How to Feel Like a

Human Online

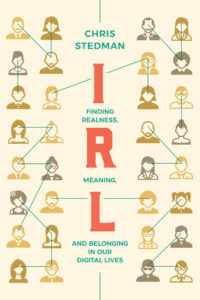

Chris Stedman's Deep Dive Into Our Internet Selves

In one of my favorite books of 2019, Rising, Elizabeth Rush writes of finding a phrase in an essay on Alzheimer’s: “sometimes the key arrives before the lock.”

I was helping my mom take care of my stepdad, who has Alzheimer’s, at the time, which I assume is why the line jumped out at me. I took a photo of the page it was on, added the photo to the “favorites” album on my phone and tucked it away in case I needed it in the future. But I had no idea then how apt that phrase would come to feel just a year later.

For the last four years, I’ve been fixated on the question of what it means to be “real” in the age of deepfakes, catfish, and digital performance. My search for a better understanding of online realness began when, at the tail end of my twenties, everything that I thought made me who I was changed all at once: my long-term relationship ended, then my job, then my near-decade living on the other side of the country from the rest of my family. So many of these were things I’d post about online, swept up in the sea of digital boasts and brags to which we’ve all grown accustomed. Yet even as the things I thought gave me value fell away, I reflexively continued to post online as if all was well. In a world where we constantly absorb the message that the internet is fake, or at least less real than offline life—and are at the same time called to engage ever-more important pieces of who we are in digital space—I felt split between a fractured self and my digital composite.

So I went looking for answers. I interviewed philosophers, cartographers, librarians, academics, doctors, and game-makers; read books on digital life, as well as on philosophy, climate change, and the search for meaning; spoke with people who came of age online and have turned to digital communities to find belonging and a sense of self; attended a furry convention, an amateur drag show, and other spaces for exploring and sorting identity; and reflected on my own online life. Along the way, I encountered people using the internet to find meaning and connection—the things we’ve historically found offline in places like churches, mosques, and civic groups, but increasingly find online, in contexts of our design. And I also found that all this newness—the novel ways of being human that are emerging online—can teach us new things about age old questions concerning what it means to be human.

All of this resulted in a book, IRL, which I finished writing at the end of 2019. Just a few months later, the pandemic forced me and so many other people around the world to stay home and live even larger chunks of our lives on the internet. As we scrambled to move immensely important pieces of our lives online because we had no other choice, I was surprised that this journey which had begun for personal reasons—a desire to make sense of the tension I felt in my own online humanity—would be born into a world in which so many of us are now struggling with what it means to be a person online.

I didn’t know that the years I spent researching, reflecting, and wrestling with these questions would lead to a year in which they would be some of the defining questions of our lives. But in 2020, as I tried to make sense of a world in which the majority of my interactions were suddenly happening online not by choice but by necessity, I found myself returning again and again to what I learned from the people I spoke with for IRL, and to the still-live questions that drove me to write it.

Early on in the pandemic, I once again struggled with digital life. I spent hours scrolling through tweets and Instagram stories, comparing other people’s social media posts about quarantined lives in expansive houses with loved ones they could hug to my own experience fully isolated in a cramped studio apartment. I saw posts mourning cancelled vacations while I fretted about how I was going to pay rent as my income evaporated overnight. Or, perhaps most of all, I felt like everyone was zooming and FaceTiming and Skyping while I mostly went on long walks alone with my dog. But this, of course, was my own doing, because some part of me still felt like those things were “less real” than interacting offline.

But then I thought of Zain, someone I’d followed on Twitter for almost a decade but who, as it turned out, I actually knew little about. While working on the book, I decided to reach out to him and find out more about the person behind the account. As he filled in all the gaps of his complicated life, Zain taught me about the projecting we so often do onto other people’s digital blank spaces, and what we can come to understand about ourselves by asking why we do that—insights that were helpful any time I found myself comparing my own pandemic circumstances to the glimpses of other people’s lives I caught through social media. Whenever I started resenting that I had to connect primarily through digital means, feeling like I was just in a holding pattern until I could get back to “real life,” I thought about Merisa—someone else I met on Twitter, who shared her story of using the internet as a space to explore her identity as a trans woman both before and also long after coming out. Merisa helped me understand that the internet can allow us to explore ourselves in ways we can’t offline; that it’s not just a shadow we settle for until we can get to something more “real,” but a rich space for coming to know yourself better.

And when, in my most frustrated moments, I found myself dismissing the internet altogether and wanting to just completely disengage, I thought about the communities I spoke with who are organizing online, individuals who have used social media as a lifeline, and how investigating the ways we digitally map our lives presents us with unprecedented opportunities to ask ourselves questions about what we value and why. Any time I came up against one of the many challenges presented by digital life this year, and wanted to wave off my digital experiences as “less real” than what I can experience offline, I pushed myself to instead treat digital life in the way so many of the people I spoke with did, as a space rife with opportunity. To see it as containing just as much possibility for real, meaningful connection as life offline.

2020 hasn’t been easy for anyone. In a time of necessary social distancing, it’s easy to feel alone, and to look at digital life as a poor substitute for the “real life,” offline comforts that the pandemic has made rare. But then I remember what I learned from the last few years of inquiring into the opportunities the internet presents to reapproach what it means to be human, and all the moments the internet has helped me feel understood and connected, beginning all the way back when I first came out as queer to digital strangers in adolescence. Being human online isn’t always easy, but it does give us a chance to see ourselves in new ways—something that, in a time of immense chaos and change, feels not just valuable, but vital.

I’m still wrestling with how to feel human online, but working on this book gave me tools for the journey, like the tools a cartographer uses when setting out to map an unfamiliar territory, or a key for a door you haven’t yet opened. I hope the book can help others as they wrestle, too. That it can be a key for those in need of one, as it has been for me—one that came years before, for a door I had no clue was coming.

__________________________________

IRL by Chris Stedman is available via Broadleaf Books.