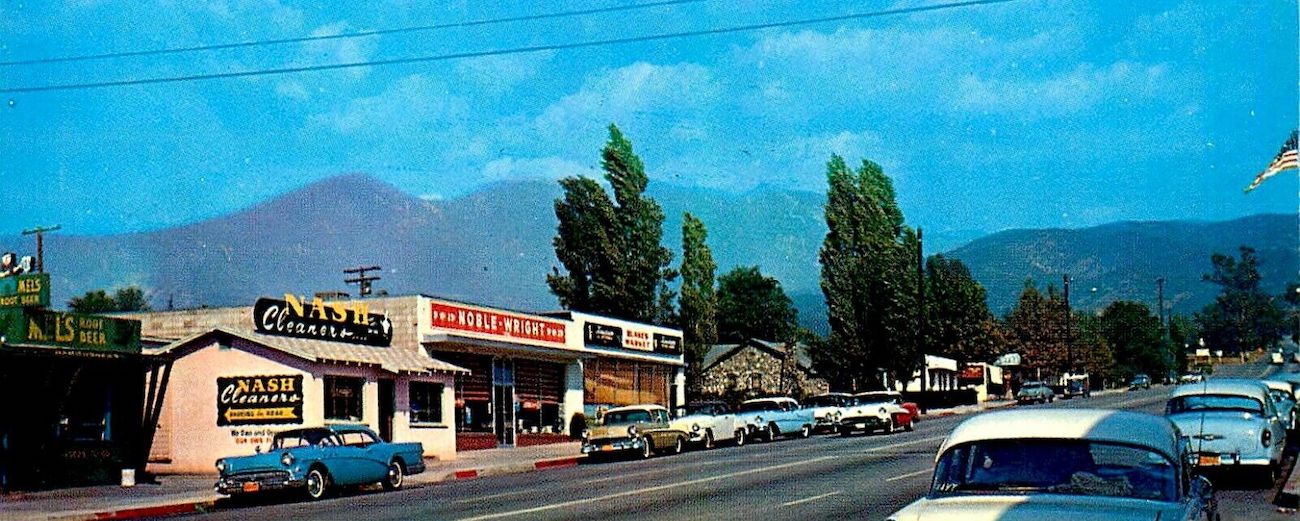

When I moved to California in 1996, I was following a horse. The horse’s name was Terson (I called him Mr. T). I bought him from a stable in Wisconsin in 1993, and kept him in a barn outside Ames, Iowa, where I taught at Iowa State. But I was tired of nearly freezing to death when I rode him in the winter, and, by the way, my husband, Steve, who had grown up in Iowa, had spent some time in Santa Barbara and wanted to move back. Eventually, Steve and Mr. T. agreed on Carmel Valley, California.

I could have said I was the native Californian, because I was born in LA, and my parents lived near Hollywood Park until I was about a year old, then moved back to the Midwest. Steve was born in Iowa, Mr. T in Germany. But no matter—like all migrants to California, we looked around and fell in love instantly with the new landscape and the everchanging but (almost) always pleasant weather.

At the time, I was known for A Thousand Acres and Moo, one of them openly set in Iowa and the other one sort of set in Iowa, at a land grant university. The first thing I did (inspired by Mr. T) was decide that of course I could breed racehorses, and I did, though none of them were successful. But Mr. T and the horses I bred gave birth to Horse Heaven, and in order to understand racing and breeding, I took a wonderful tour of California—Del Mar, Santa Anita, Hollywood Park, Golden Gate Fields, Temecula, Coalinga, and Davis, with many stops in between (San Francisco, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, San Diego).

The first thing I learned about California was how beautiful it is; the second thing I learned was that the climate and the scenery change every time you turn a corner or go over a mountain. I experienced this just the other day when I was walking in Monterey, and I left the Del Monte Shopping Center for Don Dahvee Park. I saw a path that I had never taken before, and it took me straight into the woods along a creek, natural, chaotic, and messy, not half a mile from the designer handbags at Macy’s.

*

Before I came to California, the only California writer I knew much about was John Steinbeck, from Salinas, who, judging by his works, was interested not only in the social world and the history of his native land but also in the landscape. In my favorite of his novels, East of Eden, he begins by describing the diversity of the Salinas Valley—the lupines and the poppies, the trees and the Spanish moss, the changing nature of the soil, and the danger and beauty of the Salinas River. All of his works take on economic and political themes too (obviously in The Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men), but one of the things you can’t help doing if you are a writer based in California is attempting to convey what it feels like to be here, moment by moment.

Every novelist’s life has taken place during times of turmoil, and many novelists choose to explore that turmoil.My family had one small connection to California—one of my grandfather’s many older sisters ended up in Vallejo, married to an astronomer who was a true crackpot, and who was also from central Missouri. His name was Thomas Jefferson Jackson See, and he earned his stripes as a crackpot by ruthlessly opposing Einstein’s theory of relativity until the day he died, convinced that the universe was made of ether. He worked for the US Navy, and was sent to Mare Island to use astronomy to tell the exact time of day and to let the captains of the ships know so that they could embark on their missions in the proper way.

And so I went to Vallejo and Mare Island to look around, gathering the information I needed to write Private Life (published in 2010). I also discovered a blot on US, and California, history that I hadn’t known about: the internment of the Japanese during World War II. (If you grew up in St. Louis, or elsewhere in Missouri, slavery and abolition and segregation were frequent topics of conversation.) What I learned about my great-aunt taught me more about the complicated history of California and more about the complicated history of my family.

*

When I began teaching creative writing at UC Riverside in 2015, I was pleased that my students were much more diverse than they had been in Iowa, and they all had stories to tell that were enlightening and dramatic. A term was ten weeks long, so every student had to produce a draft a week—three drafts each for the first three stories—and then to choose the story that most interested them and write a fourth draft of that one. Discussions of each draft lasted about twelve to fifteen minutes, and the students discussing each draft could not use words of judgment or praise—if they didn’t like something, they had to ask a question, such as “Why does Mary disappear after the first three pages?” The result was that the students got more intrigued by the stories they were writing, and as they fixed things, the stories grew more complex and unique.

Often, what the students who were reading the stories did not understand had to do with the connection between where the story was set and how this affected the main character and his or her friends and family. This meant that over time my students became more aware of the ecosystems and communities that they grew up in, and also more eager to depict them. Reading these stories worked for me, too, since there are so many enclaves in California that most of them are under the radar.

Two examples of stories that my students were working on were one written by a female grad student about an insane asylum from the early twentieth century that was run by her ancestors, which explores the cruelty of the system, in part from the point of view of one of the women who works at the asylum; the other was by an male undergrad student, about a family escaping from Mexico after the father is killed by gang members—some members of the family have transportation, but some of them have to walk the whole way.

The books I assigned were meant to be an exploration for my students, but turned out to be an exploration for me, too. I was quite familiar with Sue Grafton and had been enjoying her mysteries since the late 1980s—in some sense she replaced my youthful obsession with Agatha Christie, and both my students and I enjoyed the way Grafton created suspense, but also how she portrayed the idiosyncratic locations in and around Santa Barbara.

I was also familiar with The Woman Warrior, and I wanted my students to learn from the complexity of how the narrative mixes personal experience with traditional stories. We did not exactly read it as nonfiction, because the elements seemed imaginative to us and therefore worth learning from, for both fiction writers and nonfiction writers. In some sense, these books served my students as historical novels, about events and places that existed before they were born and that have now changed—I had felt the same pleasure in books I had read in school, such as David Copperfield and Giants in the Earth.

One book that my students and I found astonishingly compelling and informative was Kindred, by Octavia Butler, a novel that immerses modern readers in the experience of being enslaved in the mid-nineteenth century, and how that contrasts with the life the protagonist is leading in the present day. We understood that Butler was using science fiction to explore important issues that many of my students were familiar with but hadn’t been asked to imagine in such detail before. Little Scarlet, by Walter Mosley, offered similar insights and feelings. Some of my students were from the LA area, and Mosley’s dramatic depiction of the Watts riots and the racial issues surrounding them, plus the way he incorporated them into a thriller, was very alluring.

The more recent novels that we discussed showed them what they could aim for. I had spent a lot of time on an Ojibwa reservation in northern Wisconsin, but what Tommy Orange showed me and my students about the experiences of Native Americans in Oakland was completely new. The way that There There jumps around between the points of view of different characters (using first person, second person, and third person) also sparked discussions of the benefits that each point of view offers the reader and the author. I think that Orange, as the youngest of the authors, also provided my students a pathway to a fresh literary voice.

I did not make them read The Greenlanders, but they had a similar experience when I assigned The Good Men, by Charmaine Craig, which was about religious conflicts in France in the fourteenth century, was a little shorter, and was written in a more accessible style than my novel. Many of my students were fascinated by events they had experienced or heard about, and The Good Men offered a way to talk about how to imagine those events in detail and put them on the page, even if, when you start, you have very little idea of how to understand them.

The novel is, and always has been, a self-made form.The book I assigned that I think my students and I appreciated the most was The Sellout, by Paul Beatty. I taught it in my comic novel class, and it was the perfect example of using a comic and satiric voice to lure the reader into seeing the absurdity of the world that the narrator is living in. It was a major prizewinner, but easy for my students, and for me, to relate to. It fit perfectly into the desire that I had for my students to feel the presence of the writers around them, busily working and depicting the places in California that my students knew and wanted to write about themselves.

*

What is my justification for collecting the essays in my new book, The Questions That Matter Most: Reading, Writing, and the Exercise of Freedom? For me, it is that every novelist’s life has taken place during times of turmoil, and many novelists choose to explore that turmoil (for example, Émile Zola). In this way, being a novelist becomes a form of education. Let’s say that first comes fear, then comes rage, then comes curiosity, then comes a more complex curiosity as our imaginations encompass our characters and their feelings.

There was recently a short essay in the Guardian about how historical novels shouldn’t exist. It was written by a man who had just published a historical novel, and I think he meant it as something of a spoof, but if I had been arguing the issue with him, I would have said that all novels are historical novels, because those that outlive their authors teach future readers what life was like from the authors’ point of view at the time when the authors were writing them. A good example is Sir Walter Scott, one of the first novelists to explore eras several hundred years in the past (Ivanhoe, Quentin Durward).

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Scott did not have the archeological evidence we have, or other aspects of research that historians now employ, but he had the stories, passed down over generations, and he reimagined them and set them down in a new form—the novel, the historical novel. His work was hugely popular. The books are still readable and dramatic. My favorite of his are the novels he wrote about the religious conflicts of the seventeenth century, especially The Tale of Old Mortality. Is it accurate? As I was reading it, I was both enthralled and motivated to look up the history of those times and compare what historians had to say with what Scott wrote. And that is one thing historical novels do—they pull you in and make you wonder, not only about what really happened but also about how and why the author portrayed the events as he did.

Because of this, I think that I often forgive and even thank authors of novels for truthfully representing the era they lived in. Yes, Anthony Trollope shows signs of antisemitism, and I don’t like that, but it shows me who he is—he can’t help but reveal it. It is also true of Trollope that he was more interested in, and more insightful about, the lives of his female characters than any nineteenth-century male writer that I can think of. Was that because his wife read his work, day by day, and gave him advice? I suspect it is. Novels and novelists are complex, and that is why I prefer writing about complex issues in novels rather than in nonfiction.

The novel is, and always has been, a self-made form. We read them as children, go on reading them, and then decide to try writing one, to see how our own experiences look on the page. Not all of my students will have enough luck (or maybe dedication) to write about their experiences and stories, and not all of them will find a publisher or an audience, but I hope that the ones who are really dedicated do so, because their depictions of one of the largest, most beautiful, most populous, most diverse, and most contradictory states in the US are revealing and fascinating.

Most of the essays in this book have been assignments—I am handed a topic and asked to reveal my thoughts. I hope that I have used them in the same way that I have used my novels—to learn more about something that I thought I understood, and to understand that topic, or issue, with more clarity and nuance.

__________________________

Excerpted from The Questions That Matter Most: Reading, Writing, and the Exercise of Freedom by Jane Smiley. Copyright © 2023. Available from Heyday Books.

__________________________

Jane Smiley will be in conversation with David Ulin hosted by Writer’s Bloc at the Wallis Theater in Los Angeles on June 15.