How to Deal with Rejection (and Get Revenge) Like Edgar Allan Poe

Catherine Baab-Muguira on Doubling Down on Your Ambitions

When Edgar Allan Poe was 17 years old, he and John Allan loaded up the family station wagon with all his clothes, posters, and books, and made the 70-mile trek west to Charlottesville, Virginia. Among the rolling hills of that town, Thomas Jefferson had recently founded a university meant to serve the sons of the state—at least, those sons who could afford to spend a few years drinking, gambling, goofing off, and, on occasion, attending the odd lecture, maybe sitting an exam or two. Poe saw his own place in these ranks, and longed to distinguish himself in this fresh social and academic setting.

He may have been glad to leave Richmond for other reasons, too. Poe’s teenage years had seen a certain tension crop up in his relationship with his foster father. Gone were the relative ease, affection, and approval—if not intimacy—of their relations when Poe was still a child. At some point, Poe probably learned of the illegitimate children that John Allan had fathered elsewhere in Richmond, which may have been what prompted Allan to insist that the rumors about Poe’s biological mother were true—that Eliza’s youngest child had been fathered by another man, not her husband.

Writing to Poe’s brother Henry in 1824, John Allan pointedly referred to Rosalie as “half your Sister,” adding piously, in case his point was somehow missed, “God forbid my dear Henry that We should visit upon the living the Errors & frailties of the dead.” In the same letter, he complained that Poe “does nothing & seems quite miserable, sulky & ill-tempered to all the Family.” John Allan was, it seems, beginning to resent his ward’s reliance on his charity—as in, how come this assetless teenage orphan just accepted everything he was given? Why couldn’t he pull himself up by his bootstraps like John Allan had? Sure, John Allan was, about this time, being bailed out of a tough spot by his wealthy uncle—whose fortune he would soon inherit—but even so, he had never enjoyed the kind of advantages Poe enjoyed. He had never had the chance to go to college.

If Poe relished his escape from these harangues, he may have also realized that he was being set up to fail. Before leaving him in Charlottesville in February of 1826, John Allan handed Poe just $110 (or so Poe would claim later). This when tuition and fees ran closer to $350.

You know how it goes. You’re on your own for the first time. You don’t want to admit how lost you are, don’t want to beg or turn back the way you came. And so, to cover the widening gap between your means and your expenses, you start to borrow. If there had been, in those days, credit-card company reps loitering outside the UVA student union with their quills and free waistcoats, Poe would have signed up on the spot.

As it was, he first cadged some credit from merchants in town, and when that proved not quite enough, he tossed back a couple of peach brandies and sat down at the poker table, cracking his knuckles and hoping for the best. After a few hands, he found himself in an even bigger hole, so he just kept on playing and losing, and losing, and losing, until he was $2,000 in hock—some $50,000 in today’s money.

Now he really couldn’t stay in Charlottesville. There was nothing for it but to trudge home, tail between his legs, creditors nipping at his heels.

John Allan gloated, hard, as bullies do. All he would offer Poe was an unpaid job in one of his offices. He refused to pay Poe’s debts, and when collection agents arrived at the ornate family manse, attempting to seize Poe’s possessions, they found there was nothing to repo—no TV, no Xbox, much less a Corolla. Foster father and foster son argued bitterly, and Poe decided to quit John Allan’s house before he was pushed, or perhaps as he was pushed. He left the manse, retreating to who knows where, and swearing to John Allan in a letter that he would find “some place in this wide world, where I will be treated—not as you have treated me.”

In this same kiss-off of a letter, Poe requested that John Allan send him some starting-out money, as well as his trunk and clothes. His foster father did not reply. The next day, Poe wrote again, his tone turning desperate. “I am in the greatest necessity, not having tasted food since Yesterday morning,” he admitted, abandoning his earlier bravado. “I have no where to sleep at night, but roam about the Streets —I am nearly exhausted…”

Poe saw his own place in these ranks, and longed to distinguish himself in this fresh social and academic setting.Once upon a time, rejection by one’s tribe was a literal death sentence. To be abandoned as an early human meant to starve, freeze, or face the wolves and tigers alone, whichever came first. Unsurprisingly, you and I still find it hard to take. Because social bonds are so necessary to our survival, all our systems evolved to recoil from rejection. We don’t just experience it in terms of mental, emotional, and psychological strife—though heaven knows we experience it in those ways fully enough—but as physical pain.

In fact, researchers have found that OTC drugs such as Tylenol can help to lessen this pain, as though being told to get out of your parents’ house were the same thing as a migraine or a strained hamstring. So profoundly does rejection affect us, so greatly do we fear it, that we even experience it secondhand—we can feel rejected vicariously. This is why you can’t look away from all those “try not to cringe” compilations on YouTube, and why reading Poe’s abject teenage pleas makes you want to clap his Collected Letters shut, toss the book out the window, and go swimming in a fishbowl of Chablis.

Our deep dread of rejection also accounts for why, according to numerous surveys, public speaking ranks as people’s number-one fear, ahead of snakes, spiders, heights, premature burial, and the Spanish Inquisition. Even now you may feel the clammy, phantom wood of some distant lectern beneath your palms as the senseless drivel pours, uncontrollably, from your gullet. Nothing focuses the mind like that kind of self-consciousness so awful, so severe you almost want to laugh at yourself alongside those laughing at you.

Yet all of us will face rejection at some point. No one is exempt, which makes it all the more important that you understand how to have the right response—that, no matter your age or exact situation, you harness the gut-searing motivation that rejection can provide you, and make an ardent resolution like Poe himself made. “If you determine to abandon me,” he ranted to Allan in another letter later that year, “I will be doubly ambitious, & the world shall hear of the son whom you have thought unworthy of your notice.”

Give up? Hell no. At this key turning point, Poe doubled down on his ambitions, because if he didn’t, then everything Allan believed about him—that he was an idler, a loser, good-for-nothing—would be true. But you don’t have to mirror Poe’s exact playbook, which involved hopping a ship from Richmond to Boston, Massachusetts, assuming an alias, and, while starving and struggling to find work, paying out of his own pocket to publish his first book of poems, Tamerlane. You just need to nail the larger moves, outlined below.

Step 1.

Decide on revenge-via-success

Revenge, in this age of AR-15s, may strike a scary note. What we speak of here is nothing so cheap and cowardly, but what Poe himself sought: revenge-via-success (i.e., showing them all). Whether you are reacting to a rejection by your parents, by a would-be prom date, by your first-choice college or grad school, or if you’ve been fired from a job or are experiencing a surprise divorce, now is the moment to become “doubly ambitious” and tackle the huge task of forcing the world to care about you, at last. It’s time to make your mark, to prove to your foster father and all the other dim bulbs in your hometown that you are the person you know yourself to be. Whatever you’d planned to do with your life before, expand the plan. Make your mission grander, more epic, so that an entire lifetime may be required to fulfill it.

This step, counterintuitively, is more about you and your self-respect than it is anything external. Revenge-via-success is something you do for you, a form of self-care.

You’re gifting yourself a huge sense of purpose at a moment when you might otherwise be floundering, rudderless. So screw your heart up tight. Suck in your breath. Swear to yourself that one day they—whoever “they” are—will rue the day they doubted you. Even if, like a good lapsed Catholic, you long to forgive and you wish good things for everyone no matter what they’ve done to you, be sure you nurse a little desire for revenge as well. It’ll keep you warm at night in your single bed at the hostel, in your cramped seat on the Bolt Bus, and during your overnight shift in the glass cage at the bodega. Poe would want you to, and, frankly, you’re going to need it.

Step 2.

Change addresses in a big way

Some folks stay where they are and try to mend the hurt. Don’t. Go! Leave! Embrace the impulse to run. The place where you’ve been rejected has become a psychic prison, and putting it in your rearview is as much as a spiritual step as a physical one—marking the beginning of your mythic antihero’s journey. The anthropologist Joseph Campbell identified such decisive departure as the outset of your unique, glorious destiny, a literal call to adventure. “The familiar life horizon has been outgrown,” Campbell wrote, “the old concepts, ideals, and emotional patterns no longer fit; the time for the passing of the threshold is at hand.”

Granted, you may think you can’t afford to pass the threshold. Of course you can’t. Few of us can. Do it anyway. Action beats planning. Just pull up stakes, whether that means moving to the nearest city from your rural county—ah, the bright lights of Topeka!—or to an actual big city on the coast, where every day you have to choose between rent and lunch. It hardly matters where. Fail to remove yourself from the scene of rejection and you’ll miss one of life’s great chances. You may be broke, yet a new world awaits you. What notions of spectacular vindication will you nourish? Your life is now either (a) spinning out of control or (b) taking a turn wilder and weirder than you ever deemed possible.

Think of those who’ve come before you and take heart. Generations of theater kids, queer kids, artists, intellectuals, freaks, and dissidents of all stripes have all left their hometowns for bigger arenas. Buddha did it, so did Jesus. Poe too. Why not you? Crucially, such a move will also free you to exaggerate how well you’re doing in the new location—perhaps even to convince some indifferent ex that you’re in an exciting new relationship when you are, uh, not. Lock down all the wins, friend—real or, you know, invented. You’re in charge of your own narrative now, and only you get to decide what’s fake news.

Take the Poe tip: If you find yourself rejected and humiliated, then adopt a fake name and flee town, ideally under cover of night. Return when, and only when, you’re rich, famous, and successful—or able to convincingly present yourself as such.

__________________________________

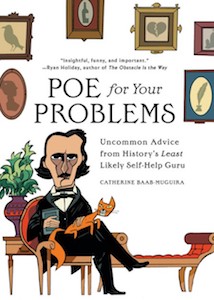

Excerpted from POE FOR YOUR PROBLEMS: Uncommon Advice from History’s Least Likely Self-Help Guru by Catherine Baab-Muguira. Copyright © 2021. Available from Running Press, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.