It is a question of time’s long reach. In many African countries the main period of colonization occurred between the late 19th and mid 20th centuries. The foundational assumptions about Africans, however, had been made centuries earlier. Say, for instance, in the records of Balthasar Springer, a German merchant who had traveled in 1506 along the Atlantic Coast on a Portuguese ship, around the Cape of Good Hope. Two years later, Hans Burgkmair the Elder—an artist who lived in Augsburg, then the German center of imperial politics—set out to illustrate those travels on six woodcuts. One resulting drawing by Burgkmair is, as described in the British Museum, of a “standing black youth dressed in a feather skirt, cape, and head-dress and holding a club and shield.” “Let us imagine,” writes V. Y. Mudimbe regarding Burgkmair’s drawings in The Invention of Africa, “the painter at work.” Mudimbe continues:

He has just read Springer’s description of his voyage, and, possibly on the basis of some sketches, he is trying to create an image of blacks in “Gennea.” Perhaps he has decided to use a model, presumably white but strongly built. The painter is staring at the pale body, imagining schemes to transform it into a black entity. The model has become a mirror through which the painter evaluates how the norms of similitude and his own creativity would impart both a human identity and a racial difference to his canvas.

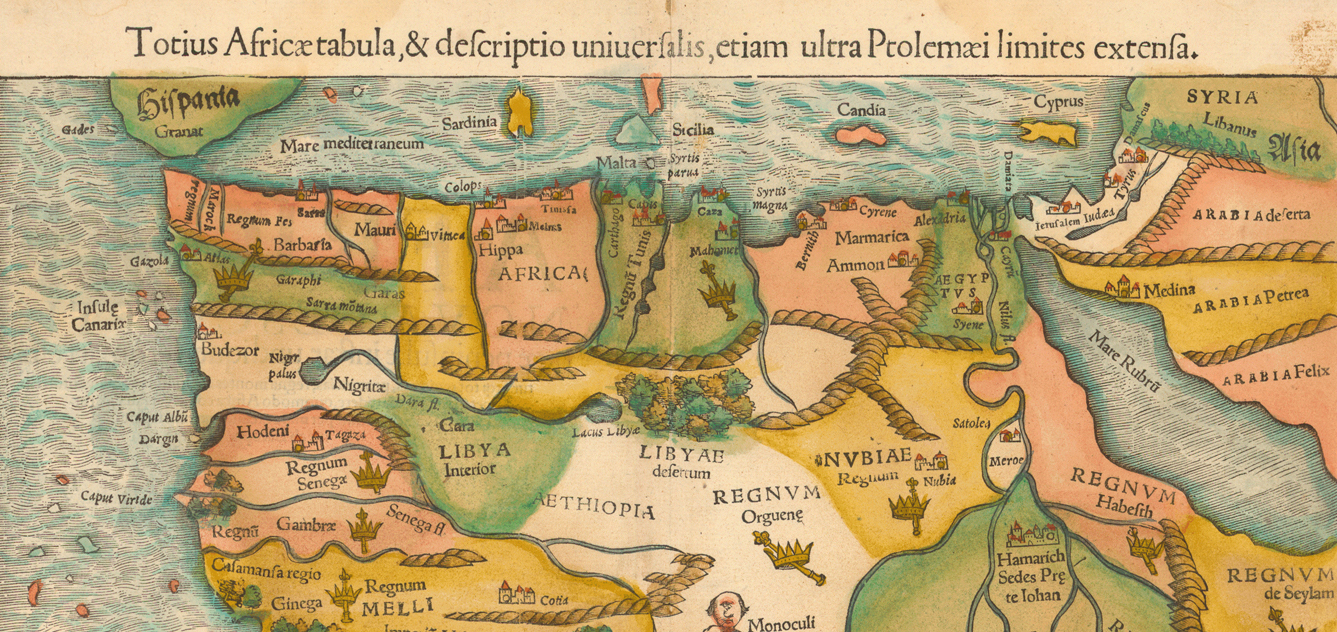

This assumption—that by projecting blackness against whiteness you can define it—became not just foundational, but functional, a matter of form (colonialism is from Latin colere, meaning to cultivate or to design). As the explorers and merchants began to return with stories from terra incognita, their empires had a basis with which to pursue their work of imposing colonies. Once the hinterlands could be accessed, anthropologists sought scientific methods to classify the now indistinct Other. Perhaps this delineation is sweeping, yet it helps me begin: What are the broad historical strokes with which to account for travel writing in Africa? What is the shape the genre takes, whether in the writing of Europeans or in those by Africans themselves? How do I pay homage to a tainted genre, making a cursory, even if informed literary chart?

I begin in 1904, during the golden age of colonialism. The text of a book by Isabelle Eberhardt—which she referred to as her “Sud-Oranais stories,” titled Dans l’ombre chaude de l’Islam by her friend and executor—is discovered in an urn after her tragic death. The stories are of her Saharan adventures, from May 1904 onwards, when she leaves Ain Sefra, Algeria, “so much the little capital of the Oranian desert, solitary in its sandy valley, between the monotonous immensity of the high plateaux and the southern furnace.” The sense of a journey inwards is clear from the outset, and elicits deep feeling. She is less attracted to the idyllic Algerian desert or inclined to denote how her life differs from the Muslims she encounters. Hers is an introspective journey: “For me it seems that by advancing into unknown territories, I enter into my life.”

Her romantic notions are obvious in In the Shadow of Islam, but she had previously covered self-exploratory ground. Her mother, with whom she converted to Islam in 1897, had eloped to Switzerland with Alexander Trophimowsky, a former Russian Orthodox priest turned anarchist. Daughter and mother later moved to Tunis. Such remarkable, dramatic turns characterized her life—and, it seems, produced in her ambivalence about permanence, or home. “Once more astounded by all the that has captured me and all I have left, I tell myself that love is a worry and that what’s necessary is to love to leave—persons and things being loveliest when left behind,” she wrote.

Yet self-exploration, such as Eberhardt’s, occurs within a given place, at a given time. The quietude of a place, a journey that stretches unencumbered, the road that beckons: she couldn’t afford this in middle-class, cosmopolitan Geneva. What is it about the Algerian desert that makes the European imagination leap in wonder and rapture, in expectation for a near-religious experience, however genuine and therapeutic those sentiments? I look for clues in Michel Leiris’s Phantom Africa, a 700-page book first published in 1930, and reissued in a 2017 translation by Brent Hayes Edwards.

Leiris’s approach, as he writes in a foreword to the 1981 edition, “was not to conform to the picturesque standards of the classic travel narrative, but instead to scrupulously keep a travel notebook.” He’d earlier described the book as a diary. Leiris had been part of “Mission Ethnographique et Linguistique Dakar–Djibouti,” a momentous ethnographic project between May 1931 and February 1933, whose main task was to gather African art and artifacts for the collections of the Muséum National d’Histoire naturelle and the Musée d’ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris. Their trajectory encompassed most of the European colonies—along today’s Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso, Benin, Niger, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, Nigeria, Egypt, Sudan, Djibouti, as well as independent Ethiopia.

Leiris, barely 30 at the time, ventured afield with certain illusions—he hoped for self-transformation, and was ready to take in “exotic impressions,” as he wrote to his wife Zethe. He had no training as an anthropologist, although he would return to author a number of ethnographic studies. He was a writer disenchanted with Parisian literary circles, and a young man who, before the trip, was so plagued by anxiety and depression he had to consult a psychoanalyst. Hence, like Eberhardt’s, his was an exploratory trip in which he hoped to bring his inner self into focus. Yet, on February 15, 1932, after several months of journeying, he wrote: “The voyage only alters us for brief moments. Most of the time you remain sadly the same as you’ve always been.”

In his introduction, Brent Hayes Edwards suggests that the book can be read as a “painfully drawn-out and fitful chronicle of disillusionment.” From what illusion does Leiris recover? He achieves a remarkable fit of regimen, recording, day after day, his shifting emotional states on a journey that brought him in direct contact with the absurdity of the Mission Dakar-Djibouti—which, while claiming to see something of value in the artifacts that were collected, treated the cultures that produced them as inferior, unworthy of preserving their art. He became, in his own words, “disappointed by ethnography.” It was tedious, bureaucratic work. Only later, after a few decades, would he take an anticolonial stance, calling on fellow ethnographers to defend the aspirations of the societies they studied. On that trip however, writes Edwards, he produced, “an onrushing current of undigested everyday effluvia, rather than a reflection on the significance of the voyage, carefully crafted from the privileged vantage of hindsight.”

There are those, then, who write about their travels to Africa from the vantage of hindsight. Few years before his death, Ryszard Kapuściński described his life-work as “literary reportage” in a collection of lectures titled The Other, his final book. It can be read as the culmination of years of confronting people who do not look like him: In one lecture, delivered in Graz, while attempting to identify the features of “my Other,” he begins with skin color: “How often in Uganda I was touched by children who went on looking at their fingers for a long time to see if they had gone white!”

Kapuściński had first traveled to the continent in 1957, to Ghana, just as it became independent. He was a Polish journalist reporting for a state-owned newspaper. Unlike Leiris he didn’t seem to begrudge the tedium of his job. In fact, he was known, as noted by The Washington Post in a review of The Shadow of the Sun, his collected writing on Africa, to veer “into abrupt flights of lyricism on unexpected subjects.” His enquiry into Africa isn’t a travelogue per se, only the account of someone who traveled extensively within it. But he is a starting point for my enquiry into Paul Theroux, another acclaimed writer who wrote about Africa.

“I do not believe that I should have to deal with a lengthier process to visit a non-African country, when I do not nearly care as much to be there as I do to be in African countries.”Theroux’s two books of travel writing include “safari” in their titles: Dark Star Safari: Overland from Cairo to Cape Town and The Last Train to Zona Verde: My Ultimate African Safari. Admittedly, the word comes from root safar, Swahili by way of Arabic, meaning “journey.” Yet I am curious about Theroux’s reiterated use, given the unresolved ethical problems posed by safaris, which today commonly refers to expeditions in the East African wild.

Consider these passages:

And finally, the most important discovery—the people. The locals. How they fit this landscape, this light, these smells. How they are one with them. How man and environment are bound in an indissoluble, complementary, and harmonious whole. I am struck by how firmly each race is grounded in the terrain in which it lives, in its climate.

Happy again, back in Africa, the kingdom of light, I was stamping out a new path, on foot in this ancient landscape… I was ducking among thornbushes with slender, golden-skinned people who were the earth’s oldest folk, boasting a traceable lineage to the dark backward and abysm of time in the Upper Pleistocene…

The first passage is from Kapuściński’s The Shadow of the Sun, and the second from Theroux’s The Last Train to Zona Verde, both in the first chapters. These are trips in which the landscape is ancient, a new path is stamped out, and in which the protagonist encounters people grounded in the past. Hence the perennial problem is posed afresh: why is Africa always in need of discovery? And suppose it is true, that the earth’s oldest folk need reminding of their pre-historic claim to the earth, whose right is it, and who has the credentials to write that story?

I approach those questions—especially since I admire Kapuściński’s “flights of lyricism”—cautious of their complexity. I do not believe that only Africans should write stories about life in Africa, just as it is facetious to imagine Europe written about only by Europeans. The argument can devolve at once into a slippery slope. It seems to me that those who do not claim an African country as their place of origin enrich African writing, but only as far as they do not assume that a distance in worldview can be bridged by a single, or series of visits.

In this regard I acknowledge Anna Badkhen, an American writer. Hers is a multi-hyphenate genre: immersive-investigative-literary-journalism-as-travel-writing. After each of her journeys she returns with deeply involved, self-effacing narratives of permeable boundaries—between land and sea, humans and cattle, myth and truth, storyteller and story. In Fisherman’s Blues: A West African Community at Sea, she writes of fishing people who live south of Dakar, detailing their travails, deaths, and broken pirogues, as they face the dilemma of making a living like their ancestors, while confronted by the reality of a sea in ecological distress. In Walking with Abel: Journeys with the Nomads of the African Savannah, she accompanies the largest surviving group of nomads on the planet during their annual migration across the West African Sahel. Her books teach travel writing as a meditation on the borderline.

*

As an African writer, I contend with an idea that seems incontrovertible: my writing exists in the wake of derogatory narratives, therefore postcolonial. The damage has been done. Travel writing, by a Nigerian who travels in parts of Africa, is therefore a means of repair, a way to participate in a genre that historically speaks for—rather than with, or even to—me. While writing A Stranger’s Pose, my book of travel stories, I was attempting to situate it within a broad, mongrel genre. If a book by an African author conveyed the sense of a journey, or if travel across the continent informed the writing of a book, I included it in my portfolio of influences.

One literary forebear is Amos Tutuola. Consider My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, his second novel to be published, a lodestar in his constellation of tales about humans in a supernatural world. As a kind of travelogue, the book’s episodes are bookended by departure and return. I recognize its themes as those associated with the experience of travel—a distinct sense of home, an awareness of being estranged, the peculiarity of encounters with strangers, and upon return, a feeling of nostalgia for the foreign land visited. Put squarely, to read the book is to encounter yourself as a stranger. In one sense you are a stranger who relates to the disoriented feeling of the protagonist, a human among non-humans. In another sense, you are the unnamed protagonist, traveling through a foreign land, constantly at the verge of despair. The episodes are the dazzling flashpoints of years that elude enumeration. Indeed the novel is not entirely without chronology—in the Bush of Ghosts the protagonist becomes old enough to get married and have a son—but since he entered “unnoticed,” too young to know that “it was a dreadful bush or it was banned to be entered into by any earthly person,” his travails take on the character of those of a wanderer who, to survive, must surrender to the unpredictable vagaries of the journey.

Tutuola’s metaphysical world, rendered in bastardized English prose, turns me to The Sahara Testaments, in which the encounters are as acute and revelatory. It’s a magisterial collection of poems by Tade Ipadeola, his reflection on the Sahara Desert and its outlying countries in hundreds of quatrains—

…I did not ask her name, I wouldn’t pit

My halting French against her effortless river

Of Bambara and market French. I forget

What the fish tasted like but not the fever

Of curiosity, flaring as it did from a nugget

Of ivory that blinded my wandering eyes…

Yvonne Owuor is as evocative when writing about Lingala. She’s one of 14 writers who participated in The Pilgrimages Project, sent to one of 13 cities in Africa, and one in Brazil. Co-organized by Chimurenga magazine, the 2010 World Cup was a backdrop against which the writers were to produce travel narratives, and tales about their host cities. Owuor is a Kenyan in Kinshasa whose writing reads like an attempt to stay within a gap, one between resident and visitor. She is writing, as her title states, “In the Clear Light of Song and Silence.” More importantly, hers is a model exercise in emotional acuity while observing as a stranger: “The thing about Lingala is the inner knowing that pops up on first encounter—that this too comes from a deep, deep song, comes from the time when words had not broken off from music and perhaps the same time when humankind had not been infected by pain. It rouses new and old feelings with names yet unknown, certainly. Its chords vibrate and find resonance with something within, and I know, if I were of this place, in order to channel the sensations I too would need to sing or dance or cry.”

Though less lyrical, Zukiswa Wanner’s Hardly Working: A Travel Memoir of Sorts is also an account of a trans-African journeying, from Kenya via South Africa to Uganda, with her partner and son. She was born to a South African father and a Zimbabwean mother two weeks after 1976 Soweto Uprising, and nicknamed “Soweto” by the nurses. In her prologue she writes of her difficulties in obtaining a visa to Britain, just as her partner, a Kenyan man, had been attended with trouble while applying for a South African visa. She is decidedly pan-African: “I do not believe that I should have to deal with a lengthier process to visit a non-African country, when I do not nearly care as much to be there as I do to be in African countries.” This declaration, and by extension her multi-country road trip, is an unequivocal indication of the narrative landscape being mapped by African writers. The gaze is inwards, and continental.

Yet it is not a sweeping gaze—an attempt, however tenuous, to find what’s familiar in the diverse and unrelatable. In Looking for Transwonderland: Travels in Nigeria, Noo Saro-Wiwa writes of estrangement: “I had arrived in a country I had never lived in, and a city I’d visited only briefly twice before, among a thoroughly foreign-sounding people. It was the most alienating of homecomings. I might as well have arrived in the Congo.” Even then, she was doubly estranged: a dictator had murdered her father, the writer Ken Saro-Wiwa, and the country was “an unpiloted juggernaut of pain… a repository for…f ears and disappointments.” Part-returnee, part-tourist, with the innocence of an outsider, as she designates herself, she traveled in a country to which she couldn’t lay total claim, but which she was inclined to write about. At the end of her journey she was prepared, she writes, “to embrace the irritations with tentative arms, and invest some of myself.”

Two years before Saro-Wiwa’s travel account was published, Pelu Awofeso, a Nigerian journalist, had documented his own travels in Tour of Duty: Journeys Around Nigeria, writing with enthusiasm and patriotic flair. He was surprised to see, once while attending a Durbar Festival, merry tourists attracted to the spectacle. “Could this be happening in the same Nigeria often labelled as a no-go area?” He wanted to “push Nigeria some notches up the perception ladder of the world.” Written in tour-guide lingo, Awofeso’s adulatory prose seems intended to affirm a country as his, seeing something else besides the blights of successive years of maladministration.

These reflections on travels by Saro-Wiwa and Awofeso in their homeland are aptly postcolonial, a way to transcend and go beyond the legacies of colonialism. They could be read as a process, in the first place, of discovering the scope of the colonial effort, in which otherwise unrelated people were forcefully amalgamated. Nigeria’s Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka had undertaken a similar trans-national trip around 1960, the year of Nigeria’s Independence. He traveled around the country in a Land Rover, with a tape-recorder and a camera, sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation, who expected him to write a book on drama. The book was never written, but the experience, one could argue, informed his 1965 play The Road. “Breathe like the road. Be the road,” a character says at the end. “Spread a broad sheet for death with the length and the time of the sun between you until the one face multiplies…”

Journeys are so, a multiplication of faces, a means of relating to a wider world. Such as in Teju Cole’s Blind Spot, a book in which the Nigerian-American author pairs photographs and texts to reveal an atlas of a borderless world—Brazzaville, Brooklyn, Baalbek, Beirut, Fort Worth, Rivaz… “Why do I feel like I have seen him before?” He writes of a photograph in which a man’s back is to the viewer. “Marker says remembering is not the opposite of forgetting but rather its lining. Imagine, for a moment, that every face you cannot see is your own face, but years later. The future is lined with your future face.” Chris Marker himself, in his 1986 essay film Sans Soleil, had spoken of his time in Guinea Bissau: “It was in the marketplaces of Bissau and Cape Verde that I could stare at them again with equality: I see her, she saw me, she knows that I see her, she drops me her glance, but just at an angle where it is still possible to act as though it was not addressed to me…”

A Stranger’s Pose is framed by glances, addressed to those who do not see me, and to others I do not see. At the beginning, I watch from a car window as men walk to their houses, and at the end, I imagine a stranger glancing at the grave of a close relative, preserving her memory in the process. The journey ends. But images and gestures, remembered or imagined, return in great detail.

![]()

Emmanuel Iduma’s latest, A Stranger’s Pose, is available from Cassava Republic.