One danger is that the reviewer’s novel may stand in the way of the author’s. Sometimes the two are incompatible: when the Canadian writer Marian Engel describes the adulterous hero of Injury Time as having been “instructed to clean up his act,” another, mid-Atlantic Beryl Bainbridge is brought to mind. A further danger is that mimicry may become parody (one of the standard ways of dismissing a bad novel is of course to ape its mannerisms), and a reviewer adopting the manner of the novelist may do the novel an injustice where no injustice was intended.

When a reviewer mimics a novel simply as a way of describing it (without, that is, any pejorative intentions) he is in some sense taking it over, as if he too could predict how the characters might behave. Those contemporary novels that disclaim verisimilitude make it difficult for the reader to enter their world; indeed, by making an issue of their own fictiveness they deliberately set up barriers against it. In their more extreme Sarrautian forms they may invite him to participate in the invention, but that in itself is a way of pointing up what would in these cases be seen as the fallacy that fiction imitates life.

More realistic novels by contrast offer the reader a whole new world with new friends (or enemies) and new places to go to. “We follow the life of her heroine,” a grateful reviewer reports, “through a circuitous route where we meet a plethora of well-drawn characters and visit a number of interesting places.” But reviewers in discussing this world are inclined to be over-eager:

Perfectly observed details—a steaming mug of tea in a transport café, a misfired blind date in a lurid pub—make you feel you’re living Desmond’s life.

It may be that the best fiction has a reality that reality itself hasn’t got (however well we know the details of other people’s lives we don’t often feel we’re living them), but the examples here don’t support the claim that is made for them, and the reviewer, mistaking familiarity for something better, has been hasty in casting aside her own life in favor of Desmond’s. It’s the same with characters’ emotions which too readily become the emotions of the reviewer: “I relaxed as much as the hero and his wife do when she burns her ovulation charts.” It’s hard to believe in that degree of empathy.

A critic who professes to share all the characters’ ups and downs tells us too much about his own responses. David Lodge reviewed Mary Gordon’s Final Payments. He thought it a good novel and one of its qualities, he said, was that it engaged the reader’s sympathies on the heroine’s behalf: “It says much for the power of Ms Gordon’s writing that the reader feels a genuine sense of dismay at the spectacle of the heroine’s mental and physical breakdown.” The point he is making is very like the one being made by the reviewer who said she relaxed when the hero’s wife burned her ovulation charts, but he is putting the emphasis on Gordon’s writing rather than his own sensibilities.

Generally speaking, the more highbrow the publication the more self-effacing—or apparently self-effacing—the reviewer. A critic in a popular paper may, rightly, claim that but for him a whole section of the literate public might never hear of certain writers and that this enjoins on him the necessity to be forthright and uncomplicated.

Experiment, symbols, allegory: reviewers don’t often like them.Auberon Waugh, who reviews novels in the Evening Standard, is such a writer. One of his habits is to complain of personal suffering—excruciating boredom, a pain in the ass—on reading novels he doesn’t like; another to award prizes—“my gold medal . . . a peerage or some luncheon vouchers to go with it”—to those he does. Waugh sees himself as deploying the common sense of the common man: a reviewer in a more serious journal or newspaper has to suggest expertise, give evidence of special qualifications (though even here there are some who choose to make their comments personal as an excuse for slipping out of responsibility—to say “I enjoyed it” is sometimes a way of saying “little me I enjoyed it”).

Whatever the publication, it is probably fair to say that most readers of reviews do not go on to read the novels themselves: in that sense reviews act as substitutes for the novels, incorporating as a further dimension the experience of the reviewer in reading them. Hence perhaps the documentary interest reviewers show in the lives that are led in novels (the more sociologically particular the world that is described, the more confident the praise: “exactly conveys the tone and feel of a theater”; “quite faultless in its delineation of every aspect of the cinema”).

Experiment, symbols, allegory: reviewers don’t often like them (“there may be an allegorical meaning here that I’ve missed; if there is, Mr Keating isn’t pushing it, and I’m all for that”), and novels that have a grand plan or an easily detected message are rarely well received. Time and again a book is praised for understating its intentions:

Getting Through leaves so much unsaid that what is left—the story itself, pared down—becomes the reflection of great things.

The purpose of their encounter is never formulated by authorial commentary or by the intrusive use of imagery.

The book never loses its distant innocence of expression—as if the full surface of the world can only be conveyed by a prose that neither moralizes nor obtrudes.

Authorial unobtrusiveness (“clear spare sentences,” “direct factual observation,” “clear but unemphatic patterns”); modesty of effect and affect—these are the qualities reviewers speak well of. What is wanted is not “hectic” plotting but “a meticulous circumstantiality,” “not clashing symbols but uninsisted juxtapositions.”

On the other hand, it is the reviewer’s business to make explicit what the author has been commended for rendering inexplicit; to spell out (“in their interaction they retrace the patterns of social intercourse familiar to us all”) and to extrapolate (“Violence, Bainbridge seems to be saying, is as casual, as impersonal as the shadows we know”). Novelists may not be allowed to moralize but reviewers do it all the time:

To him, the conquest of pride is ultimately more important than the conquest of Prague. It takes a lot of courage to suggest this, but the only real antidote to the think-alike, talk-alike herd instinct of Marxism is the liberation of your own soul from second-hand thinking and borrowed feelings.

I don’t accept any form of racism and I applaud Mr Brink’s honest novel.

And if writers don’t moralize, or are told that they ought not to, they are nonetheless praised in moral currency: “Where [the characters]—and Miss Sagan—truly shine is in the sections that describe their acknowledgment of a colleague’s cancer.”

Praising is the reviewer’s most difficult task. Allocated, in most newspapers, a thousand words in which to give his views of three or four novels of average merit, he hasn’t the space to build up the case for each one and must therefore resort to an encomiastic shorthand. In what is usually the first part of a review, where we are told what sort of novel it is and what happens to whom, the novel itself does much of the work; and if a reviewer gives a coherent account of it and makes the characters seem interesting, he has already done a great deal to commend the book to the reader’s attention.

A skilful reviewer will also interweave judgment and description. “Bernice Rubens’s new novel is convincing about the need for people to see plots in their lives”: that “convincing” carries conviction because of what follows it; if it had been placed at the end of the review—in the phrase “a convincing novel,” for instance—one would scarcely have heard it.

Since the vocabulary of praise is limited, the same words occur again and again, while some acquire emblematic loadings. Truth, for example. When a reviewer says a novel has “an overall ring of truth,” he may just be talking about “plausibility” and making it sound like something more important. But it is the final adjectival blast that offends. Marvelous, delightful, brilliant: it is hard for a reviewer eager to say good things about a novel to avoid such words, yet they have been used so often in connection with novels which, when compared, say, with Our Mutual Friend, are merely mediocre that readers may find some difficulty in giving them credence.

It’s true they are important to publishers, who use them in their advertisements, and a reviewer anxious to promote a novel will be sure to include a few for the publisher to quote, just as many literary editors, alert to the danger of one novel review sounding very like any other novel review, will want to cut them out.

Some reviewers, it’s obvious, are better writers than others, but even among good writers there are recurrent mannerisms.Reviewers are varyingly responsive to these embarrassments, but the stratagems they may resort to for avoiding the clichés used by their less self-conscious colleagues quickly become clichés themselves. One doesn’t often come across the simple phrase “a marvelous novel” nowadays: the fashion is for triads of adjectives (“exact, piquant and comical,” “rich, mysterious and energetic”) or for adjectives coupled with adverbs—“hauntingly pervasive,” “lethally pithy,” “deftly economic”—in relationships whose significance would not be materially altered if the two partners swapped roles—pervasively haunting, pithily lethal etc.

The praise is made to sound less bland by the use of negatives (“a completely unponderous story”) or of oppositions indicating that a novel hasn’t made too much of its virtues (“stylish but troubling,” “unforced yet painful”); and by various minor syntactic devices: one novel “is saved by energy from pretension,” another is rescued from overfamiliarity “by the author’s evocation of certain oblique and mysterious states of consciousness”; one “gives us a feel for our own loony culture that is so recognizable we blink with shame and embarrassment,” another produces “shocks so true to life that they hardly seem paradoxical.”

Some reviewers, it’s obvious, are better writers than others, but even among good writers there are recurrent mannerisms. Wordplay is one: “Amid stern actualities, Kundera gamely concocts (like Sterne, and hence unsternly) stories about people playing games.” Verbs are preferred to adjectives: a “story spurts and fizzes,” a “sense of humor crackles”; and so sometimes are nouns, usually in their plural form—intricacies, acutenesses and so on.

The abstract and the concrete may be unexpectedly juxtaposed: “details slither rat-like into their lairs”; and rather than speak directly of a novelist’s talents, reviewers have lately been much inclined to anthropomorphize the novel: “grinding on like that is, Hanley’s fiction knows, the hardest of all feats.” The desire to avoid clichés is strong and commendable, but leads to some perplexing formulations: “Through all such knots and breaks of time, a rare aptitude for patience is the unassuming form of Trevor’s irreplaceable imagination.”

Novel reviews don’t of course end like novels: novelists seldom finish off their work by praising or scolding their characters, though they may (or may not) award them happy lives. But what is wanted of a reviewer is much the same as what is wanted by the reviewer: a modest, unemphatic originality, a meticulously circumstantial account of the novel’s merits, and a plausible (or should I say truthful?) response to them.

—1980

___________________________________________

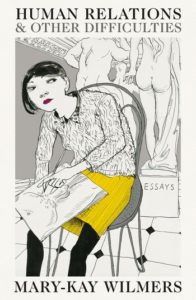

Excerpted from Human Relations and Other Difficulties: Essays by Mary-Kay Wilmers. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, August 27th 2019.