How to Read a Play as a Manual for Novel Writing

Julia May Jonas on Tempo, Audience, and More

Several years ago, I ran into a neighbor—a fiction writer and essayist—in a coffee shop, where he was reading Harold Pinter’s The Dumbwaiter. “I like to read plays before I write fiction because they remind me how to start writing,” he said.

At the time, I didn’t understand what he meant—I thought the prose I wrote and the plays I wrote were diametrically opposed. I teach playwriting to undergrads, and I tell my students early and often that a play has more in common with a song or a poem than with a novel. In playwriting groups it’s often a veiled insult to be told that your plays are “novelistic”—that’s when you know your play is overwritten and not theatrical. I always thought if I wanted to write a novel—which I did—I had to push what I knew about playwriting away: that other than both being made up of words the two forms were at best distant, and at worst, incompatible.

In March 2020, when I had a big theatrical project postponed indefinitely, I began working on the novel that would become my debut. From the start, I could tell there was something different about my writing, something that excited me—it had an energy, a voice. Once I finished the first chapter, I knew I could keep going. And as I continued to write Vladimir, the story of an English professor’s captivation with a younger colleague, I realized that I was pulling directly from what I knew about playwriting. Here are three aspects I considered:

Change: I heard this secondhand from someone who worked with the playwright Christopher Durang: he was giving them notes and apparently said something like, “Listen, if your play takes off in New York, it should land in Los Angeles. Or at least Milwaukee. But not back in New York.”

With novels you don’t have to think in scenes, but it can certainly help.

This reminded me of my children. Since they were babies, both my children love any activity that allows them to permanently alter the state of an object. Ripping, tearing, cutting, baking—there is something intrinsically satisfying about changing the material world.

In playwriting you can’t include a scene in which nothing changes or shifts, as it would feel (to you and the audience) totally pointless. And because theater is essentially constructed from scenes, there is a built-in imperative for motion—something happens, then something else happens because of that, then something else happens because of that, and in each instance we’re seeing the state of the world or story being continually reshaped.

Similarly, in a novel, I try to ask myself: How does each moment indelibly adjust the world of the book? With novels you don’t have to think in scenes, but it can certainly help. Every scene in Pride and Prejudice introduces a new complication to the Bennet family. And this doesn’t have to happen only with plot. This sense of progression, or change, can be achieved through an accretion of knowledge, or an aggregation of language—like how each line in David Markson’s Vanishing Point builds upon the last line, creating, word by word, a more complex and immutable whole.

When writing Vladimir I was always conscious that something about the world needed to be different at the end of each chapter, something new and irrevocable, whether it was an adjustment in the world around the narrator, something she did, or something she realized—so that when we entered the next chapter we commenced on altered ground.

Tempo: We know that rhythm is essential in writing; as Virginia Woolf said, “Style is a very simple matter, it is all rhythm.” The rhythm of speech is often what makes a play delightful, tragic, beautiful. I’ve never read a strong play that doesn’t have a strong musical sense to the dialogue.

However, because plays are durational, there are two ways in which rhythm must work: both moment to moment and in the overall experience. A play typically needs to take an audience through at least 75 minutes in their seats, so it needs both a sense of established tempo and changes to that tempo, much like you might have in a musical composition.

An excellent recent example of this is in Sarah DeLappe’s The Wolves, a play about high-school-aged female soccer players. Throughout most of the play the scenes are overlapping, funny, staccato—meant to be played quickly, like an allegro movement of a symphony. After a tragic event, though, the penultimate scene is a long, legato monologue by a character we have never met before. As audience members, the shift in tempo works on our bodies as well as our minds.

An attention to tempo enlivens fiction as well. Joyce demonstrates this in Portrait of An Artist as a Young Man with that famous priest’s sermon. The book radically switches speeds and we are trapped listening to the entire fire and brimstone address, written so that we experience, rather than simply understand, the imprint it makes on Stephen Dedalus.

In books like The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson luxuriously explains scholarly anecdotes, and then follows them with short, often personal sentences, so that we feel the desire of the mind to explain, and then the blunt force of emotion that sweeps intellectualization away.

I’m always thinking not only about the character’s voice, but who the character might be addressing.

There is a moment in Vladimir in which the narrator offers the title character a detailed and favorable response to his book. For a deliberately taut novel, her reflection stops the story for a while, and I had considered cutting her speech down, summarizing it from a distance. Then I realized we needed to squirm a bit—we needed the space to inhabit the scene and her delivery of these overly-flattering, rather pretentious thoughts to this man. This is a way she knows how to seduce (or thinks she does), and we need to endure it, embarrassed and exhilarated, in real time.

Audience: One essential factor in writing a theatrical monologue for a character is thinking about who exactly the character is talking to. Is it a priest? Or a judge? Their best friend or their worst enemy? Their lover or their mother?

That choice will affect how the character chooses their words, what they admit and what they omit—and keeping that audience clear in one’s mind will focus the work.

I find I apply this lens when I’m reading fiction, too. I’m always thinking not only about the character’s voice, but who the character might be addressing. Some fiction writers make a choice to be explicit about the listener; Rachel Cusk, in Second Place, writes the entire book as a letter to a person named Jeffers. (You can tell the narrator wants to charm Jeffers, and to present herself thoughtfully and with erudition.) Kazuo Ishiguro, in Remains of the Day, has his narrator carefully and judiciously doling out his story with only the slightest hints of truth, as though he doesn’t trust his audience. And this doesn’t have to only exist in first-person fiction. Denis Johnson, in many of his short stories, recounts the narrative as though he’s a loquacious stranger, 3 drinks in, sitting next to you on a bar stool.

As I was writing, I thought of Vladimir as a very long monologue—and I imagined the narrator sitting with a friend who is her best possible audience, someone she loves to shock, surprise, make laugh, confide in. A friend that she knows she can entertain. Someone she never speaks down to. A person she feels comfortable revealing her entire self to but also someone she wants to impress. There might be glasses of wine in hand, scraps of food left on the table, dishes piled up and ignored until the morning, after the story has been told.

__________________________________

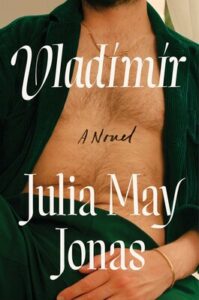

Vladimir: A Novel by Julia May Jonas is available via Avid Reader Press.

Julia May Jonas

Julia May Jonas is a writer of fiction and plays and founder of the theater company Nellie Tinder. She has taught at Skidmore College and NYU and lives in Brooklyn with her family. Vladimir is her debut novel.