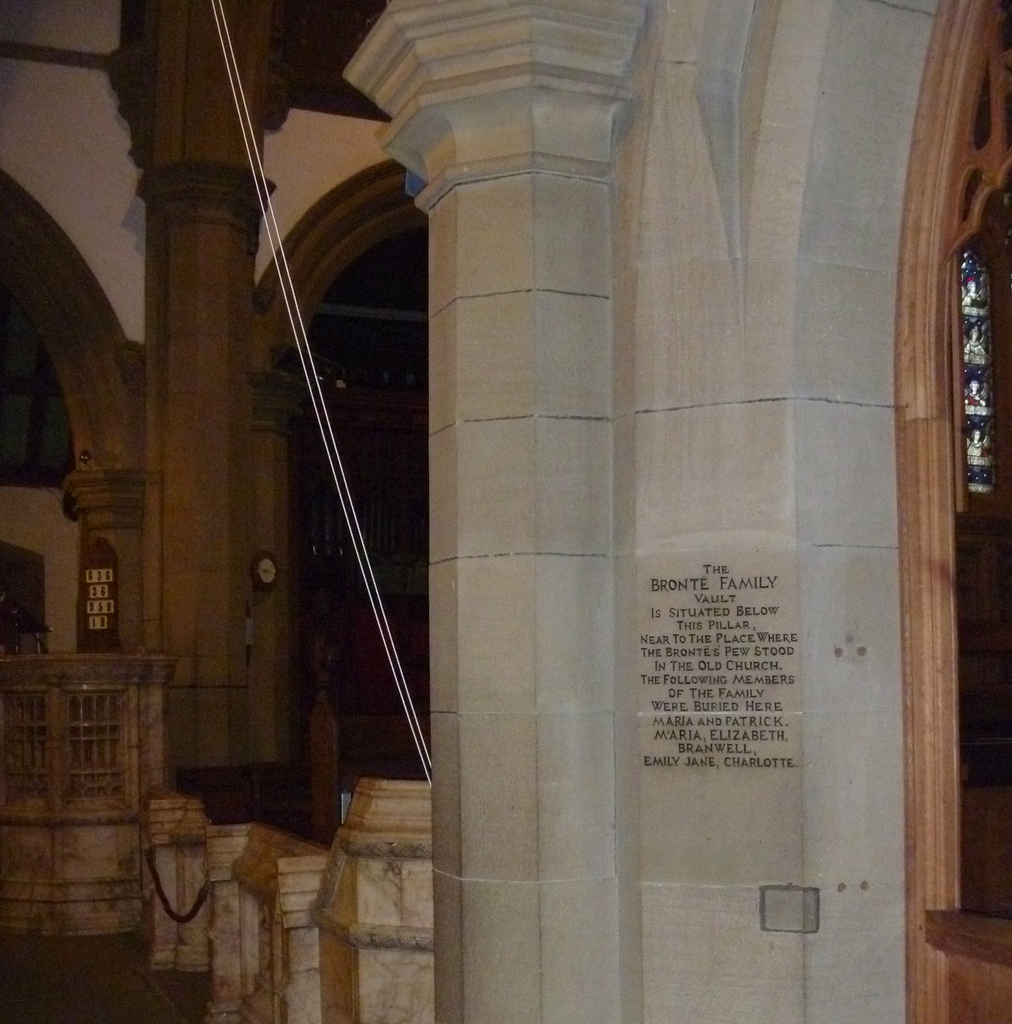

The Brontë sisters, Charlotte (1816–1855), Emily (1818–1848), and Anne (1820–1849)

The Brontë family vault, at St Michael and All Angels’ church, Haworth, Metropolitan Borough of Bradford, West Yorkshire; and in St Mary’s Churchyard, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, England

What to know: Charlotte and Emily were buried with the rest of their family near where their regular pew was in the church where their father was curate (it has since been torn down and rebuilt). It was, apparently, Charlotte’s decision to bury Anne in the town where she died; but her gravestone was so riddled with errors that it had to be refaced once, and then replaced entirely.

*

Photo via Pinterest

Photo via Pinterest

Franz Kafka (1883-1924)

New Jewish Cemetery, Prague, Czech Republic (according to Find-A-Grave: “Enter through the main gate and walk to the right side of the ceremonial hall within. There you will find a sign pointing to Kafka’s grave. Follow the direction of the sign until you reach the sector 21 sign. Turn right at this sign and head towards the wall. Turn left when you get to the wall and walk until you reach the end of the sector (also marked by a sign). Kafka’s grave is next to the sign, facing the wall.)

What to know: The Cubist gravestone was designed by Bohemian architect Leopold Ehrmann.

*

Photo via Palm Beach Post

Photo via Palm Beach Post

Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960)

Garden of Heavenly Rest, Fort Pierce, Florida, USA

What to know: When Zora Neale Hurston died in 1960, her neighbors took up a collection for her funeral—but didn’t have enough for a headstone. Her grave sat unmarked until Alice Walker went looking for it in 1973, eventually tracing her to Fort Pierce, to a neglected and unused cemetery. She is told that there’s a circle, and that Hurston’s grave is in its center, but as she writes in her famous essay “Looking for Zora,” “the ‘circle’ is over an acre large and looks more like an abandoned field. Tall weeds choke the dirt road and scrape against the sides of the car. . . this neglect is staggering. As far as I can see there is nothing but bushes and weeds, some as tall as my waist.” Eventually she finds it, and soon thereafter she has a headstone made. It read:

ZORA NEALE HURSTON

“A GENIUS OF THE SOUTH”

NOVELIST FOLKLORIST

ANTHROPOLOGIST

1901 1960

The phrase “A genius of the South,” Walker writes in her essay, is from a Jean Toomer poem.

*

Photo via Chosley.info

Photo via Chosley.info

Agatha Christie (1890-1976)

St Mary’s Churchyard, Northwest corner, Cholsey, Oxfordshire, England

What to know: Christie is buried with her husband, the archaeologist Sir Max Mallowan. It’s fairer to say he was buried with her, of course—his second wife, whom he married a year after Christie’s death and a year before his own, rests elsewhere. The man in the photograph is named Marek Borkowski, “renowed Polish conservationist and wildlife champion,” and is included for scale.

*

Photo via Mike Culpepper

Photo via Mike Culpepper

Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986)

Cimetière de Pleinpalais, Geneva, Switzerland

What to know: The headstone inscription is in Anglo Saxon, which he taught at the National Library in Buenos Aires (he met his wife in class). It is from the Old English poem Battle of Maldon, and translates to “do not fear at all.” Colm Tóibín wrote of Borges’s burial:

He is buried close to John Calvin in the Cimetière de Pleinpalais, also known as the Cemetery of the Kings, close to the old city in Geneva. It is a calm, unostentatious cemetery, with single graves mostly of famous people, the very opposite in tone to the Recoleta in Buenos Aires in which baroque and gothic-windowed family vaults do battle with the rococo and the overadorned. Borges’s gravestone was clearly designed by [Maria, his wife] Kodama with references and images which mattered to them both in their relationship. In death, his grave did not make him an Argentine hero, but rather the husband of a woman he had loved for the last decade or more of his life.

In 2011, Chilean writer Eduardo Labarca provoked outrage when he published a book, El enigma de los módulos, whose cover depicted Labarca urinating on Borges’s grave (he was actually holding a water bottle). Labarca defended himself to the Guardian, saying “Peeing on that tomb was a legitimate artistic act. The cover of the book is coherent with the contents and is best understood through that. . . I am not just a person who goes around peeing on tombs, but a writer with a serious oeuvre. . . Anyone who is offended by this is very short-sighted. . . Borges was a giant as a writer but I feel complete contempt for him as a citizen. As an old man, almost blind, he came to meet the dictator Pinochet in the days when he was busy killing.”

*

Photo via Tolkien Library

Photo via Tolkien Library

J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1973)

Wolvercote Cemetery, Oxford, Oxfordshire, England

What to know: Tolkien is buried with his wife, Edith Mary Tolkien, who predeceased him by two years. He’d been in love with her since he was sixteen years old, but his guardian forbade him from courting or even contacting her until his 21st birthday (you see, she was a Protestant, and older by three years). On Tolkien’s 21st birthday, he proposed. Edith was already engaged to someone else (she hadn’t heard from him in some time), but it didn’t take her long to break it off and accept (and convert to Catholicism). In 1917, after surviving the Battle of the Somne, Tolkien began to write about Beren and Lúthien, two star-crossed lovers (one man, one Elf-maiden) inspired by himself and his wife. Their names now adorn Tolkien’s grave.

Photo via Edith Wharton Society

Photo via Edith Wharton Society

Edith Wharton (1862-1937)

Cimetière des Gonards, Versailles, Departement des Yvelines, France

What to know: Wharton is buried three graves away from her mysterious long-time friend Walter Berry, whom she called “the great love of all my life.” Her other loves, alas, remain at The Mount.

*

Photos by Sidharth Singh

Photos by Sidharth Singh

Patricia Highsmith (1921-1995)

Cimitero di Tegna, Tegna, Switzerland

What to know: Highsmith was cremated after her death; of the ceremony, biographer Andrew Wilson wrote:

Her friends chose a simple white blouse for her from which the lace had been removed. A dozen mourners gathered at the hospital in the mortuary room where Pat lay in an open casket, before driving to the cemetery in Bellinzona. There, Highsmith’s friends followed the funeral car on foot as it made its way slowly to the crematorium. ‘It was a cold day and sad, but also very simple and I remember thinking Pat would have been pleased by this and pleased by the small number of mourners, all people who had known and loved her,’ says Vivien De Bernardi, who spoke briefly at the service. ‘I felt it was exactly the way Pat would have wanted it.'”

*

Photo via Pierre-Yves Beaudouin

Photo via Pierre-Yves Beaudouin

Richard Wright (1908-1960)

Cimetière du Père Lachaise, Paris, France, Division 87 (columbarium), urn 848

What to know: After his death, Richard Wright was cremated with a copy of his memoir, Black Boy. His urn is interred here.

*

Photo by Clive Baugh

Photo by Clive Baugh

James Joyce (1882-1941)

Friedhof Fluntern, Zürich, Switzerland, Familiengräber, 80398

What to know: Yes, it’s true: the ur-Irish writer is buried in Switzerland. Joyce died in Zurich in 1941 unexpectedly, after undergoing surgery for a perforated ulcer. He was buried there; according to biographer Richard Ellmann, “A green wreath at the funeral had a lyre woven in it as emblem of Ireland. Otherwise Ireland had no part in the funeral.” Nora offered the repatriation of Joyce’s remains, but the Irish government turned her down. Famously, when Joyce’s daughter Lucia was informed of her father’s death, she said: “What is he doing under the ground, that idiot? When will he decide to come out? He’s watching us all the time.”

Joyce was originally buried in a normal grave; it was in 1966 (on Bloomsday, naturally) that the cemetery unveiled the bronze, life-size statue of Joyce, which had been created by sculptor Milton Hebald. Joyce now rests with his beloved Nora Barnacle, as well as their son George Joyce and his wife, Asta Osterwalder.

*

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

William Butler Yeats (1865-1939)

Drumcliff Churchyard, Drumcliffe, County Sligo, Ireland

What to know: Yeats’s epitaph is from the last stanza of his poem “Under Ben Bulben,” one of the last poems he ever wrote. His other apparent wishes for his burial (Drumcliff, “no marble, no conventional phrase”) have also been carried out.

Under bare Ben Bulben’s head

In Drumcliff churchyard Yeats is laid,

An ancestor was rector there

Long years ago; a church stands near,

By the road an ancient Cross.

No marble, no conventional phrase,

On limestone quarried near the spot

By his command these words are cut:

Cast a cold eye

On life, on death.

Horseman, pass by!

However, as it turns out, Yeats isn’t actually buried in Yeats’s grave. He died in France on the eve of WWII, and his widow couldn’t get his remains repatriated until 1948. That’s in part because no one had them. Yeats’s friends knew that his ashes had been scattered two years before, and at his interment, poet Louis MacNeice grumbled that Yeats’s coffin was probably only a very fancy burial for “a Frenchman with a club foot.” Indeed, papers discovered a few years ago show that the diplomat tasked with returning Yeats’s remains asked a pathologist “to reconstitute a skeleton presenting all the characteristics of the deceased.” Seems like maybe he should have specified in a poem that he actually be in his own grave.

*

Photo via The Snout

Photo via The Snout

Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964)

Memory Hill Cemetery, Milledgeville, Georgia, USA

What to know: Flannery O’Connor died of lupus in 1964 in the Baldwin County Hospital. She is buried next to her father.

*

Photo by Cam Self

Photo by Cam Self

W.G. Sebald (1944-2001)

St Andrew’s Churchyard, Framingham Earl, Norfolk, England

What to know: Teju Cole has described visiting Sebald’s grave beautifully in the New Yorker:

It was a quiet, shaded lane. The fog had lifted, but the day was not bright. There was not a soul around. I raised the slim iron latch of the wooden gate, which was overgrown with creepers, and went around the old Norman church with its characteristic East Anglian round tower. Round-tower churches are rare in England now, except in Norfolk and Suffolk. St. Andrew’s is built of honey-colored stone, its churchyard full of old stones, old graves, well-kept but arranged somewhat haphazardly. Flowers were in bloom all over, and there was in particular a profusion of foxgloves.

I searched. Finally, coming around the chancel, I saw S.’s gravestone: a slab of dark marble, a slender marker shaded by a large green bush. There he is, I thought. The teacher I never knew, the friend I met only posthumously. Some water had trickled down the face of the slab, making the “S” of his name temporarily invisible, as well as the second “4” in 1944 and the “1” in 2001. The erasures put him into a peculiar timelessness. Along the top of the gravestone was a row of smooth small stones in different shades of brown and gray. There was a little space on the left. I picked up a stone from the ground and added it to the row. Then I knelt down.

How long was I there?

*

Photo by Ken Jellema

Photo by Ken Jellema

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917-2000)

Lincoln Cemetery, Blue Island, Cook County, Illinois, USA, Sect. TLA, Lot 97, S3-E 1/2

What to know: Her grave is in the shape of the book: on the front, her photo and essential details; on the back, her selected works; on the spine, some of her best.

*

Photo via The Leidener

Photo via The Leidener

Marguerite Duras (1914-1996)

Cimetière de Montparnasse, Paris, France, Division 21

What to know: This photo doesn’t show it, but much the same way that fans would kiss Oscar Wilde’s grave, fans of Duras often pay tribute to her by sticking pens and pencils into the flowerpot that rests at the head of the stone.

*

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Yukio Mishima (1925-1970)

Tama Cemetery, Fuchū, Tokyo, Japan

What to know: Mishima famously committed ritual suicide after failing to inspire a coup d’état to restore the Japanese Emperor to power in 1970. As rumor has it, yakuza and right-wing visitors often leave flowers and alcohol at Mishima’s grave in the middle of the night—perhaps that’s why the cemetery officials won’t publicly admit it’s even there.

*

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) and Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986)

Cimetière de Montparnasse, Paris, France, Division 20

What to know: “The comradeship that welded our lives together made a superfluous mockery of any other bond we might have forged for ourselves,” de Beauvoir wrote. “At times this meant that we had to follow diverse paths—though without concealing even the least of our discoveries from one another. When we were together we bent our wills so firmly to the requirements of this common task that even at the moment of parting we still thought as one. That which bound us freed us; and in this freedom we found ourselves bound as closely as possible.” In life, Sartre and de Beauvoir had perhaps the most famous open relationship in literary history; in death, their bond is about as close (and as closed) as you can get.

*

Photo via Curbed

Photo via Curbed

Langston Hughes (1902-1967)

The Schomburg Center, New York, NY USA

What to know: Langston Hughes’s ashes are buried “in a stainless steel book-like vessel” underneath the floor of the Arthur Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, New York. The spot is marked by Rivers, a cosmogram created by Houston Conwill in honor of Langston Hughes and Arturo A. Schomburg, and inspired by Hughes’s poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” fragments of which appear throughout. The life lines of the cosmogram represent the lives of Hughes and Schomburg—beginning in Missouri and Puerto Rico, respectively, and meeting in Harlem.

*

Photo by Jess Bergman

Photo by Jess Bergman

George Eliot (1819-1880)

Highgate Cemetery, London, United Kingdom

What to know: Eliot had wanted to be buried at Westminster Abbey—with the other great writers—but ultimately she was considered “too controversial,” being an atheist who lived with a married man, George Henry Lewes, for 24 years. In the end she was buried beside him in Highgate.

*

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Herman Melville (1819-1891)

Woodlawn Cemetery, New York City, NY, USA, Catalpa Plot, Section 23

What to know: That blank scroll sure is cheeky, considering. I assume the offering of salt in the above photo is meant to make him feel closer to the sea.

*

Photo via Pinterest

Photo via Pinterest

Dorothy Parker (1883-1967)

Dorothy Parker Memorial Garden, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Headquarters, Baltimore, MD

What to know: How did Dorothy Parker wind up in Baltimore—and at the NAACP, no less? As it turns out, in her will, she bequeathed her entire estate to Martin Luther King Jr.; they had never met, and when she died, he was surprised to find himself her heir. But there was another stipulation: should anything happen to King, her will specified, her estate should go to the NAACP. When King was assassinated less than a year after Parker’s death, that’s exactly what happened. She was cremated; her ashes are in an urn in the center of a brick circle (meant to symbolize the Algonquin round table) and directly underneath the above plaque, which includes her suggested epitaph: “Excuse my dust.”

*

Photo via Bourgeois Surrender Vacation Blog

Photo via Bourgeois Surrender Vacation Blog

Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

West Cemetery, Amherst, MA, USA, Lot 53, Grave B

What to know: Dickinson is buried with her sister Lavinia, whom we have to thank for her current ubiquity, as well as her parents and paternal grandparents.

*

Photo by Bernice L. McFadden

Photo by Bernice L. McFadden

Nella Larsen (1891-1964)

Garden of Memory, Cypress Hill Cemetery, Brooklyn, NY, USA

What to know: Like Zora Neale Hurston, Larsen’s grave was discovered and marked for the first time by another novelist who cared deeply about her work. In this case, the living novelist is Heidi W. Durrow, who deeply identified with Larsen, and whose essay about her experience finding and marking Larsen’s grave is well worth reading.

*

Photo via AP

Photo via AP

Pablo Neruda (1904-1973)

Isla Negra, Santiago, Chile

What to know: Neruda is buried next to his wife, Matilde Urrutia, in the garden of his home, now known as Casa de Isla Negra, one of three houses Neruda kept in Chile. It looks idyllic—the view is incredible—but his rest was interrupted a few years ago when rumors that the poet was poisoned caused a judge to order that his body be exhumed and tested—perhaps with cause, as “unusual” bacteria were discovered. His remains are still being tested, so you may want to postpone your pilgrimage until he’s actually in there.

*

Photo by Sean McKim

Photo by Sean McKim

F. Scott Fitzgerald (1895-1940) and Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald (1900-1948)

Old Saint Mary’s Catholic Church Cemetery, Rockville, Maryland, USA

What to know: When F. Scott Fitzgerald died, Zelda tried to have him buried in the Fitzgerald family plot, in St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Rockville. The church, despite Fitz’s fame, balked, arguing that because “had not gone to confession and taken communion regularly, he was unfit to be buried in consecrated ground.” So Zelda stuck him in a grave about a mile away, at Rockville Cemetery. She bought a single plot—so when she died, eight years later, she had to be buried on top of him (they took out his casket, made the hole deeper, then put both back in), which honestly, after how he squashed her career, serves him right. In 1975, their daughter Scottie had her parents moved to the family plot at St. Mary’s, where they were meant to be all along—but she kept their sleeping arrangement as it was, with Zelda on top. Though I wonder if she has any complaints about the famous line from The Great Gatsby cut into the slab.

*

Photo by Michael Schreiber

Photo by Michael Schreiber

Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880)

Rouen Cemetery, Rouen, Haute-Normandie, France

What to know: In The Art of Fiction James Salter describes visiting Flaubert’s grave (he also visited and loved Willa Cather’s): “It was a pilgrimage, I suppose—I’ve made a number of them, not so much in homage as simply to be there and think. . . Flabert’s grave is modest; it is virtually hidden away among others, a stone with nothing more inscribed on it than Here lies Gustave Flaubert, born in Rouen, and the dates. His true monument, of course, is everywhere.”

*

Photo via Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Photo via Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

August Wilson (1945-2005)

Greenwood Cemetery, Sharpsburg, Pennsylvania, USA, Section 7, Row 25, Grave 10

What to know: On the back of the headstone is a message from Wilson’s widow, Constanza Romero: “Augusto, Siempre Te Amaré Constanza.”

*

Photo by Martin Goodman

Photo by Martin Goodman

Douglas Adams (1952-2001)

Highgate Cemetery, London, England, Square 74, Plot 52377

What to know: Visitors to Douglas Adams’s grave traditionally stuck pens in the ground in front of the headstone in tribute; a few years ago, apparently, the cemetery added a “small pot” for the pens (I imagine it gets emptied once in a while, and also people steal them). According to one Reddit user, this tradition originated in a passage from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, in which Adams explains where ballpoint pens get to when you lose them:

Somewhere in the cosmos along with all the planets inhabited by humanoids, reptiloids, fishoids, walking treeoids, and superintelligent shades of the color blue, there was also a planet entirely given over to ballpoint life forms. And it was to this planet that unattended ballpoints would make their way, slipping away quietly through wormholes in space to a world where they knew they could enjoy a uniquely ballpointoid lifestyle, responding to highly ballpoint-oriented stimuli, and generally leading the ballpoint equivalent of the good life.

*

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Victor Hugo (1802-1885), Émile Zola (1840-1902), and Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870)

The same crypt in the Panthéon, Paris, France

What to know: So, it’s clear where the cool crypt is in the Panthéon, where many French luminaries are interred. Victor Hugo made it into the Panthéon right away, but he was the only one of the three to do so. Zola was originally buried in the Cimetière de Montmarte, but in 1908 his remains were moved to the Panthéon. During the ceremony, Alfred Dreyfus (yes, of the Dreyfus Affair—Zola was a supporter) was shot in the arm by journalist Louis Gregori in an assassination attempt. Dumas was originally buried in his hometown of Villers-Cotterêts, and was only moved to the Panthéon in 2002, for the bicentennial of his birth. But if it was a long wait, the style in which he was buried made up for it: his coffin was covered in blue velvet and inscribed with the words “Tous pour un, un pour tous” (All for one, one for all), and escorted to its new resting place by four Republican Guards dressed as Dumas’s musketeers. His elaborate re-interment ceremony was presided over by then-French president Jacques Chirac. Voltaire’s around the Panthéon somewhere, too.

*

Photo via Find a Grave

Photo via Find a Grave

Harper Lee (1926-2016)

Hillcrest Cemetery, Monroeville, Alabama, USA

What to know: Harper Lee was buried in her family plot, next to her parents and sister. The eulogy was delivered by her friend Wayne Flynt, and it was pre-approved by Lee herself—she had heard him deliver it as a speech (entitled “Atticus inside ourselves”) in 2006, and requested it for her funeral. “If I deviated one degree, I would hear this great booming voice from heaven, and it wouldn’t be God,” Flynt said. The funeral was private and quiet, but from the sounds of it, the whole town mourned.

Photo via Lorraine Hansberry Literary Trust

Photo via Lorraine Hansberry Literary Trust

Lorraine Hansberry (1930-1965)

Bethel Cemetery, Croton-on-Hudson, New York, USA

What to know: The inscription on her headstone is taken from The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window: “I care. I care about it all. It takes too much energy not to care. The why of why we are here is an intrigue for adolescents. The how is what must command the living which is why I have lately become an insurgent again.”

*

Photo via WNPR

Photo via WNPR

Mark Twain (1835-1910)

Woodlawn Cemetery, Elmira, New York, USA

What to know: Twain is buried with his wife in her family plot; each occupant has their own headstone, but the spot is now also marked with a twelve foot granite monument—”mark twain” being the riverboat term meaning twelve feet (or two fathoms), the depth at which it was safe for a steamboat to proceed. In 2015, someone stole the bronze plaque depicting Twain’s face from the monument, which was made in 1937 by artist Emfred Anderson. The thief was caught and sentenced to six months in jail.

*

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797-1851)

St Peter’s Churchyard, Bournemouth, Dorset, England

What to know: Upon her death, Mary Shelley left instructions for her son Percy and her daughter-in-law Jane to bury her with her parents—after all, she took Percy Bysshe Shelley to her mother’s grave to woo him—historians even think that’s where they first had sex, which is almost as goth as what she did with his heart later). But Jane thought the cemetery where her parents were buried was “a dreadful place” and so she and young Percy exhumed Mary Shelley’s parents and stuck their coffins in her carriage. According to biographer Miranda Seymour:

Jane was determined that the bodies should be reburied in St. Peter’s Church at Bournemouth; the vicar, having heard nothing to suggest that these were suitable candidates, was equally determined that they should not. He had not reckoned with Lady Shelley’s forceful nature. Bringing the coffins with her, she sat in her carriage outside the churchyard’s locked gate until the vicar, fearing the scandal in a tiny village, surrendered. A large common grave was dug on the high slope behind the church and, under cover of night, Mary’s parents were unceremoniously dropped into the pit.

As you can see from the inscription, Jane and Percy both eventually joined Mary Shelley and her parents in Bournemouth—and Percy, it is said, was buried with the remains of his father’s heart.

*

Photo via Mississippi Blues Travellers

Photo via Mississippi Blues Travellers

William Faulkner (1897-1962)

Oxford Memorial Cemetery, Oxford, Mississippi, USA

What to know: There are four plots in Faulkner’s grave—one for William Faulkner himself, one for his wife, Estelle, one for his stepson Malcom Franklin, and then a smaller one, which commemorates E.T., “an old family friend who came home to rest with us.” No one knows who E.T. is. Some have guessed that it’s his dog. Several other family members are buried in other parts of the graveyard. People love to leave alcohol, pennies, and cigars on Faulkner’s grave, and I heard a rumor that if you pour whiskey over Faulkner and Estelle’s graves, that by the time you leave his will be dry and hers will still be wet—because he loved to drink and she didn’t.

*

Photo via Pinterest

Photo via Pinterest

Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888)

Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord, Massachusetts, USA

What to know: She is buried near Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Nathaniel Hawthorne, in a part of the cemetery that has come to be known as “Authors’ Ridge.”

*

Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg at Kerouac’s grave; photo by Ken Regan, 1975

Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg at Kerouac’s grave; photo by Ken Regan, 1975

Jack Kerouac (1922-1969)

Edson Cemetery, Lowell, Massachusetts, USA, Lincoln Ave between Seventh Ave and Eighth Ave

What to know: Kerouac’s original flat stone grave marker includes his childhood nickname, Ti Jean, and marks the resting place of both he and his wife Stella Sampas, who outlived him by over 20 years. A new headstone was installed behind the old one in 2014, inscribed with Kerouac’s quote “The Road is Life.” There’s also video of the above visit that Dylan and Ginsberg made to the grave.

*

Photo by Christina Gunther

Photo by Christina Gunther

Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849)

Westminster Burial Ground, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

What to know: Edgar Allan Poe died under extremely bizarre circumstances in October of 1809 and was originally buried in an unmarked grave in the Westminster Hall and Burying Ground in Baltimore. After some time, when the spot had become overgrown with weeds, and was in danger of disappearing from memory altogether, the Sexton placed a grave marker there—but it was just the number 80. But when his aunt caught wind, a marble headstone was ordered. Unfortunately, it was destroyed in a freak accident (hit by a train) before it could be completed. In 1865, a memorial fund was taken up to create a new grave marker for Poe, and in 1874 they had finally raised the money. A monument was created by George A. Frederick—he got Poe’s birthday wrong the first time, but that was fixed. More vexing was the fact that there really wasn’t enough room around Poe’s grave to fit the new monument. Poe was exhumed and moved to the front corner of the ceremony, and a marker was placed on the original burial site (this is where the original Poe Toaster used to visit—it’s only pretenders who leave roses and cognac at the new site). Except, according to the Poe Society,

For uncertain reasons, this stone was initially misplaced completely outside of the Poe family lot. It was quickly moved to a more reasonable but still dubious location. Perhaps in part due to this confusion, but mostly because people simply love a good mystery, a strange rumor has persisted that the memorial committee failed to exhume Poe’s remains, instead moving those of some other poor soul.

The Poe Society finds this explanation dubious, but they have no other explanation.

*

Photo via Find a Grave

Photo via Find a Grave

Philip K. Dick (1928-1982)

Riverside Cemetery, Fort Morgan, Colorado, USA, Section K, block 1, lot 56

What to know: Although Philip K. Dick died in California, where he lived most of his life, he is buried next to his sister, a fraternal twin who died at six weeks old. Many sources cite this as one of the driving forces in his life and work; at the Independent, Kyle Arnold writes that Dick “literally and repeatedly tells readers that this is the key to understanding him.

Elements of the story of Jane’s death—Dick’s “origin story”—recur throughout his writing. The essence is that Jane died as a result of parental neglect, while Dick was miraculously rescued from the brink of death. Hence the motifs of the dead twin, the inhumane parental figure and miraculous yet equivocal rescue appear often in his life and work. As Dick said to his biographer Gregg Rickman, he “re-enacted” Jane’s story.

No intel on the significance of the cat.

*

Photo via Pinterest

Photo via Pinterest

Gertrude Stein (1874-1946)

Cimetière du Père Lachaise, Paris, France, Division 94

What to know: For a bonus, you can find Alice B. Toklas buried right next to her!

*

Photo via Travel Japan Blog

Photo via Travel Japan Blog

Natsume Sōseki (1867-1916)

Zōshigaya Cemetery, Tokyo, Japan

What to know: In his 1914 novel Kokoro, Sōseki describes a character’s burial in Zōshigaya Cemetery, and the monthly pilgrimages his friend makes to see him there.

*

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910)

Yasnaya Polyana, Russia, Tula region, Shekino district

What to know: Leo Tolstoy was born at Yasnaya Polyana and lived there all his life. Before he died, Tolstoy declared that he wanted to be buried “the place of the little green stick,” a clearing in the forest near the house. According to the official Yasnaya Polyana website (it’s now a museum):

Tolstoy heard the legend about the little green stick from his most beloved eldest brother Nikolai when a child. When Nikolai was 12 years old, he once told his family about a great secret. If it could be revealed, nobody would die any more, there would be no wars or illnesses, and all the people would become “ant brothers.” To make it happen, one just needed to find a little green stick, buried on the edge of the ravine in Old Zakaz, as the secret was written on it. Playing the game of “ant brothers,” the Tolstoy children settled under arm-chairs covered with shawls; sitting there and snuggling up together (like ants in their little home), they felt how good it was to be together “under the same roof,” because they loved each other. And they dreamed of the “ant brotherhood” for all the people. As an old man, Tolstoy wrote: “It was so very good, and I am grateful to God that I could play like that. We called it a game, though anything in the world is a game except that.”

All I know is, Tolstoy is buried in a full-on fairy grave. Nothing could be better.

*

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Where to find Ray Bradbury (1920-2012)

Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery, Los Angeles, CA

What to know: Ray Bradbury is buried next to his wife Maggie, who predeceased him by about a decade. His neighbors in Westwood Village Memorial Park include Marilyn Monroe, Donna Reed, Dean Martin, Natalie Wood, Burt Lancaster, Eva Gabor, and Wayne Rogers. Well, that’s LA for you.

*

Photo via Dustinations

Photo via Dustinations

Where to find Truman Capote (1924-1984)

Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery, Los Angeles, CA

What to know: Another one of Bradbury’s neighbors is Truman Capote, someone who is probably much more chuffed than he to be near Marilyn for eternity. But, um, is any of him actually there? Apparently, when Capote was cremated, his ashes were split between Joanna Carson (he died at her house, after all) and his partner Jack Dunphy. Carson kept her half of Capote in the room where he died, but they were famously stolen at a Halloween party—only to be mysteriously returned six days later. That’s when she bought the spot at Westwood Village Memorial Park. When Jack Dunphy died, his ashes as well as Capote’s were scattered at a place called Crooked Pond, near where the two shared property. In 2016, Joanne Carson’s estate auctioned off her portion of Capote’s ashes for $43,750. So it’s probable there’s actually not much left at Westwood, unless that’s where the new owner is keeping them.

*

Photo via Flickr

Photo via Flickr

Willa Cather (1873-1947)

Old Burying Ground, Jaffrey Center, New Hampshire, USA

What to know: Cather’s headstone includes a line from My Ántonia. It also maintains her “polite fiction” about her age, listing her birth as three years later than it actually was. Cather is buried next to her longtime partner, Edith Lewis.

*

Photo via Minstead

Photo via Minstead

Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930)

All Saints Churchyard, Minstead, Hampshire, England

What to know: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was originally buried in the rose garden of his estate; when his wife died, they were reburied together in Minstead, under an oak tree.

*

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Bram Stoker (1847-1912)

Golders Green Crematorium, London, United Kingdom

What to know: Hot tip: if you get cremated, there is absolutely no chance you will come back as a vampire.

*

Photo by José L Bernabé Tronchoni

Photo by José L Bernabé Tronchoni

Chester Himes (1909-1984)

Cementeri de Benissa, Alicante, Valenciana, Spain

What to know: At the time of his death, Himes had been living in the seaside village of Moraira, Spain for 15 years. It looks as though his wife was meant to join him there when she died 26 years later, in 2010, but I can’t discover whether or not she ever did.

*

Photo via Find a Grave

Photo via Find a Grave

Katherine Mansfield (1888-1923)

Cimetiere d’Avon, Avon, France

What to know: Last year, the Katherine Mansfield Birthplace Society requested to have Mansfield’s remains returned to Wellington, New Zealand, where she was born, but after a petition by Mansfield’s great niece to leave her where she was, the mayor of Avon rejected the proposal. A good thing, too, as many Mansfield scholars were against the idea, including biographer Gerri Kimber, who called it “”crass and ill-judged venture,” and said, “The body of Katherine Mansfield is not a Maori artefact taken overseas by a colonial ruler, which would justifiably need to be returned. She was a private individual who chose, alongside all her sisters, to spend her entire adult life away from New Zealand.”

*

Photo by Tom Duse

Photo by Tom Duse

Claude McKay (1889-1948)

Calvary Cemetery, Woodside, Queens County, New York, USA

What to know: The inscription on the gravestone comes from McKay’s poem “The Tired Worker.”

*

Photo via Pinterest

Photo via Pinterest

George Orwell (1903-1950)

All Saints’ Church, Sutton Courtenay, Oxfordshire, England

What to know: Orwell was buried as he was born, as Eric Arthur Blair, with no mention of his famous pen name. Though he was an atheist, he requested burial “according to the rites of the Church of England,” and though it was at first slightly difficult to find a good spot (the graveyards of London were apparently full when he died), he got it.

*

Photo via Find a Grave

Photo via Find a Grave

Elizabeth Gaskell (1810-1865)

Brook Street Unitarian Chapel, Knutsford, Cheshire, England

What to know: Elizabeth Gaskell is buried with her husband, William Gaskell, who was the minister of Cross Street Chapel in Manchester, England.

*

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Rebecca West (1892-1983)

Brookwood Cemetery, Brookwood, Surrey, England, Plot 81

What to know: Unlike Orwell’s, West’s headstone gives her pseudonym (which she borrowed from Ibsen’s heroine in Rosmersholm) top billing—above both her married and birth names.

*

Photo via Abroad in 2012

Photo via Abroad in 2012

Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881)

Tikhvin Cemetery, Saint Petersburg, Russia

What to know: Dostoevsky is buried near the poets Nikolay Karamzin and Vasily Zhukovsky. Inscribed on his tombstone is the following: “Verily, verily, I say unto you, Except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit.” (John 12:24)

*

Photo via Find a Grave

Photo via Find a Grave

Roald Dahl (1916-1990)

St Peter and St Paul Churchyard, Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire, England

What to know: Rumor has it that Dahl was buried along with some of his favorite things—snooker cues, chocolates, HB pencils, even a power saw. Whether that’s true or not, there’s usually some of his favorite things on top—despite the fact that he was a complete jerk, gentle children still come by and leave toys by his grave. More fitting, perhaps, is the fact that when biographer Jeremy Treglown visited the grave, he found, instead of the flowers left on other plots, “[Dahl’s] favorite vegetable: a large, handsome, tough-skinned, many-layered onion.”

*

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Robert Frost (1874-1963)

Old Bennington Cemetery, Bennington, VT, USA

What to know: Robert Frost’s gravestone is flush with family members. But in case you can’t read the inscription under his name, it is “I had a lover’s quarrel with the world.” Frost’s poem “The Lesson for Today” ends with these lines:

I hold your doctrine of Memento Mori

And were an epitaph to be my story

I’d have a short one ready for my own.

I would have written of me on my stone:

I had a lover’s quarrel with the world.

Someone, apparently, took him at his word.

*

Photo via Find a Grave

Photo via Find a Grave

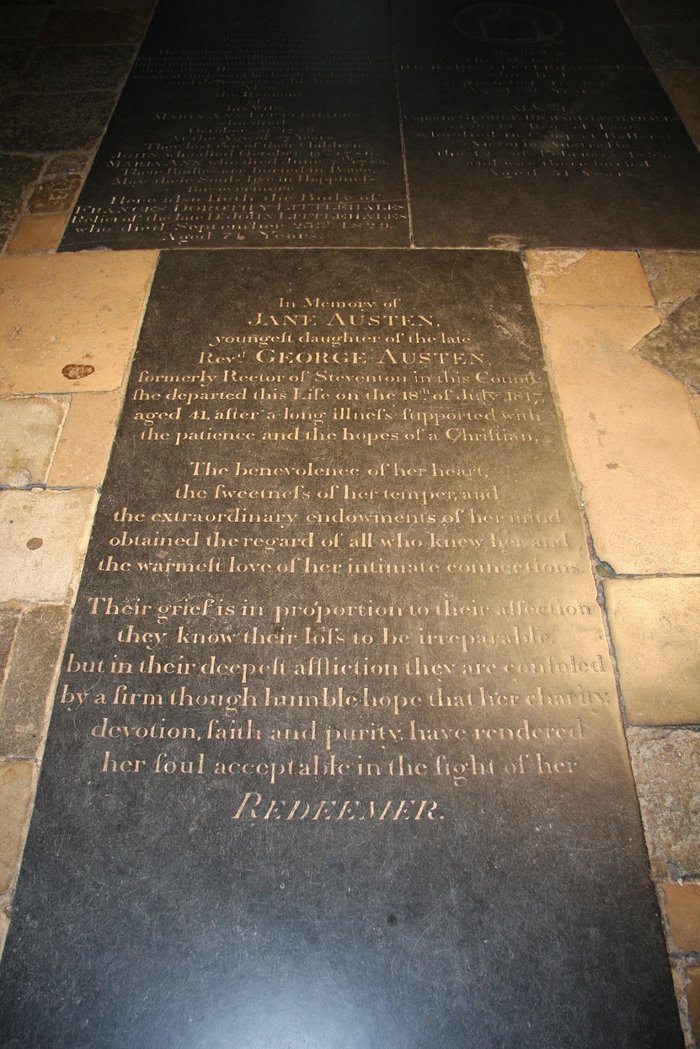

Jane Austen (1775-1817)

Winchester Cathedral, Winchester, England

What to know: When Austen was first buried in the Cathedral, her memorial stone did not mention her books, but rather went on and on about what a nice young lady she was. In 1872, a brass plaque was added to fix that. She now has three memorials in the Cathedral: her original stone, her plaque, and a memorial window.

*

Photo via Find a Grave

Photo via Find a Grave

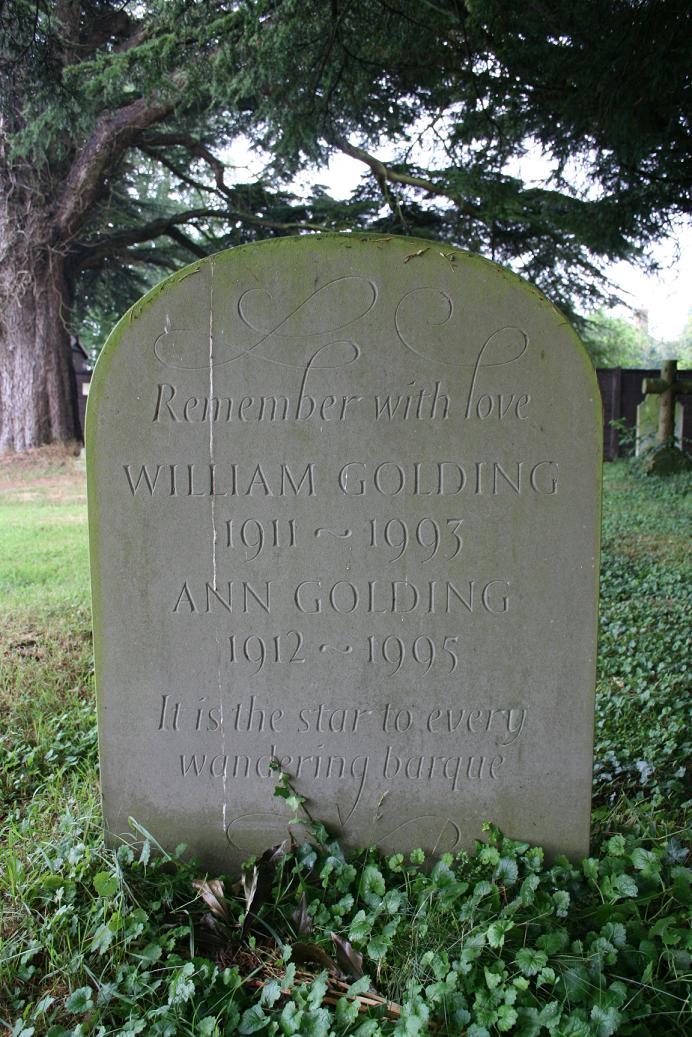

William Golding (1911-1993)

Holy Trinity Churchyard, Bowerchalke, Wiltshire, England

What to know: The inscription, “It is the star to every wandering barque” is from William Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116.

*

Photo via The History Blog

Photo via The History Blog

Miguel de Cervantes (1547-1616)

Convento de los Trinitarios, Madrid, Spain

What to know: At his request, after his death in 1616 Cervantes was buried in this convent, but when the convent was rebuilt years later, his remains were lost. Only in 2015 were they rediscovered and reburied in the Church of the Trinity. (The above plaque is on the outside of the Convento de los Trinitarios.)

*

Photo via Flickr

Photo via Flickr

Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926)

Cimetière de Raron, Raron, Switzerland

What to know: Before his death, Rainer Maria Rilke wrote his own epitaph, which translates to:

rose, o pure contradiction, desire

to be no one’s sleep beneath so many lids.

His grave is surrounded by rosebushes, appropriate, because as William H. Gass put it:

The myth concerning the onset of his illness was, even among his myths, the most remarkable. To honor a visitor, the Egyptian beauty Nimet Eloui, Rilke gathered some roses from his garden. While doing so, he pricked his hand on a thorn. This small wound failed to heal, grew rapidly worse, soon his entire arm was swollen, and his other arm became affected as well.

A more romantic cause of death one could not wish for (though I suppose it did not feel that way to him).