How the Prospect of Publishing Can Paralyze the Writing Process

Sofia Samatar on Balancing Self-Compartmentalization With the Joy of Creation

The dream is to create a book that will also be a tonic: not a course of study but a course of treatment. “I’m beginning a new book to have a companion,” wrote Hervé Guibert, “someone with whom I can talk, eat, sleep, at whose side I can dream and have nightmares, the only friend whose company I can bear at present.” He had been reading The Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon in the country. Shivering with cold, he bit into an overly salty biscuit.

I copied his words and sent them to you by email, including his parentheses: “(Living with a book, even when one isn’t writing it, is altogether marvelous.)” That’s what we were looking for, the altogether marvelous. I wrote to you of a writing method: Take notes on index cards and put them in a shoebox. When the box is full, the book is done. This method seemed to me comforting. We were searching for a writing method that was less like writing and more like living. I really want to write my next book that way, I wrote to you, as notes that can take in everything: a Compleat or commonplace book, a companion text. It would be a handbook, I wrote. The book you keep ready to hand. A circadian practice, a gentle dependency. You’d live with this dream text as with some necessary daily drug. You’d sit up with it—or it would sit up with you—as one sits up with the dying.

“This is what is diabolical about prose, it is never finished,” said Flaubert, cooling his cheeks with the palms of his hands, then cooling his hands against the iron knobs of the tall andirons. But we weren’t afraid of the diabolical; on the contrary, we desired it. I, for instance, was inspired by Aimé Césaire, who published at least three versions of his Notebook of a Return to the Native Land between 1939 and 1947. Perpetual magic: a never-ending book. A sustained delirium of rotting straw, obsessive bells, and rain. You, too, you wrote, were entranced by impossible projects, by books that are never written and books that never end. You wrote to me of the nineteenth-century tradition of the deathbed memoir, a book dictated from one’s final pillow. It was utopian, diabolical, ideal.

Once, I wrote to you, the internet seemed to promise me an interminable scroll. And there were the social connections, too, branching across space. But then I became disgusted with my name. Now I feel more intensely than ever the desire for an endless text. It’s the only solution to the problem of literature. Only when a book ends and is published does it enter the realm of the name. If you never finished a text, you’d never wind up there, in what I called, perhaps with a hint of hysteria, the blood-soaked arena of the publishing world. The best book, I wrote, would be the one that lasts your whole life. At some point, you would simply leave it behind.

I realized that there was a tyranny of identity experienced by all authors, and a second tyranny reserved for those with representational bodies.

I think we had been almost stunned by publishing. It sent us into retreat. But we tried to be generous with our younger selves, the ones who thought it impossible that they would ever be published, for whom publication was the one thing, the consuming desire. Back then, I confessed, when no one was paying attention to my writing, I habitually drew attention to my person. In retrospect this seemed to me low, shameful. I am trying to say, I wrote to you, that I am not above any of this. I still felt embroiled in it: the name, the skin, the color, the gender expression, the cultural practice I called the diversity sideshow, the question of whether confession was a source of radical power or a trap that sewed one up in one’s own carcass, the question of whether it was in fact shameful to draw attention to one’s race and gender in literary discussions or whether what was really shameful was leaving these things out, and the possibility that the idea of literature as a privileged spiritual ground was romantic, reactionary, dangerous, and dumb.

Your friend wanted to plan a book party for you; you said you wanted a book burial instead. Bury the book. Throw it away. Publicity agonizes. You wrote to me of Goethe abandoning the court and running away to Italy, shifting his existence and his writing out of people’s sight, traveling under a false name to escape the author of Werther. There he would learn to draw, he would learn at last to write again, to hear the half-obliterated groaning of the spirits. Rilke hid behind his poems, then tried to hide his poems behind his hair, his hands, or any opaque object. He dimmed the passages with his breath. He made himself small, he hid as children hide, he raised a brief and happy cry. “Only an angel,” he wrote to himself and to us, “should have been allowed to look for you. But if then you cautiously glanced up, there was no doubt that they had seen you all the time, everybody in that hateful, hollow, peering hall: you, you, you, and nothing but you.”

I realized that there was a tyranny of identity experienced by all authors, and a second tyranny reserved for those with representational bodies. The exemplars. Exemplary: serving as a desirable model; characteristic of its kind; serving as a warning or deterrent.

To be asked to speak or write as a representation of a category causes woe. It was like being in mourning for something. I wondered what I was mourning, what I lacked moving through the fluorescent conference light with my name tag, my paper cup. I realized it was writing.

__________________________________

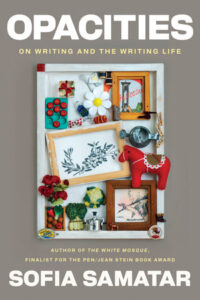

Excerpted from Opacities: On Writing and the Writing Life by Sofia Samatar. Copyright © 2024. Reprinted by permission of Soft Skull Press.

Sofia Samatar

Sofia Samatar is a writer of fiction and nonfiction, including the memoir The White Mosque, a PEN/Jean Stein Award Finalist. Her works range from the World Fantasy Award-winning novel A Stranger in Olondria to Tone, a study of literary tone with Kate Zambreno. Samatar lives in Virginia and teaches African literature, Arabic literature, and speculative fiction at James Madison University.