How the Killing of George Floyd Reflects America's Repeated History of Racism and Police Brutality

Curtis Bunn on the Black Lives Matter Movement, the Watts Riots, and the City as Powder Keg

A city was deconstructed in the wake of George Floyd’s killing. Minneapolis had a reputation as a progressive place that championed inclusivity and mobility, with a downtown replete with high-end shopping and fine culinary options.

Outside of the Chamber of Commerce’s depiction, Minneapolis also had a reputation for tension between its police force and its Black male population—and for sound reasons. Black men and women were appalled when, in 2015, Jamar Clark, 24, was shot during a scuffle with two white Minneapolis police officers. In July 2016, cops shot Philando Castile in his car while his girlfriend recorded the tragedy in St. Paul, the state capital and neighboring Twin City. Police also shot to death Mario Philip Benjamin, 32, when responding to a domestic incident in 2019.

In each case, the shooters were either not arrested or found not guilty.

In between those occasions, in 2017, a Black police officer named Mohamed Noor, born in Somalia, shot and killed a white woman in a dark alley, something Noor called “a mistake.” He was the only Minnesota officer to be convicted in an on-duty shooting in recent history.

And then George Floyd happened, and the powder keg the city had become exploded.

Andrea Jenkins, the Minneapolis city council vice president who represents the neighborhood where Floyd was killed, lives a five-minute walk from Cup Foods at 38th and Chicago, the site of the tragedy.

Jenkins said she shopped at Cup Foods for decades.

“I’ve been there hundreds of times.”

The Memorial Day 2020 when Floyd was killed, Jenkins said she was at home, watching Netflix, a show called The Politician. She did not learn of the tragedy until she received a call late that evening from a colleague and then the mayor of Minneapolis, asking if she had seen the video.

She hadn’t. It took her 45 minutes to find it on Facebook. It was 1 am.

“It was sickening,” Jenkins said of the video that shows Chauvin resting his knee and the force of his weight on Floyd’s neck for nine minutes, 29 seconds as Floyd begged for relief. “Absolutely sickening.”

And then she thought: “Here we go. Here we go again. The overall disregard for human life, disregard for Black life. I didn’t really start thinking about the social unrest that would eventually ensue or any of that. It was just a real emotional response [and] feeling.”

That same feeling permeated the Watts section of Los Angeles in August 1965, when a white California Highway Patrol officer stopped a Black man named Marquette Frye in his vehicle on suspicion of driving while intoxicated. A roadside argument broke out, which then escalated into a fight with police. In the commotion, witnesses said the police injured a pregnant woman.

Frye’s encounter was the accelerant on the fire—the culmination of consistent mistreatment by white officers—that sent Black residents into a fervor. Six days of civil unrest followed, with Watts set ablaze in the most destructive uprising: 34 deaths and $40 million in property damage.

Fifty-five years later, it happened in Minneapolis. Jenkins was aware of the Watts riots, also called the Watts Uprising and Watts Rebellion, and was fearful the same could happen in her city. After all, the parallel was striking: Both cities had a history of violence against Black people by law enforcement. Both cities had citizens who were fed up with the disregard. Both cities were one incident from an explosion. And America itself was rife with police brutality cases.

The difference that made all the difference: In Minneapolis, Floyd’s death was captured on video—all nine minutes, 29 seconds. There was no hiding behind the shield, no tainted, one-sided reports from enabling police officers. The world saw George Floyd murdered.

The world heard him beg for his life. It saw a cop, Chauvin, show no concern that the man could not breathe. It saw three other officers hold him down—and none of them come to the aid of a man who had been accused of passing a counterfeit $20 bill.

And so, the next day in Minneapolis, there was a rally as the nation and eventually the world shrieked in horror while viewing the video. The anger was palpable, the pain intense. But because so many Black men had died at the hands of law enforcement, few Black people were surprised. They had been desensitized to the violence. But that did not lessen the anguish or rage.

It saw a cop, Chauvin, show no concern that the man could not breathe.

The gathering in Floyd’s memory was peaceful, Jenkins said. “It was very peaceful. I mean, there was deep anger and frustration,” she said. “But it was being expressed, you would say, in traditional ways. You know, there were speakers.

“There were people from all over the city, people just kind of gathering, and supporting each other, calling for justice. Then that scene moved to begin marching down eastward on 38th Street towards the third precinct, which was about two and a half miles from 38th and Chicago.

“Things started around five in the evening. We cried and all of those kinds of things. I spoke. Many ministers and community activists and [the] community took off towards the precinct, maybe about seven-thirtyish, to march that two and a half miles to the police station.

“I did not go that far; I have multiple sclerosis, so walking that distance in a large crowd was not healthy for me.

“When I learned that it became this confrontation, I was surprised. There have been many reports about it, that the police maybe overreacted… I did not anticipate it.”

“Actually, there was nothing to be surprised about,” said Greg Agnew, a Minneapolis native who has had encounters with white officers. “You have a situation where a man gets killed as George Floyd did in a city with a terrible history of police not only killing Black men, but constantly harassing us. Yes, there would be confrontations during the protests because the cops still act like cops and the Black people are tired of it.”

Jenkins said she called the police chief and “begged” him to not use tear gas on the demonstrators. The fact that she knew that type of aggressive tactic would be employed speaks to the history of the city and America.

But the inspector on duty, who had the authority, called for tear gas, rubber bullets, and riot gear, elements that sent a clear and alarming message: They were prepared for war with the protesters, even if the protesters were only there to make a statement.

Those actions set the scene for the next night of protests, nights and actions that would define Minneapolis in this moment. Chaos erupted. Fires. Looting. Destruction. Leaders of the protests, who implored peaceful protests, decried the disruptions and were often recorded stopping white marchers from painting “BLM” on buildings and inciting mayhem.

Jenkins said she stayed at her partner’s home and watched it all play out on television for four days.

“Minneapolis was spared the damage that could have come because the BLM movement isn’t about violence and destruction,” said Ray Richardson, a radio host who has lived in Minneapolis for more than 25 years. “We had a right to be fed up and pissed off—and not just because of George Floyd. There’s a history in this town that pushed us to the edge. But the organizers pushed an agenda that was not like the 1960s nonviolent marches, but still not to turn things into chaos. It takes away from the message.”

“It was very spontaneous,” Jenkins said. “I mean, there were clearly reports of white supremacists in the area definitely involved… like cutting a fire hose and destroying property and burning down banks and post offices.

“We were getting reports from neighbors that people were driving around in trucks with no license plates, starting fires behind people’s houses. Garages were on fire. Those are the kinds of reports that people were seeing.

“And they were suggesting that these were not typical protesters. Many white neighbors [were] reporting that they [saw] white supremacists. Some had Confederate flags, lots of guys with tattoos. These were actually being confirmed by the law enforcement agencies that I was communicating with. Even though they were stating that these guys weren’t there to harm anything.

“[But] they were reporting some of the same things that… happened in Kenosha [Wisconsin] later in the summer, that white supremacist militias were just in town to protect their stores and protect things. But it was downplayed quite a bit by state authorities. I guess they thought they weren’t a threat.

They were prepared for war with the protesters, even if the protesters were only there to make a statement.

“That’s the only thing I can assume… even though we do know that since then many people who have been affiliated with those groups [were] arrested.”

The harsh reality is that there will be another Minneapolis—many of them, if history continues to repeat itself. In 1967, two years after the Watts riots, a Black cabdriver in Newark, New Jersey, was stopped for a minor traffic violation and beaten badly by two white police officers.

The news of the Newark incident spread quickly, and a crowd formed at the police headquarters where the injured driver was held. Protesters, exhausted from police misconduct and more, expressed their discontent by hurling rocks at police station windows.

The next two days were turbulent. New Jersey governor Richard Hughes called in the National Guard. The violence escalated, with 26 people dead and many Black people injured in the streets.

Then, two weeks after the Newark unrest of 1967, police raided an after-hours club in Detroit, where a welcome-home party was being held for two Black Vietnam War veterans. Police busted up the celebration and arrested 82 African Americans who were in the club.

The arrests lit the bomb within the Black community that had been waiting to go off. After five days of the disorder, 33 Black people were dead, 7,000 people were arrested, and more than 1,000 buildings were burned. This incident is considered to be one of the inspirations for the creation of the Black Panther movement.

Police brutality was the spark in these moments, but the true causes were the boiling resentment behind racism in general and in particular unemployment, poverty, segregation, inferior education, and other systemic issues of oppression.

Three months before the Detroit and Newark uprisings of 1967, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. foreshadowed what was to come in a speech he delivered at Stanford University called “The Other America.”

In it, Dr. King said: “All of our cities are potentially powder kegs… But in the final analysis, a riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it that America has failed to hear? It has failed to hear that the plight of the Negro poor has worsened over the last few years. It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. And it has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo than about justice, equality, and humanity… And as long as America postpones justice, we stand in the position of having these recurrences of violence and riots over and over again.”

More than five decades later, Dr. King’s words continue to ring true in America.

__________________________________

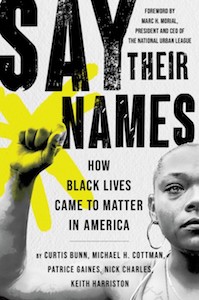

Excerpted from the book SAY THEIR NAMES: HOW BLACK LIVES CAME TO MATTER IN AMERICA by Curtis Bunn, Michael Cottman, Nick Charles, Patrice Gaines, and Keith Harriston. Copyright 2021 © by Curtis Bunn, Michael Cottman, Nick Charles, Patrice Gaines, and Keith Harriston. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Curtis Bunn

Curtis Bunn is an award-winning journalist at NBC News BLK who has written about race and sports and social and political issues for more than 30 years in Washington, D.C., New York, and Atlanta. Additionally, he is a best-selling author of ten novels that center on Black life in America.