How Stories Emerge from Afro-Diasporic Collective Memory

Destiny O. Birdsong on Language as a Currency of Knowledge

I grew up with a deep understanding that language—particularly African American Vernacular English—is the currency of knowledge, and I learned this by growing up in a family that was mostly quiet about deep and painful secrets. It wasn’t uncommon to walk into a room and overhear snatches of conversation about the great-grandmother whose children might not have all been fathered by her husband, the suspicious and unexplained death of a beautiful young aunt, or the teetotaling deaconess relative who carried on a decades-long affair with a married parishioner.

As a curious child, I questioned my mother and aunts about our family’s secrecy—inquiries that, on a good day, went ignored, and on a bad day, got me in trouble. Still, that never stopped me from wanting to know. More important, the ways adults used euphemisms, hyperbole, and even grunts and gestures fascinated me. There was an intimacy in those exchanges that I was too young to be a part of then, but it felt rich and binding; it seemed like the ways my family members talked to each other made them more knowledgeable and more powerful adults. It also drew them closer. Talking in their coded language seemed like the very thing that made them a family.

While “interiority” has long been the proclaimed the mark of “literary” fiction, it does not always reflect the realities of communities like mine, nor is it always a useful approach to Afro-Diasporic literary craft. I would also argue that it is not even the most effective method of characterization, or of illustrating a character’s evolution over the course of a narrative. This feels particularly true for the protagonists in my triptych novel Nobody’s Magic, who are often coming into a deeper understanding of themselves and the lives they want to live among people with whom they have rich, but complex and sometimes painful intimate relationships.

*

I am often wary of non-Black readers who seem obsessed with Black art but cannot tell me what makes it good. In a recent conversation about a piece of writing, I asked a group of mostly white readers what they liked about it. “It’s soulful. There’s a lot of feeling,” one cooed. “Yes, it’s very emotional,” chimed another. When I asked how it was emotional and pointed to a particular line as a possible point of entry, they could only repeat the line back to me as an answer. It simply was what it was. It needed no interrogation, and subsequently, no rigorous examination.

The mark of a good story is in the telling, but it is also in the talking; we come to a greater understanding of ourselves through collective and shared memory.

The truth is that, for some readers, it is easier to participate in voyeuristic consumption of non-white art when the character has no voice, no agency, and at times, no sense of community. I think of writers like Toni Cade Bambara, whose debut novel The Salt Eaters features extensive dialogical exchanges between living and ancestral characters, and while this is a book I often discuss with other writers of color, I’m hard pressed to think of a single white person I know who has read it, or who is even familiar with Bambara’s work outside her much-anthologized short story, “The Lesson.”

The Salt Eaters is a brilliant book, but perhaps too uncomfortable for some readers in its indictment of global racism, economic disenfranchisement, and misogynoir in some places, and its lack of concern for the white gaze in others, turning instead to rich conversations about histories and issues that lie exclusively within Black communities. In work like Bambara’s, characters spend less time talking at the reader, a trope that allows for cathartic moments of chastisement or opportunities for the reader to mine characters for what seems like firsthand knowledge of how it “feels” to be Black. Instead, these characters spend much more time talking to one another.

Anyone who has picked up my new novel, Nobody’s Magic, can tell you that I worked hard to do exactly that. Many of my characters, like those who populate Suzette Elkins’ triptych, thrive in conversation. More important, these exchanges are often psychologically evolutionary—much more so than moments of quiet reflection or interior monologue. Perhaps one of the most dynamic scenes occurs between Suzette and her love interest, Doni, as Doni explains Suzette’s father and his complete control over the auto shop where Doni is employed.

When Suzette begins putting together the pieces of an old crime, Doni responds to her by replying to his own unnarrated thoughts. “Naw. Naw, he wouldn’t do no shit like that,” he says, shaking his head, not daring to divulge what the “shit” might actually be. Yet, only a few seconds later, he equivocates, telling her: “Yo daddy…he really is that powerful.” Though Suzette quickly reminds him that her father is incapable of causing such harm, she too is unsure she believes what she is saying.

In this moment, both Doni and Suzette exchange vital information about the man who, up until that point, controls much of their fates. Each character is coming into knowledge about Mr. Elkins and developing a much deeper—and somewhat frightening—understanding of their own vulnerability, not to mention the consequences of continuing their budding relationship. Their reticence to even name Curtis Elkins’ potential crimes reinforces the deep respect they have for him in spite of his many suspected and committed acts of cruelty. It is at once defiant and communally respectful, something that a younger me often felt in the faces of the adults who refused to tell me the full story, even when I knew that their doing so would give me agency.

Another character, Agnes Kirkkendoll, was never one to be honest with anyone about how she felt, and even the third-person limited narrator of her triptych doesn’t have all the answers. This is a direct result of Agnes’s adolescent trauma, but also of the fact that she has not yet learned how to be open safely. Every attempt in her early life caused her pain, especially in her relationship with her sister, Berniece.

Interestingly, it is not until Agnes is forced to confront her past in some explosive conversations that she is finally able to see a way froward for herself, something that she has been unable to do in the two decades since she left home. She begins this journey when a stranger, Prime, begins chatting with her while she is working a job she hates in a city she has never lived in, and their conversations lead her from one drastic life decision to another until she finally has little choice but to face her greatest pain. Together, Agnes and Prime begin the unpredictable process of picking up the pieces of their lives and starting over, though neither is quite prepared for what that will entail.

*

If I learned nothing from the people who raised me, I learned that the mark of a good story is in the telling, but it is also in the talking; we come to a greater understanding of ourselves through collective and shared memory, dialogic exchanges, and interrogating each other’s choices even as we interrogate our own. Nobody’s Magic offers an exploration of the ways that can happen among Afro-Diasporic communities of all kinds, even among people with albinism, who are often thought of—and treated as—members on the outskirts of society. In literature and elsewhere, we are robbed of our own voices, our own accounts of our lives, and relegated to the novelty of our condition.

I worked hard to ensure that characters in Nobody’s Magic are at the centers of their own stories, imparting knowledge to the reader, but also requiring them to pay attention to both word and gesture in order to more fully understand the characters’ lived experiences. And the little girl I was—the one who always wanted to be in the know, to share, to both listen and tell—is proud.

__________________________________

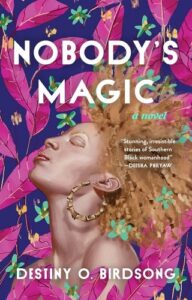

Nobody’s Magic by Destiny O. Birdsong is available via Grand Central Publishing.

Destiny O. Birdsong

Destiny O. Birdsong’s writing has appeared in The Paris Review, African American Review, and Catapult, among other publications. She has received the Academy of American Poets Prize and the Richard G. Peterson Poetry Prize. Her critically‑acclaimed debut collection of poems, Negotiations, was longlisted for the 2021 PEN/Voelcker Award and published by Tin House Books.