How to Make Friends With an Animal On Facebook

Alexander Pschera on the Digital Closeness Between Humans and Animals

A Little Story of Empathy

Shorty the waldrapp is a Facebook friend of mine. He’s a strange bird. A little unconventional, but not unlikable. He looks much older in his profile picture than he actually is. He’s bald, his skin wrinkly and furrowed. However, he gives off a tough, tenacious, and thoroughly youthful vibe. He wears his thin neck feathers in a crazy plume. He spends winter in the south, in Tuscany, for health reasons.

Shorty doesn’t yet live independently in the wild; rather, he’s part of a reintroduction program. He was raised by humans and is now learning what life in the wild is all about, because Shorty has forgotten what it means to fly over the Alps in search of warmer climes, come autumn. His human foster parents have the arduous task of teaching him how to migrate. They accompany his first migration in an ultralight aircraft, in the hopes that this action will activate a genetic memory in the ancient bird species that will allow him to guide others of his kind over the mountains next autumn. In order not to lose him, he has been tagged with a GPS tracker that sends signals online via satellite. This allows people to see where Shorty is at all times. The rest of the waldrapp flock are also equipped with tracking units. The data are made public on a Facebook page. Almost every day, visitors can view maps for a detailed account of the waldrapps’ current location, how they are doing, and what they may recently have encountered. The interaction between humans and animals on the Facebook page is intense. Waldrapp friends search for the animals, photograph them, and upload the images. However incomplete, a multifaceted picture of these animals’ everyday lives thus emerges.

There are many other ways in which social media could be used for communication between humans and animals. Taylor Chapple is responsible for tagging great white sharks in the North Pacific. He works at the Hopkins Marine Station of Stanford University. Shark Net, the attractive iPhone application he and his team have developed, allows users to follow individual great whites. The animals do not yet have a Facebook page or blog, though. “It’s coming,” Taylor stresses. “It’s in the pipeline.” The goal for the great white, an endangered species, is also to dismantle preconceptions and familiarize people with the sharks’ way of life. Social media can help bring the sharks closer to humans. Until the site has been launched, however, the European Waldrapp Project remains the benchmark for demonstrating how digital communication with animals can work, as well as its natural limitations.

Shorty is my first animal Facebook friend. When he started on his way from the breeding colony in Burghausen, east of Munich, to his Italian wintering grounds last fall, I was eager to see how it would feel: to be in direct contact with a wild animal, to soar over the Alps with this bird, peering over his shoulder like the Swedish fairy tale character Nils Holgersson on the backs of the wild geese. The very notion of “following” a wild animal, in the truest sense of the word, staying hot on its track, promised totally new experiences and insights that far surpassed anything out of a documentary. It was the real-time allure that drew me in.

The second time I visited the page to check on Shorty’s current status, however, some doubts crossed my mind: Wild animals as Facebook friends? What has the world come to? An increased closeness to nature is desirable, but does this return to nature have to be digital? Isn’t it better to go into the woods and forage for mushrooms? Isn’t the Net more a part of the problem than a part of the solution?

As soon as Shorty struck out for his wintering grounds, however, the doubts lifted and things got interesting. It didn’t take long for the emotional tie to the animal to form. I was sharing in the thrill of things. How many miles will Shorty manage today? Will he reach his destination? Will he find the right way? That sounds easier than it is. Shorty actually did lose his way. He landed in Switzerland, in an area that is too cold and desolate, even in late autumn, for a waldrapp to spend its winter. Along with many others in Shorty’s network of friends, I immediately wanted to know: Does the bird stand any realistic chance of survival down there in the ice, snow, and cold? Even those in charge of the waldrapp project doubted the site’s suitability as a winter spot. Johannes Fritz, the project director, wrote the following concerned Facebook post on January 18:

No word from Shorty for several days now; have any of our Swiss friends seen him recently? It would appear as though the weather has changed in Switzerland, now, too.

Three days later, and still no sign of him: There have been no more reported sightings of Shorty since last Wednesday.

It would appear as though he’s flown on, perhaps even just closer to Lake Zug. Based on past experience, I’m optimistic that Shorty will manage in the current weather conditions, especially because he clearly found enough food before the weather changed. In consultation with our team, staff members at the Goldau Landscape and Animal Park have been trying for some time to attract the bird with food, unfortunately without success. Still, many thanks to all involved! We will now wait till new sightings are reported, and in the meantime, we’re thinking about how we might catch the bird, should he fail to respond to our attempts at luring him in.

Catching the waldrapp proved a difficult undertaking. On February 11, Johannes Fritz therefore posted a call to action intended for Shorty’s Facebook friends in Switzerland:

In order to launch a new attempt at catching Shorty, the bird’s location needs to be at least halfway predictable. We are therefore calling all people on Lake Zug who have the time and motivation to search for and observe the bird. It would be ideal to know where he sleeps, or perhaps a certain meadow where he spends his days. … We will immediately post new sightings here on Facebook, in order to assist in the search for Shorty.

The appeal worked. Local Shorty fans supported the search for the waldrapp and uploaded their photos onto the Facebook page. The rundown on February 12 was as follows:

Herr Brunhold has some really interesting information on Shorty’s whereabouts:

Saturday, 02/09/13, 16:00: Brief spells of sunshine and snowfall. Town of Risch, Zweiern area (south, near Freudenberg Palace). Shorty amongst the graylag geese.

Sunday, 02/10/13: Frequent sun, but cold. A passerby reports a Shorty sighting in Risch, near Dersbach Manor, north, near Freudenberg Palace.

Monday, 02/11/13, 15:15: Heavy cloud cover, occasional bursts of sunshine, around 0ºC. Risch, Dersbach Manor, north, near Freudenberg Palace, in a sheep pen. Shorty pecking busily at food in the sheep pasture. Approx. 20 m distance from the sheep.

The waldrapp appears to have made his home on the western shore of Lake Zug, somewhere between the public beach in Hünenberg and the village of Buonas. This is, however, an area spanning about 2.5 km.

Herr Brunold’s other photos show the bird eating. His condition still appears to be good.

It seemed impossible to catch Shorty without professional help. February 14:

Our associates at the Max Planck Institute in Radolfzell have agreed to help catch Shorty using socalled cannon-nets. I think this will improve our chances of finally catching the bird, in order to unite him with others of his species in Tuscany. Because as well as Shorty is clearly managing in Switzerland, it is far from adequate for him. And when we remember the fact that he belongs to a group of about 25 migratory waldrapps, then our efforts are certainly justified in trying to ensure his optimal chances of survival.

Despite all attempts, the animal still evaded capture. There was no shortage of helpful suggestions from the increasingly active waldrapp community:

Maybe they should try using “live bait” … put his best pal in a live animal trap … A dummy … + play a recording of their “song” … they use CDs to attract swifts and that works.

Criticism of the attempts at capture soon entered the discussion. Several animal lovers argued that the waldrapp should be left to its own devices. It’s a wild animal, after all, that may need human support up to a certain point, but that must then learn to live on its own.

Shorty’s odyssey, meanwhile, seemed to know no end. On April 3, Johannes Fritz posted a passing update:

Just a little new info on Shorty, reported from Switzerland. He was seen with the graylag geese yesterday, Tuesday, by Herr Simeonidis on Lake Zug, apparently still in good shape.

There will not be any new attempts at capture, as long as conditions do not unexpectedly change. We expect to see our Swiss bird back at his breeding grounds in Burghausen in the coming spring, and we are already looking forward to it.

In the meantime, I hope to continue receiving reports of sightings from our dedicated Swiss friends.

As the first gray-brown chicks start hatching in Burghausen in May, it became evident that Shorty had decided to stay in Switzerland for the time being. On May 8, we read:

There’s been news from Shorty. Martin Brunhold visited him a few days ago and had this to report:

“After strong hailstorms in Risch on the evenings of May 1 and 2, I was gone for a few days and couldn’t keep an eye out for Shorty until yesterday. I found him at 15:00 in a field near Buonas, in sunny weather. About an hour later, he was poking around a mown meadow near Zweiern, alone, and he was not bothered by the people out for their Sunday stroll. I could tell that many of these walk ers knew our waldrapp, based on their conversations and reactions.”

Eventually, Shorty did return home to his flock. While they soared, shining black, over the mountains, I sat at home in front of my computer, watching the blue and red dots moving across the map, and breathed in the air of freedom.

The wilderness is undergoing a revival in the living room.

The Similarity of the Other

But how close is this digital closeness really? And what does it say about the possibilities of a renewed interaction between humans and animals? The existential bond between living beings is what first made animals attractive to humans as companions. This half playful, half serious closeness has gotten away from us—entirely without the influence of the Internet. The linchpin of the new ecology, the springboard for revaluating the paradigm of green ideology, is the awareness humans have of animals. Classic green thought is built upon the idea that all animals behave in a way that is typical of their species. It treats animals like an abstract group, and views single members of this group not as individuals, but as interchangeable representatives of their species. An emotional tie cannot be formed with an abstract image of a species. A symbolic representative will never be an individual. The Animal Internet’s opportunities for social interaction allow for breaking through the logic of abstraction. They allow humans to connect socially with wild animals, as we experienced concretely with Shorty.

Only this can help create a new view of nature. “We should not,” says zoologist Reichholf in this regard, “write off this kind of interactive connection as ‘pathetic fallacy.’ Many animals would benefit from emotional humanization … [because] it’s the closeness to other living beings that we’re missing and that conservation policies are blocking in such a ridiculous manner.”

The digital cosmology emerging in tandem with the Animal Internet relates to this weakened, but not totally extinguishable, human empathy for animals. In the past, animals were not merely practical helpers and useful partners in everyday human life. Animals are closely connected to the emergence of human cultures and civilizations. The first images humans painted on cave walls were of animals. The first paints humans used were probably animal blood. According to one theory, human language began as an imitation of animal sounds. This argument is made both by Plato, in Cratylus, and Rousseau, in his Essay on the Origin of Languages. Ancient mythology and poetry provide a living mirror of this symbiosis. They depict humans, gods, and animals in the flowing transitions of metamorphosis and metempsychosis, of morphogenesis, shape-shifting, and rebirth. Ovid’s Metamorphosis contains many examples of this: Jupiter changes Lycaon into a wolf and Io into a cow, Diana transforms Actaeon into a stag, Athena recasts Arachne in the form of a spider, and so on.

Experiences with the animal kingdom allowed humans to take possession of the world, both practically and metaphysically, to understand physical connections, and to guess what was happening beyond the realm of the visible. Animals provided the structure for human awareness of the world around them. They gave it form and shape, they made the unknown their own. Animals were used as signs and symbols for defining the cosmos, making the infinite and incomprehensible vastness of the universe seem less alien, and bringing it all closer to humans. The wealth of animal forms predestined them for use in making the blanket of stars describable, in the first place. When humans looked at the heavens, they saw in them the creatures that surrounded them on Earth: eight of the twelve zodiac signs are animal-based. In Hindu cosmology, the earth is carried by elephants standing on the backs of turtles. People also used animals to reduce the threat of the unknowable by interpreting their behavior to prognosticate, again calling to mind the proverbial canary in a coal mine. Humans were as wont to read the entrails of sacrificed animals as they were to watch birds in flight for signs about the future.

It’s easy for modern humans to write off this kind of divination as superstition or magic, and to consider themselves above the foolishness of ancient peoples. This supposed foolishness, however, exhibits an essential human trait, namely the tendency to describe the unknown— which is fundamentally threatening and potentially destructive, given our inability to plan for it—in terms of the known, thereby making it more tangible. Even today, humans are constantly pushing the boundaries of their emotional “safe spaces”—better known in today’s jargon as “comfort zones”—and in doing so, they use all manner of traditional symbols, including animals. In a thousand years, humans may find our planting a flag on the moon to be as grotesque and irrational as we consider hepatoscopy, the liver examinations practiced by the Babylonians and Etruscans, to be an absurd method of prognostication and diagnosis. Upon seizing the moon, however, the act of erecting the flag was an important symbol, not only of victory over the Soviet competition, but of triumph over what the moon represents—the cold and the unknown. There’s nothing different between this flag declaration and humans charting the night skies with the animals they hunted and that were part of everyday life.

For prehistoric humans, therefore, animals were not only of this world, but most decidedly of the great beyond, as well. Animals participated in both worlds. They were at once mortal and immortal. And humans treated them as such: they prayed to them and hunted them. They idolized them and killed them. Animal sacrifice, a rite common to many religions, was an expression of this otherworldly aspect of existential dualism. During sacrifice, the animal is not simply killed or slaughtered; instead, it’s handed over in a symbolic act to the god being honored. It’s freed of its utilitarian functions and released to a higher order. Viewed from afar, even bullfighting is reminiscent of this type of sacrifice. The human who kills the sacrificial animal always surrenders a part of himself, if not physically then symbolically. In following the rules of a ritualized slaughter, he is submitting to a higher order. A part of himself is always offered to the gods, as well.

Even humans today—who live in an overly technological world, in which real animals are encountered either as domesticated pets or caged specimens at the zoo—can comprehend the reason behind this. Animals resemble humans in many profound ways. The similarities start with anatomy and end with social behaviors. Animals have blood that pours from their wounds. Highly developed species have bodies made of bone, muscle, and skin, like those of humans. Most important, animals have eyes with which they look at humans, and behind which humans can sense an active awareness. In certain circumstances, even the gaze of a carp can be thought-provoking. An animal’s gaze can convey both joy and pain. Furthermore, animals can learn. They react to our actions, they adapt to our behavior, they possess social intelligence, and they create differentiated social groupings that are sometimes superior to those of humans.

Still, animals are not humans. They are similar to humans, but also differ from us. This similarity, in the absence of identity, as one might say, is at the heart of the human-animal relationship. Animals are mute. Or rather: they do not speak a language we can understand. We don’t know if and how they think, or if they have a conscience that parallels the human conscience. Direct dialogue with them is impossible, even if horse whisperers or dog trainers would have us believe otherwise. In addition, as social beings, humans typically prove superior to animals. When they get organized—for instance as a hunting party—humans can overpower even the wildest and most dangerous of animals using relatively simple means. Prehistoric humans were able to slay mammoths employing the most primitive methods—and these were animals with the obvious advantage over humans in power, size, and speed. This organizational superiority has allowed humans to rule the world, not animals.

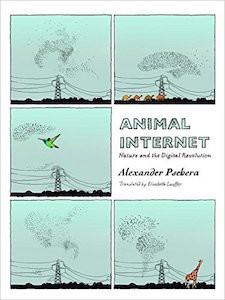

From ANIMAL INTERNET. Used with permission of New Vessel Press. Translated by Elisabeth Lauffer. Copyright © 2016 by Alexander Pschera.

Alexander Pschera

Alexander Pschera, born in 1964, has published several books on the Internet and media. He studied German, music and philosophy at Heidelberg University. He lives near Munich where he writes for the German magazine Cicero as well as for German radio.