How the Associated Press Erased the Voice of a Climate Justice Activist—and an Entire Continent

Vanessa Nakate on Arctic Basecamp, Davos, and Getting Cropped Out of a Major News Photo

Early in January 2020, Arctic Basecamp, an organization of scientists raising the alarm about the rapid warming of the Arctic, invited me to Davos. I was intrigued. I would join five other young activists and sleep in a chilly expedition tent outside the venue to show attendees at the World Economic Forum that they, like us, had to move beyond their comfort zone if we were to address the climate crisis.

At that point, I’d never heard of Arctic Basecamp or Davos or, for that matter, the World Economic Forum (WEF). When I told a friend who’s also now an activist that I’d accepted the invitation, she said she’d researched the event and that many rich people would be attending. That didn’t interest me as much as the prospect of seeing snow for the first time. I knew that Switzerland was a mountainous country, and since it was January in the northern hemisphere, I assumed it would be cold. Arctic Basecamp’s team told me they’d be supplying the winter gear I’d require, so I needn’t worry.

I once again borrowed my father’s suitcase, which was heavy and had wheels, and packed it with all the layers I thought I could wear. Then I set off for Entebbe Airport, flew to Zurich, and got my first glimpse of the Alps. I took a train to the ski resort of Davos and arrived around midnight.

When I stepped out of the heated carriage, the cold hit me like a sledgehammer. In my effort to make sure I caught the correct train in Zurich, I’d forgotten to remove my gloves from my suitcase and I was wearing just a sweater and scarf over my shirt. I could see only a few streetlights, and I grew nervous. For a woman in Uganda to be outside alone at this late hour and on a badly lit street would be considered reckless. Plus, I had no idea where to find the funicular railway to take me up the mountain to where the Arctic Basecamp tents were set up. Thankfully, I came across an old man who noticed how lost I looked and he asked some teenage boys to help me drag my suitcase to the funicular station.

By this time, my hands were aching from the cold, and everything I touched hurt. My body was shaking to keep warm, and I’d begun reciting prayers in my head. What I hadn’t grasped was that the funicular departed only every half-hour at that time of night, so I could have been in for a long wait. Although I was relieved that it was well lit, it was only marginally warmer than outside. I couldn’t summon the energy to open my suitcase to pull out more clothes. I was staring at my feet in despair, thinking I’d die of hypothermia, when a group of men entered and sat nearby. One of them, Callum Grieve, a climate change consultant who has since become a good friend, kept looking at me. Eventually he asked, “Are you going up to Arctic Basecamp?” When I nodded miserably that I was, Callum replied, “You must be Vanessa. We were searching for you, and we couldn’t find you. We’re so pleased you’re here.”

Callum lent me his coat and, after the funicular finally made its way up the mountain, he helped me carry my suitcase. He’d decided that I really needed to thaw out rather than spend a night in a tent in subzero temperatures. Some of the staffers from Arctic Basecamp gave me warm clothes and sat me by the fire in the hotel lobby. Finally, I was shown to my room, where I was advised to have a warm bath, drink some tea, and go to bed with a hot water bottle. I have never looked forward to bed like I did that night.

When I woke up in the morning, my hands no longer hurt, and all eight fingers and two thumbs were still attached. And the view of the Alps was spectacular.

That day was full of media interviews and spending time with the other activists also invited to join Arctic Basecamp: Wenying Zhu, who’d led the Environment Protection Volunteer Team at her university in Shanghai, China; Kaime Silvestre, a law student from Brazil, who was campaigning on behalf of the Amazon rainforest; Sascha Blidorf, who’d coordinated FFF (Fridays For Future) protests in Greenland and had run for a seat in the Danish Parliament; Brix Whiteman from England, who was volunteering at Arctic Basecamp with his brother; and Eva Jones from the US, who advocated for homeless women. I’d met Kaime before, at the UN Youth Summit in New York. Unlike me, he’d really come prepared for the cold.

Together we traveled down to the village of Davos, where the scientists from Arctic Basecamp spoke about how climate change was transforming the Arctic. Over the last three decades, the Arctic has warmed at a rate twice as fast as the rest of the planet, leading some to predict that the Arctic will be ice-free by 2035. Although our group was in Davos, we weren’t attending the World Economic Forum itself (we hadn’t been invited). Instead, we engaged in “outside” advocacy and awareness-raising. We visited a local school, where we met some of the students, who ranged in age from ten to 15. I was impressed. The kids were curious about my activism in Uganda and were eager to learn how they, too, could become climate activists.

That Friday, January 24th, I was invited to speak at an FFF press conference with European climate activists Isabelle Axelsson and Greta Thunberg from Sweden, Loukina Tille from Switzerland, and Luisa Neubauer from Germany. We then participated in a climate march through the streets of the resort town, attended by hundreds of people who’d traveled to Davos to demand that WEF participants make the climate crisis their priority. Afterward, I joined some of the climate activists for lunch. That’s when I saw the photo from the Associated Press (also known as “the AP”) featuring Isabelle, Greta, Loukina, and Luisa… but not me. A photo had been taken of the five of us standing together. But when it was published by the AP, I—the only non-white activist—had been cropped out.

When it was published by the AP, I—the only non-white activist—had been cropped out.

In the hours after the photo, I had little time to process how I felt. I’d been running on adrenaline and was bone-tired. I posted a tweet from the dining area asking the AP why I’d been cut out of the photo. But I needed to return quickly to Arctic Basecamp because most of the activists, including me, were leaving Davos that night for our home countries. The conversation there was muted; everyone was busy packing.

From the Arctic Basecamp, I decided to record a video describing what I thought had happened. I was definitely emotional, and although I’d waited to do the live stream until I could compose myself, I couldn’t refrain from crying. “You erasing our voices won’t change anything,” I said. “You erasing our stories won’t change anything.” And then I added something very personal. “I don’t feel OK right now. The world is so cruel.” As I tweeted at the AP on Friday evening: “You didn’t just erase a photo. You erased a continent.”

So much was happening it was difficult to grasp it all. A few hours later, I was on a train back to the Zurich airport, and then on an overnight flight home. Wi-Fi wasn’t always available, and my phone battery was running down, so I couldn’t follow the response to my tweets and video in real time. It was clear from what I could access, though, that my being cropped out had struck a chord, and many people around the world shared my outrage. I could also see retweets and posts from other climate activists and friends from home sending me good wishes and encouragement. The journey back to Uganda, however, gave me a chance to think more, and to figure out why the photo-cropping evoked such a strong reaction in me. As my flight neared Entebbe Airport, the words that came to me to describe how I felt were heartbroken and depressed.

Even now, well over a year after being cropped out of that photograph, it’s hard for me to talk about what happened, and the hours and days that followed. I won’t deny I felt personally humiliated, as though I was invisible, and that I’d wasted my time in Davos. I admit that being left out of the photo played into my doubts about my worth as an activist and whether I brought anything of value to the fight for climate awareness and climate justice. And I was stretched thin: in Davos, I was far away from home and engaged in a constant struggle to stay warm. In addition, I’d spent the previous few months attempting to absorb a dizzying array of new experiences, while keeping up my commitments to Fridays For Future strikes.

I know some people have wondered why what happened was such a big deal. After all, the same day the photo was published, then-AP executive editor Sally Buzbee issued a statement, recognizing that I as “the only person of color in the photo” had been cropped out, which she termed an “error in judgment.” She then sent an apology via her personal Twitter account. The AP replaced the photo with another where I was visible, and shared more photos they’d taken at the press conference, in which I was seated in the middle of the five of us.

The AP’s director of photography insisted that cropping me out hadn’t been a deliberate act of erasure, but was done on “composition grounds” by a photographer under intense time pressure: I’d been cut because the building behind me was distracting. But, aside from the fact that the cropped photo still contained two other buildings, the question is, Distracting from what or whom? The Alps in the distance? My four white, European colleagues who were standing in front of the mountains? Or Greta herself?

The tears I’d shed in my Twitter video were not only ones of personal sadness, but of frustration and anger too. I was frustrated because the article accompanying the photo was titled “Thunberg Brushes off Mockery from US Finance Chief,” and the AP had not only removed my photo but removed me from the list of participants. It hadn’t included a single one of my comments from the press conference where the five of us had spoken. This was deeply ironic, since, at that press conference, in addition to urging the delegates to break out of our comfortable addiction to fossil fuels, I’d asked journalists to reach beyond the comforts of their normal reporting: “It is time to report stories from every part of the world,” I’d said, “because people are suffering from every corner of the world.” Greta, too, had urged the journalists there to direct questions not only to her but also to the rest of us.

I was also frustrated because the AP generates 2,000 stories a day and a million photos a year. It operates in 250 locations and reaches more than half the world’s population—particularly in places with limited access to world news. By cutting me out of the photo they’d originally sent to global media organizations, the AP had denied an African activist a chance to be seen and, possibly, her message acknowledged.

I was angry because there were photos from other agencies and news outlets in which I had been included. That made me feel that the decision by the AP to leave me out was no accident. It wasn’t the result of the photo being too large to download or the wrong size for newspapers. No, it was as if someone had determined I was the odd one out, an aberration, and that the photo wasn’t satisfactory if I remained in it. Five of us were standing in a row; but there were two “ends” of that row and only one was shortened.

As the outcry on social media grew and the story of the photo-cropping made its way to the mainstream media, the AP was asked to respond. While they did express regret, I remain skeptical. I never received a formal message of apology, just a tweet. I also knew that the AP had released the uncropped photos only after the uproar.

__________________________________

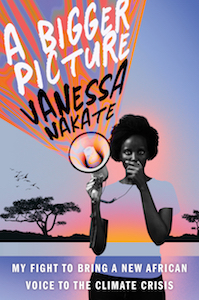

Excerpted from A Bigger Picture: My Fight to Bring a New African Voice to the Climate Crisis. Used with the permission of the publisher, Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2021 by Vanessa Nakate.

Vanessa Nakate

VANESSA NAKATE is founder of the Rise Up climate movement and the Vash Green Schools Project, which aims to install solar panels on all of Uganda's 24,000 schools. She has spearheaded the Save Congo Rainforest campaign. The United Nations named her a Young Leader for the Sustainable Development Goals in 2020, and Time magazine named her to its Time100 Next list in 2021.