How the Writer Edits: Julian Barnes

John Freeman Talks Shop with the Prolific Novelist

With each new book, the size and scale of Julian Barnes’ curiosities continue to grow.

As he begins his seventies, they show no sign of diminishment. Barnes won the Man Booker Prize five years ago for The Sense of Ending, the tale of a man looking back on a botched moment of youth, but to begin reading Barnes here might be misleading.

He has written novels about aviators and detectives, Flaubert and theme-park life, short stories about aging, riffs on life in the kitchen, journalism about French politics, translations of the great diarist Alphonse Daudet, dozens of expertly argued reviews of modern art, tales of sex and revenge, and—for a brief period—a mystery series under the name Dan Kavanagh.

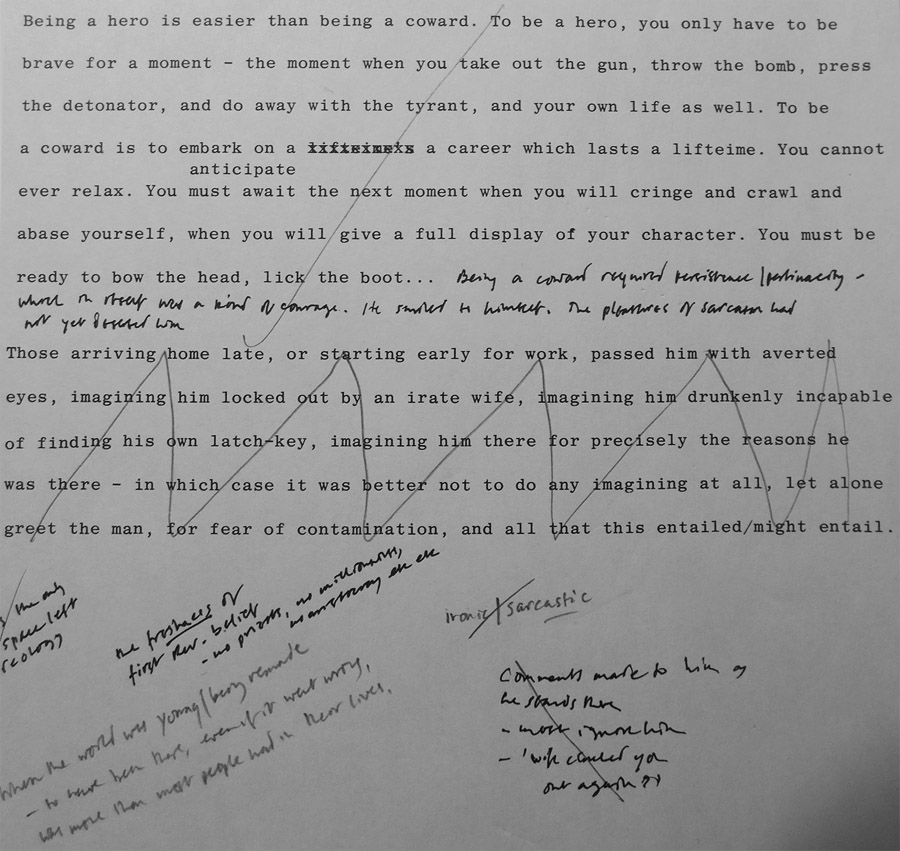

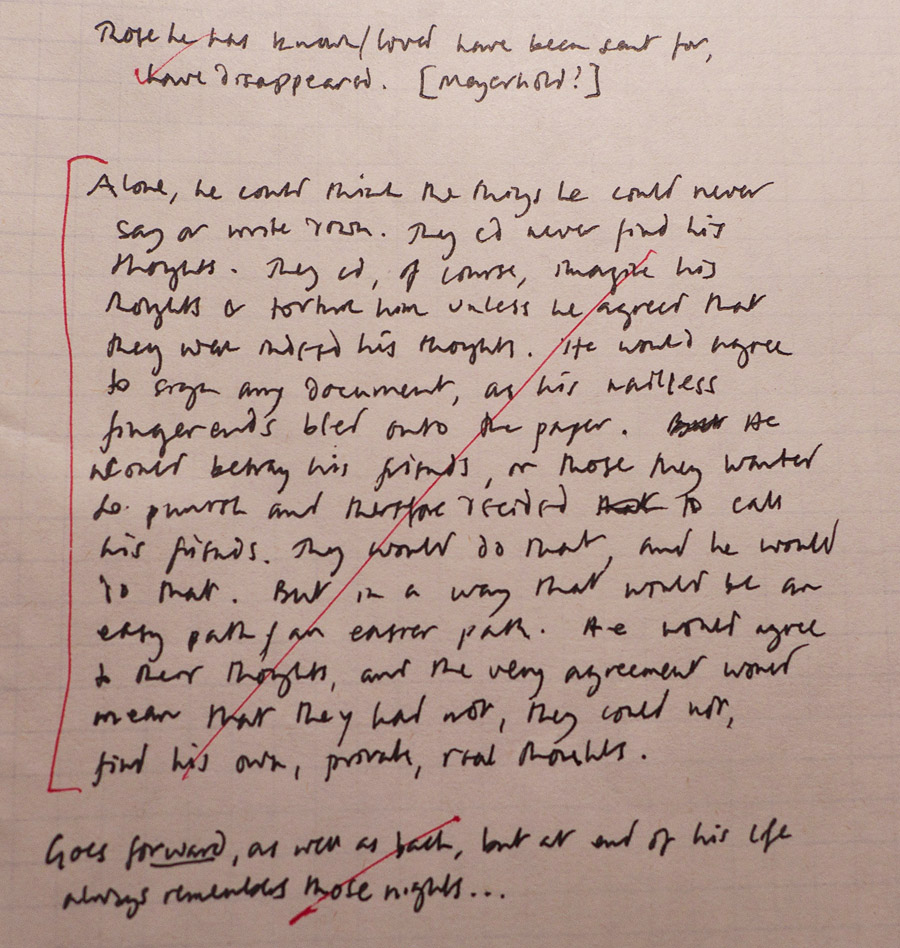

Barnes’s latest novel expands the territory even further. The Noise of Time is a harrowing, swift novel about the composer Dmitri Shostakovich and his attempt to compose music under Stalin. The book begins with the agonized Dmitri smoking a cigarette outside his apartment door, so terrified of the knock in the night he begins sleeping with his clothes on. And then not sleeping at all, just waiting in the hall. He doesn’t want to wake his wife.

In the next 200 pages Barnes depicts the many bargains Shostakovich had to make to stay alive, showing what these exchanges cost him emotionally and artistically. Like Barnes’s brief 1991 novel, Porcupine, set inside a collapsing communist country, it is a work of devastating mastery and mimicry. It feels as like a manuscript unearthed from the period, suppressed for the way it sheds a light on the corrosive degradations of Stalin’s power.

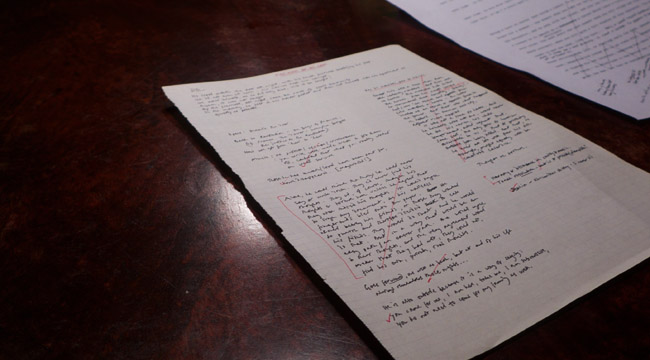

Sitting in his North London home, articulate and dressed in winter corduroy, Barnes—who began his writing life as a lexicographer—explained how he achieves such effects. He talked about what false starts occurred before he found the right tone to bring Shostakovich’s terrible inner life into sharp view, and not surprisingly, it all came down to choosing the right words.

Julian Barnes: I tried writing it in the first person, I wrote about four pages about a man standing outside the apartment, in the first person, and I just stopped. I didn’t know why it wasn’t working, it just wasn’t working at all, and I had just done it in the wrong person. I went back to it about nine months later, and started in the third person.

John Freeman: Had you ever done that, changed something from first to third person narration?

JB: No, I think it’s true that with each new book, you make new mistakes. So this bit for example, it started with a line of Flaubert’s, which says modern life has no heroes and no monsters and literature should therefore have no heroes and no monsters, and so the book began with a riff that the monsters had come back, and the monsters had killed all the heroes, so we live in a world that is monster full, and hero free. But I eventually scrapped it because it was too declamatory, it was too un-novelistic. You start off with different possible tonalities and the right one only gradually comes into play.

JF: Did you structure the novel like a symphony on purpose?

JB: I don’t really think so. The book has certain musical qualities in repetition and motif. But I do think musical form is different from literary form. That’s not how words work. There is a process, and there is musicality. You can have repetition of motifs, and you can build a theme, but they don’t really overlap seamlessly, as music does. I mean, you could say there’s a slow introduction to my novel, and then here comes the first movement. But I never thought I was writing a musical novel.

JF: Yes, even though he’s a musician.

JB: Yes, even though he’s a composer. This is often how I do write, with recurring motifs and phrases. And that’s a way of building up the structure.

JF: Style is a carrier for everything in a way?

JB: Well, I think in a novel which is sort of historical and biographical, as well as fictional, it’s my view—my view because it fits not just my aesthetic but also my interest—that you evoke the spirit best through the style, through the use of phrases, the oddities of phrases, which read at times a little bit like a translation. The noise was loud enough to knock out windowpanes is a sort of translation from the Russian, leaving it awkward. We’d say blow out windows, something like that, but “knock out windowpanes.” That for me gives the reader a sense of time and place and difference. I guess I’m also not terribly interested in “he walked down such and such street, and turned left, and there opposite him he saw the famous old confectionery shop or whatever.” I don’t do that way of creating the time and place and atmosphere. I think it’s much better done through the prose.

JF: I think in Arthur and George you use the word cockstand.

JB: Yes, which still exists.

JF: And I kept finding throughout this book words that felt as if they were translated from a Lermontov novel.

JB: Yes, there’s a bit of that. There’s a phrase that Russia is the homeland of elephants. That’s authentically Russian–and I think it’s completely wonderful. And there are things like playing fourhanded piano. Now we would say four-handed duets, but the Russians say playing four handed piano. Everyone reading knows what it is, it’s quite clear what it means, but it’s just a slight bit off from normal phrasing, and you think, ‘Yes, I am in Russia now.’ At least that’s what I hope you feel.

JF: Was working on Shostakovich different than other historical figures you’ve had in novels?

JB: Yes. I suppose the main thing was that although I did Russian at school for two years and two terms at university, my Russian is very, very dormant. My French is good, is pretty good, so I didn’t have any problem with Flaubert’s Parrot, and for Arthur and George, all of the stuff is in English. To a certain extent, with Shostakovich I was limited by what had come out in English. But I also had great help from Elizabeth Wilson, who’s the leading Anglophone Shostakovich expert. And she would send me letters she’d discovered, and I’d find a phrase in it or something like that.

JF: He’s quite possessed with self-loathing.

JB: Yes, I think he was, by the end of his life, a broken man. And he was broken by the state. In a way, he did come to think that he lived too long and should have died earlier. As it says at the start of part three, “the most dangerous time is not the time of greatest danger.” They come for his soul. In a way, my reading of him is that by then end, he can’t wait to be dead so it will just be his music. So he won’t have to deal with this awkward thing called life, let alone this dreadful thing called politics and power. And the music will escape the social circumstances it came out of.

JF: Do you feel any sympathy with him as a writer? Obviously the circumstances…

JB: Oh, I feel huge sympathy with him. I think he’s a hero, in the sense that he survived, he did all he could to help others, to protect his family. He was quite good at asking the state and the authority for help for others, but he couldn’t do it for himself.

JF: Yes he wrote a lot of letters it sounds like on other people’s behalf.

JB: Yes, and he was put in an impossible position. My friend Ian McEwan read the book and he said, “I hadn’t realized how much care they took of music and composers.” “Care” was used slightly ironically, in the sense of “close attention.” You think that they would go after more obvious dissidents or people who were against their system—well they did that as well—they were just in charge of everything. So there were really two solutions: one, to be completely silent and not write any music, and the other was to protest in such a way that you got sent to a labor camp and then your family would also be sent away to labor camp. So being a hero sounds attractive until you realize that being a hero involves the sacrifice of your friends and family. When you write about someone like Shostakovich, you realize what a comparatively cushy life you have as a writer in the West, unless you talk back to Putin or something like that. I mean I wouldn’t be a Russian novelist writing a satirical novel about Putin. I think you would probably end up dead on some bridge.

JF: I love these last five books of yours. There’s a movement away from the big, massive, machinery of Arthur and George or the pyrotechnics of your earlier books.

JB: I think it’s a question of age and liking compactness.

JF: It’s incredible. This book and Layers of Life, I think what we also experience in them is time, how time feels.

JB: Hmm. I think that’s another thing. As you get older, you understand time, you understand fictional time better, how to move in time, how to move through time in fiction. For example, in “Sense of an Ending,” you get to the end of part where he’s 21, or 22, and then 40 years go by in a paragraph. I wouldn’t have done that when I was young. It is just something that you get better at. I think that the great person who moves through time without you really noticing what she’s doing is Alice Munro. Extraordinary. You have a 25 page story and all of a sudden you’ve got the person’s complete life. How did she do that? You aren’t noticing and then suddenly you’ve got the whole life. And Updike, in his later work, he got very good, and canny and clever about time. So we do learn some new tricks.

Photos by John Freeman.