How to Build a Dictionary: On the Hard Art of Popular Lexicography

Ilan Stavans and Peter Gilliver Discuss the Philosophical and Pragmatic Aspects of the Oxford English Dictionary

At the end of the first quarter of the twenty-first century, about 400 million people are native English speakers. With those for whom English is a second language, the number reaches far above: between 1.5 billion and 2 billion. Linguist David Crystal believes the ratio of non-native to native English speakers is three to one. Needless to say, English is a challenging language, especially when it comes to spelling—in James Joyce’s words, it is “the most ingenious torture ever devised for sins committed in previous lives.”

This conversation concentrates on the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) as a Platonic model not only within the English language but in countless other linguistic ecosystems. It looks at Samuel Johnson as the cathartic figure whose lexicographic work shaped modern English dictionaries. And it ponders the sprawling OED products and compares the enterprise to its American counterpart, Merriam-Webster. In short, what follows might be called a creative exploration of—or a series of efflorescences from—the ways in which the pragmatic perspective of the practicing lexicographer differs from the philosopher’s ideal perspective.

*

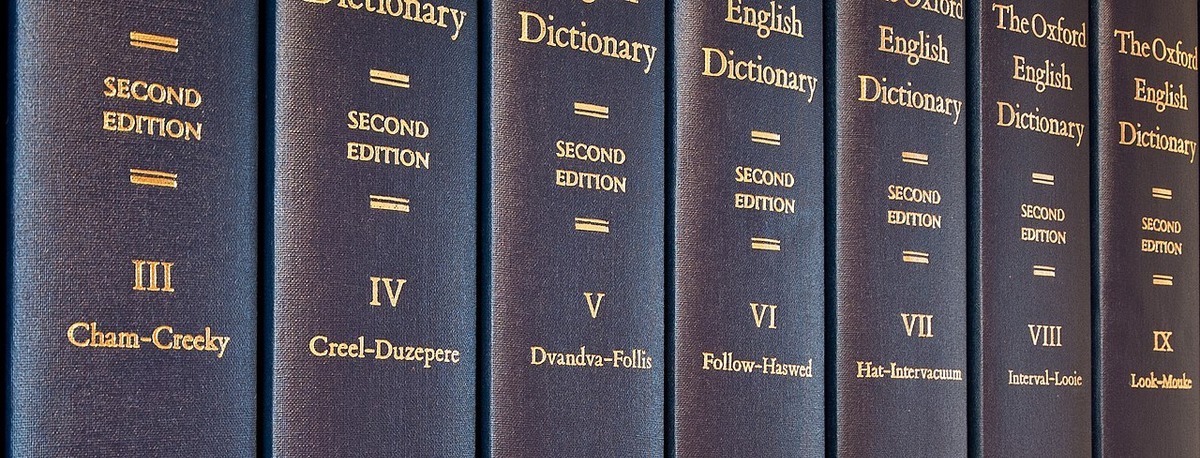

Ilan Stavans: The OED is the mother ship of lexicons. As an immigrant with limited means, I remember coming across with trepidation the two volume edition that came in a box with a small drawer containing a magnifying glass. I bought myself a copy after I saved a bit of money. Looking up a word was simultaneously arduous and thrilling: arduous because the font was so small, you had the impression you were involved in an archeological quest; and thrilling because the lexicon invariably gave you the impression it was “total,” meaning it had done everything in its power not to leave anything out, although, of course, this is impossible. You have been with the OED since 1987. I want to start with your family. Both your parents were linguists. Might you describe the role that studying, defining, and cataloging words played in your childhood household?

Peter Gilliver: Yes, we were a very “language-minded” family: there were often discussions about language and usage (mainly English but also occasionally German—I spent my childhood in Germany, where my father worked for the British Army as a language lecturer, and my mother taught English classes in local German schools).

The way in which the OED is authoritative…is a very different kind of “authoritativeness” from what many of today’s readers look for in a dictionary.

I can trace my interest in words as individual entities to, firstly, the family’s enjoyment of the TV panel game Call My Bluff—a version of the “Dictionary Game” in which celebrities tried to guess the meaning of obscure words picked from the pages of the OED—and, secondly, a school dictionary (I’ve never been able to track down which one) which I found strangely readable. (I seem to have a particular memory of the word chalazion; what such a rare word for a pimple was doing in a small children’s dictionary I can’t imagine, but it stuck in my mind.)

Perhaps this laid the groundwork for the “feel for words” which I think makes a good lexicographer; but I credit the “watering” of that “ground” to Mr. Emberton, one of my teachers at boarding school. I certainly took to Latin (which was his subject), but he also spotted—and fed—my interest in English words and wordplay. (I learned how to tackle the Times crossword at his elbow, something for which I remain eternally grateful to him.)

Also, at boarding school I did something which I think a fair number of language-minded children do: in collaboration with my best friend at school—a remarkable boy who had begun to learn ancient Egyptian in his early teens (and who has gone on to become a very distinguished Egyptologist)—I devised a language of my own, which involved compiling a dictionary of it. This may have been partly inspired, as I know it is for many people, by the invented languages to be found in J. R. R. Tolkien’s books, of which I (and he) was an admirer; certainly I’m not the only OED lexicographer who had a go at doing this.

Which is a bit of a hotchpotch of strands of influence; but I do think that some of those things contributed to my being a lexicographer.

IS: I like your use of parenthetical phrases, which dictionaries, of course, are precluded from doing. Anyway, in numerous cases in this volume, being aware of dictionaries in other languages has left a mark on lexicographers. Do you speak other languages? Do they serve as a “contrast” in the way you look at the development of English?

PG: I have a basic-to-decent knowledge of French and German, and Latin, and I can stagger by, on a tourist level, in one or two other Romance languages. I don’t have a solid familiarity with dictionaries of any language other than English. So, no, dictionaries of other languages haven’t had a significant influence on my relationship with the lexicography—or the history—of English. By the way, I don’t know what you mean about dictionaries not parenthesizing: in my book, a lexicographer should feel free to use whatever means may be necessary to describe the lexicon.

IS: Sometimes in the dead of night, in a bout of insomnia, I like to imagine how languages came to be. I think of Jorge Luis Borges’ story “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” (1940), about a fictional country where, like the materialist world in which we live, everything exists in ideal form. Borges tells us that in Tlön’s Ursprache there are no nouns; instead, there are impersonal verbs, modified by monosyllabic prefixes with an adverbial value. For instance, he argues that there is no word for “moon,” but there is a verb which in English would be “to moon” or “to moonate.” ‘The moon rose above the “river,”’ he says, “is hlor u fang axaxaxas mlo, or literally: ‘upward behind the onstreaming it mooned.’” Anyway, I enjoy imagining the dictionaries used in Tlön and wonder at what time they appeared in the development of the nation’s language.

Like French, Portuguese, and Spanish, among others, English is an imperial language. Is the appearance of an authoritative dictionary at a precise moment in the history of a language a statement about its maturity?

PG: Well now, this isn’t an interesting question I’ve ever given much thought to. (Another parenthesis: I’ve never read anything by Borges, but it strikes me as bizarre that he should envisage an ideal language as being one without nouns.) I’m afraid I will do what lexicographers do: query the word “authoritative.” The way in which the OED is authoritative—namely as an exhaustively documented historical record of the development of English lexis—is a very different kind of “authoritativeness” from what many of today’s readers look for in a dictionary: namely authoritative assertion about what is “correct” or “valid” in a language.

When I put it like that, I find myself wondering whether it’s actually not maturity in a language that is most conducive to the creation of authoritative texts (in the latter sense) about it, so much as insecurity about the state—and the status—of a language. It’s not hard to find, in writing about English in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, expressions of concern about linguistic disorder and decline, and—often in the same sources—advocacy of dictionaries as performing a welcome standardizing function.

And it’s my impression that many of the dictionaries that appeared in this period were a response, sometimes explicitly so, to this expression of a need for regulation/standardization. Johnson’s dictionary was, surely, one of these, certainly in its genesis (I’m thinking of Lord Chesterfield’s acclamation of Johnson as a fit “dictator” to establish that “lawful standard of our language” that he has long felt the lack of.)

But your question does suggest another, related question: How can we explain the appearance of particular dictionaries at particular points in time? I’m not enough of a Johnson scholar to be able to say just why Johnson’s dictionary appeared when it did, but could it perhaps be argued that its appearance—as the most masterfully “authoritative” response to his contemporaries’ desire for regulation/standardization—owes everything to Johnson being the man he was?

When it comes to the OED, on which I feel better qualified to comment, I think it’s pretty clear that there was “something in the air” in mid nineteenth-century Europe, which gave rise to not one but several projects to compile dictionaries of particular languages that were unprecedentedly historical in their approach: the Grimm brothers’ Deutsches Wörterbuch project, the Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal, and the New English Dictionary on Historical Principles, which we know better as the OED. When I wrote about this in my history of the OED, I argued that one of the “things in the air” was the Romantic conception of a language as the embodiment of a nation’s identity; I think the lexicographers of the time were moved to give this conception expression through what has come to be called the “historical principle”—the idea that (in the words of Franz Passow, who had done this for ancient Greek a few years earlier) a dictionary should tell “the life history of each individual word.”

Passow could hope to do this single-handedly for a language like ancient Greek, with its limited corpus; for modern languages the collection of the evidence from which these “life histories” could be told was a task too big for one individual, but one which could have the grand appeal of a “national” project. I put “national” in quotation marks because in the case of English the appeal reached beyond one nation to all corners of the English-speaking world—since that is the language which the New English Dictionary aspired to document. And today’s OED lexicographers are continuing that work.

IS: Passow’s lexicographic work, because it dealt with a limited corpus, was sharply focused. His Vermischte Schriften (1843) is a fascinating exploration of his method and affinities. He had an impact on James Murray. Anyway, Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language, to my mind, is the most astonishing of lexicons ever produced in any tongue. That a single man put it together almost alone is, in and of itself, a feat to reckon with. What have dictionaries lost in the process of becoming efforts done by committee?

PG: Johnson’s achievement is certainly prodigious (though I’m glad, for the sake of his assistants, that you put in that “almost”). I think it could be argued that Noah Webster’s achievement in compiling his 1828 dictionary “almost single-handedly” is also pretty impressive. And who else is there? Charles Richardson, compiler of another two-volume English dictionary in 1835-37? And I’m sure there are comparable figures in the lexicography of other languages (I find Émile Littré’s four-volume work pretty amazing, for example). But the size of the task of compiling a comprehensive dictionary–of English or any language with a comparably rich history—has now grown far beyond what a single individual could hope to achieve in a lifetime.

To be honest, I can’t help seeing the development from one-person dictionaries to team efforts more in terms of gains than losses: quite apart from the simple fact that the person-hours—or person-centuries—required to compile a dictionary like the OED make a collective approach essential; having a team means that you can be sure of having at your disposal more of the different kinds of expertise that the work needs. Yes, of course a dictionary that hasn’t been compiled by an individual may well be, well, less individual, less obviously showing the stamp of one person—though there are still all sorts of ways in which the guiding hand of a chief editor like James Murray can still be discerned in the OED’s character and policy and style (keen as he always was to stress its collective nature and to acknowledge the part played by his staff).

And indeed, if you know where to look, you can still find later English dictionaries compiled by an individual whose character strongly shines through its pages. Of course, there are works like Ambrose Bierce’s Devil’s Dictionary, but of course that’s not a dictionary in the usual sense; I was thinking more of H. C. Wyld’s Universal Dictionary of the English Language (1932), whose definitions are sometimes almost Johnsonianly idiosyncratic (like the famous bun “small round sweet spongy cake with convex top and too few currants”).

IS: I frequently go to the definition in the OED of “God”: “A superhuman person regarded as having power over nature and human fortunes; a deity (use in the singular usually refers to a being regarded as male (cf. goddess n.), but in the plural frequently used to refer to male and female beings collectively). Chiefly applied to the divinities of polytheistic systems; when applied to the Supreme Being of monotheistic belief, this sense becomes more or less modified.” And it goes on, of course. I find troublesome countless aspects of this definition. For starters, “a superhuman person”? Anyway, what is the longest entry in the OED? Is there a house limit for length?

PG: Well, it depends what you mean by “longest” (what a predictable response from a lexicographer). If we’re talking bytes, then at the moment it’s the entry for the verb run. (An entry which I happen to have first-hand experience of: I spent nine months revising it. In fact, I was only one part of the revision process, and others were working on it before and after me.) “At the moment” is a key qualifier here, though: the revision of the dictionary is ongoing, and every unrevised entry—which may have been originally written a century ago or more—becomes quite a bit larger when it’s revised.

This may be because an old word has acquired new meanings; but even a word which has remained semantically unchanged still needs—unless it’s become obsolete—to have the documentation of its existence extended, with additional quotations bringing the illustration of its history down to the present (or down to when it ceased to be used). So it’s possible that one of the bigger unrevised entries will overtake run when it’s revised. One obvious candidate is that for set (verb), which occupied more printed pages than any other entry in the first edition of the dictionary, longer than run.

However, I think this is unlikely: set feels to me like a verb whose time has passed—it’s not as common as it was, and it’s been less “active” in the last century (in the sense of throwing off new meanings and new uses) than run. So, yes, the entry will expand when it’s revised, mainly because the paragraph of quotations that accompanies the definition of every current sense of set will get longer, but I don’t think it will overtake run. Or take or go—these being the next two largest entries by bytes. Both are also revised entries for verbs. These “big verbs” certainly feel like the most challenging entries in the OED, in terms of stamina!

It’s worth saying, though, that for a lexicographer the “size” of an entry may be better gauged by a different yardstick: not the number of bytes but the number of components into which it’s divided. (These are how we measure out our progress on the OED; our quarterly and annual targets are set in terms of the number of components we get through.)

IS: It strikes me as meaningful that the OED is an academic endeavor based in the United Kingdom whereas Merriam-Webster is a commercial enterprise produced in America.

PG: I’m not quite sure where to go with this. Do you know the British expression “horses for courses”? Or “apples and oranges”? Some of the most important other dictionaries of English that are most like the OED—in being compiled on historical principles, with entries containing quotations illustrating each word’s history—have in fact emerged, or are emerging, from North American academic institutions: the Dictionary of American English, compiled in four volumes under the auspices of the University of Chicago (1938-44); the Middle English Dictionary, done by the University of Michigan (1952-2001, revision ongoing); and the Dictionary of Old English, by the University of Toronto, still in progress.

In some ways, I would argue that the closest British counterpart to Merriam-Webster’s “unabridged” is the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary: originally published in two volumes (like Noah Webster’s original and several later editions), with some historical focus but only a sprinkling of quotations. When Oxford University Press (OUP) was first approached about the possibility of publishing the Philological Society’s proposed big historical dictionary, in 1877, they were blandished with the claim that they would be investing in “what promises to be a very safe and remunerative [undertaking].”

The size of the task of compiling a comprehensive dictionary…has now grown far beyond what a single individual could hope to achieve in a lifetime.

This of course proved not to be the case—the first edition of the OED was to cost OUP hundreds of thousands of pounds, and the Press’s investment in the ongoing revision program now runs into millions—but even after OUP reconciled itself to this, it was recognized from very early on that shorter abridgements of the dictionary could be profitable. And this was to prove to be the case: I believe the Concise Oxford Dictionary was a runaway commercial success from its first publication in 1911, and by the 1970s, sales of the Concise and other smaller dictionaries were bringing in millions of pounds a year.

IS: Profit—this makes me think of the internet as today’s default habitat of dictionaries. What I mean is that many more users seek words online than in a physical copy of the dictionary. Is the age of the printed dictionary coming to an end?

PG: I’m sure it must be the case that many, many fewer print dictionaries are sold now than was the case even a few years ago. And it’s hard to see how the ready accessibility over the internet, mainly for free, of information that once was only available in a print dictionary is going to go away. Which implies that, yes, the age of the print dictionary must be passing. That being said, dictionaries have always served many different purposes…and the question I would ask is, out of all of the different purposes which a dictionary can serve, are all of them now served better by online dictionaries than by print ones?

I don’t know enough about the state of dictionary publishing to answer that—I’m a lexicographer, not a dictionary publisher—but my guess would be that there may be some use cases that are still well enough met by a print dictionary for it still to be commercially worthwhile to produce one. Most likely in contexts where access to the internet is most constrained.

IS: How has lexicography changed since you became a lexicographer?

PG: On the one hand, enormously; on the other, very little. When I started work on the OED, our lexicography was pretty well entirely paper-based, and almost all aspects of the work would have been recognizable to James Murray and the other compilers of the first edition. The evidence to be considered when drafting a dictionary entry for a new word or meaning—and I started as a new words editor—was all in the form of 6-inch-by-4-inch slips of paper, mostly handwritten; it’s true that we supplemented the quotations that had been collected by the dictionary’s paid and volunteer readers by checking in some computer-generated concordances of particular texts, but we did so by writing out more quotations on more slips.

The end result was a bundle of slips: a chronologically ordered selection of quotations illustrating the word, topped by a “top slip” bearing my draft definition, pronunciation, etymology, etc. Exactly what Murray or his assistants would have produced (although our bundles would then go off to be keyed into a database, rather than being typeset by compositors). There was no computer on my desk. There was a computer in the basement, hooked up to a modem, by means of which we could get “on-line” (it was hyphenated in those days) to some of the early searchable databases of text; but any database searches would be printed out and added to the bundle of slips.

Until the start of the 2020s, I would have said that on almost every OED lexicographer’s desk there would still be some of those same paper slips; but they are rarer now (the inaccessibility of our paper files during the worst days of the pandemic probably contributed to that decline). The evidence we set about assessing when working out what needs to be said about a word is now almost entirely electronic; and we have access to more of that evidence, and more sophisticated access to it, than our predecessors could have dreamed of.

Not only can we summon up, with just a few keystrokes, every instance of a word to be found in any of dozens of databases of historical and contemporary text—from corpora of Middle and Early Modern English to X/Twitter, focusing on particular regions of the English-speaking world more or less at will—but we can also analyze the behavior of the word within these domains, using powerful text-crunching software that can tell us things like the most common objects of a particular verb, or the most typical nouns to which a particular adjective may be applied.

Instead of merely wondering whether a word or meaning may have originated in, say, the southern United States—perhaps prompted by the fact that that’s where the earliest quotation slips come from—and maybe sending a library researcher on an almost-hopeless search for earlier examples in particular printed sources, a few searches of newspaper databases can take us almost to the smoking gun: yes, that word can first be found in Texas in the 1840s. Or it first came into general use among Freemasons in the late eighteenth century. Or among Australian speedway enthusiasts in the 1990s.

Often (though not always!) we can get closer to giving a definitive answer to the question “where does that word come from?” than we ever could before these amazing resources became available. This wealth of information can be a double-edged sword, though: I often liken it to having developed a far too acute sense of hearing—the “noise,” in various senses of the word, can be deafening.

And anyway: though the tools may have changed, what we are doing with them hasn’t. The lexicographers of the first edition of the OED—and, indeed, earlier lexicographers like Johnson—would recognize and understand the process as, essentially, the same as what they were doing: surveying the available data about how a word has been used, over time, and distilling this data into as accurate and comprehensive a historical account as we can manage. Analysis of the evidence, synthesis of that analysis. Because that’s the right way to do lexicography. My kind of lexicography, anyway. That’s what I meant by “very little has changed.”

*

This exchange is part of Conversations on Dictionaries: The Universe in a Book (Cambridge University Press), by Ilan Stavans, due out in September. It features twenty-two conversations with the top authorities on dictionaries in twenty-two different languages: from Arabic, Esperanto, French, and Ancient Greek to and Japanese, Italian, Nahuatl, Spanish, and Yiddish.

Ilan Stavans is Lewis-Sebring Professor of Humanities and Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College, the publisher of Restless Books, and a consultant to the Oxford English Dictionary.

Peter Gilliver is an executive editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, where has been working for nearly forty years. He is the author of The Making of the Oxford English Dictionary (2016).

__________________________________

From Conversations on Dictionaries: The Universe in a Book, edited by Ilan Stavans. Copyright © 2025. Available from Cambridge University Press.

Ilan Stavans

Ilan Stavans is the Publisher of Restless Books and the Lewis-Sebring Professor in Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College. He is the recipient of numerous awards and honors, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, Chile’s Presidential Medal, and the Jewish Book Award. Stavans’s work, translated into a dozen languages, has been adapted to the stage and screen. He hosted the syndicated PBS television show Conversations with Ilan Stavans. He is a cofounder of the Great Books Summer Program at Amherst, Stanford, and Oxford.