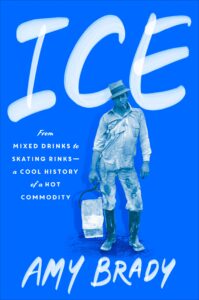

According to a 2020 poll by Bosch, a full 51 percent of Americans self-identify as “obsessed” with ice. As I write in my new book Ice: From Mixed Drinks to Skating Rinks—a Cool History of a Hot Commodity, the American ice trade was by the mid nineteenth century the largest of its kind in the world. Nowhere else on earth were people consuming as much ice as people were in the United States.

Writers from abroad were astounded by the sheer amount of ice that could be found in the country. When Charles Dickens visited the young republic in 1842, he gawked at the American “icehouses [filled] to the very throat” and “the mounds of ices” that Americans ate in hot weather. (Interestingly, ice doesn’t appear much in the English novelist’s work, either as an element or as metaphor.

Perhaps that’s because, after this first visit, he wrote American Notes for General Circulation and the spent twenty years wanting nothing to do with Americans—not because of their obsession with ice, but because of what he saw as their obsession with money.)

The French writer Jules Verne was famously intrigued by American culture, and it seems he was particularly taken by the country’s ice. He visited America only once, but Americans and the North American continent make appearances throughout his writing, including The Adventures of Captain Hatteras, an 1864 novel in two parts. It tells the story of Captain John Hatteras, who is convinced that the North Pole is free of ice and therefore passable by ship (it wasn’t passable in Verne’s day, but just as the writer predicted the invention of the helicopter, the jukebox, and the electric submarine, he also unfortunately prognosticated an ice-free Arctic). On their way, the captain and crew dock at “the island of New America,” where the men build a “snow house” to stay the winter—an abode likely inspired by North American indigenous building techniques and the many ice houses Verne saw on his visit.

Verne further establishes the wondrous capacity of ice by having one of the crew, a Doctor Clawbonny, start a fire by crafting an “ice lens” that refracts and focuses the rays of the sun.

But it was in the writing the renowned American authors of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that suggest the country has been in the grip of this obsession for some time.

Consider, for example, twenty-eight-year-old Henry David Thoreau, who waxed rhapsodic about ice in Walden: “The first ice is especially interesting and perfect, being hard, dark, and transparent,” he wrote. And later: “Ice is an interesting subject for contemplation. Why is it that a bucket of water soon becomes putrid, but frozen remains sweet forever?”

Thoreau loved ice, but he wasn’t always fond of the men who harvested it. On one unusually cold night during the winter of 1846, the writer stood outside his log cabin and glowered at the cadre of ice-harvesters full of “jest and sport,” who were chiseling at and hauling away frozen chunks of Walden Pond. He had come here to escape the bustling life of Concord, and the noise was interrupting his respite. Thoreau approached the ice-cutters, but the men didn’t stop working. Instead, they joked that he might like to help them cut the ice in a “pitsaw fashion,” which, in the parlance of the day, meant that he would be standing underwater and freezing to death. Burn.

By the end of the nineteenth century, frozen water had become on par with coal in terms of importance.The Walden ice men weren’t just witty; they were strong and brave and able to crack frozen lakes into hundreds of blocks of ice for profit. Their boss was the man who launched the American ice trade, a wealthy Bostonian named Frederic “the Ice King” Tudor. In 1806, Tudor may or may not have been the first person to land on the idea to sell ice from New England lakes and rivers to people in warm climates around the world—but he was definitely the first person to figure out how to do it.

By the 1820s, the cubes that clinked in glasses of iced tea in Charleston, the ice that cooled hospitalized patients in Savannah; the ice that formed ice cream in the White House during the hottest months of summer—all of it from New England. Ice was so unusual (and expensive) in the South that locals called it “white gold.”

Ice continued to obsess America. By the end of the nineteenth century, frozen water had become on par with coal in terms of importance. In an 1895 essay entitled “What Paul Bourget Thinks of Us” published in the North American Review (a journal founded, by the way, by Frederic “the Ice King” Tudor’s older brother William), Mark Twain muses on what sets the United States apart from other nations. He considers a range of temperaments and morals, but ultimately decides that “the national devotion to ice-water” is the country’s most distinctive trait.

“When [Americans] have been a month in Europe we lose our craving for [ice],” he continues, “and we finally tell the hotel folk that they needn’t provide it any more. Yet we hardly touch our native shore again, winter or summer, before we are eager for it. The reasons for this state of things have not been psychologized yet.”

Here Twain’s characteristic wit reads like a gibe, but he found ice just as wondrous as Thoreau and Verne did—albeit ice from a different source. By the 1890s, the American innovative spirit that gave the world the cotton gin and the telephone, also produced the world’s first ice plants, large factories that could yield thousands of blocks of ice per day—barely enough to keep up with the people’s growing desire for cold.

This new technology rendered the natural ice-cutting industry all but obsolete, because ice from plants contained fewer impurities than natural ice and was therefore much clearer, cleaner, and healthier to consume. Ice plants froze toys and fruits inside their ice blocks to demonstrate such clarity, a marketing ploy that caught Twain’s attention. On a visit to such a plant in New Orleans, the writer stood in front of a block and marveled at how the frozen objects “could be seen as through plate glass.”

It wasn’t just the ice industry that inspired writers, however. Ice as it was found in nature wielded its own kind of rousing power, as did the fortitude of the brave people who attempted to navigate it, whether by choice or not. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) contains one of the most remarked upon ice-related conceits in American literature. It follows Eliza Harris, an enslaved woman seeking freedom (who was based on a real woman) as she crossed the Ohio River with her infant in her arms. Stowe’s description of Eliza’s leap through the perilous, icy water is, well, chilling:

It was now early spring, and the river was swollen and turbulent; great cakes of floating ice were swinging heavily to and fro in the turbid waters. Owing to the peculiar form of the shore on the Kentucky side, the land bending far out into the water, the ice had been lodged and detained in great quantities, and the narrow channel which swept round the bend was full of ice, piled one cake over another, thus forming a temporary barrier to the descending ice, which lodged, and formed a great, undulating raft, filling up the whole river, and extending almost to the Kentucky shore.

The ice, which touches the shores of Kentucky and Ohio, serves as a metaphoric reminder that the North wasn’t so different from the South, in at least one, significant legal sense. Though Ohio was a free state, the Fugitive Slave Act required all citizens—even those in the north—to help return the enslaved to their masters. Even after risking her life and the life of her babe, Eliza still wasn’t safe from capture. This passage, among so many in the novel, lends the novel its explosive, persuasive power.

Ice serves as a very different kind of metaphor in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1920 short story “The Ice Palace.” It’s set in a palace constructed entirely of ice based on the one built in St. Paul, Minnesota in 1887 (which I also write about in my book.) The story stars Sally Carrol Happer, a young woman from Georgia, who’s engaged to Harry Bellamy, a young man from an unnamed “Northern city.”

After complaining about her always-warm, never-changing Georgian environment, Harry takes her to a winter carnival, where they enter a palace made entirely of ice. Happer is not fond of the cold and begins to worry that she might be stuck for the rest of her life with a man who seems to treasure it.

Suddenly, the lights in the palace go out, and Sally gets separated from Harry. Fear overtakes her. She feels a “deep terror far greater than any fear of being lost.” In this palace surrounded by ice, she feels forced, if a bit melodramatically, to contemplate the “dreary loneliness that rose from ice-bound whalers in the Arctic seas, from smokeless, trackless wastes where were strewn the whitened bones of adventure. It was an icy breath of death; it was rolling down low across the land to clutch at her.” Sally was eventually found, but the couple’s engagement didn’t last.

Ice is everywhere in American literature. When we expand our notion of “America” to “the Americas,” we can include the most famous literary sentence ever to mention ice, that strange, startling line that begins Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.”

It’s the kind of first line that burrows deep in the brain. Its structure is so unusual, so surprising, it moved at least one critic to consider a new way of looking at time. In some ways, the line is perhaps as miraculous to readers today as the sight of ice was to Colonel Buendía. In the small South American town of Macondo in an age before electric refrigeration, what would look more magical than sparkling cold ice?

As Helen Rosner once wrote in The New Yorker, “outside of frigid climes, ice is always a miracle.” It might also be America’s most literary element.

_______________________

Amy Brady’s Ice: From Mixed Drinks to Skating Rinks–a Cool History of a Hot Commodity is available now from Putnam.