How Politically Radical Women in 19th-Century France Were Made Into Misogynistic Caricatures

Jill Richards on the Petroleuses of the Paris Commune

The women were ugly, to be sure, but not quite ugly enough, or not as ugly as one might have expected, a somewhat regretful Léonce Dupont recalled, in what would become a standard account of the fourth military tribunal of the Paris Commune, the first of the trials to be devoted to the female communards. Indeed, it seems that the five women produced by the court that day were quite a disappointment.

For Dupont, the accused were “not hideous enough, not old enough, not criminal enough to inspire horror.” This overt lack of monstrosity did not stop the author from further elaboration. Schooled in the finer arts of physiognomy, Dupont paid special attention to the accused’s facial deformities. Though he admitted it not very sporting to focus on the ugliness of women, Dupont allowed that Elizabeth Rétiffe had a large nose and “beast-like” grin. She perspired too much, having overdressed for the weather.

Léontine Suétens’s left cheek was scarred, as though someone had bitten her, most likely, Dupont suggests, in a brothel. The washerwoman Joséphine Marchais seemed dirty and withered, though still angry looking, “like a fury. More gentle was 24-year-old Eulalie Papavoine, unfortunately in possession of a large “ at face.” Perhaps running out of steam, Dupont found the last defendant, the laundress Lucie Marris Bocquin, merely “sweet,” though her mouth was too big.

The fourth military tribunal tried five women, all accused of arson during the final weeks of the Paris Commune. This social experiment in working-class radicalism, what Marx called the first proletarian revolution, rejected the authority of the French Third Republic and governed Paris from March 18th to May 28th, 1871.

It wasn’t until the last week in May, when the French army invaded the city, that the fires were set, burning down the Tuileries Palace, the Richelieu library of the Louvre, the Hotel de Ville, and dozens of smaller buildings near the Rue Royale and the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. In the months that followed, these fires were attributed to the female communards, named pétroleuses.

Key to understanding the legal aftermath of the Commune for its female participants is a problem of categorization, but not necessarily of what the women did. What takes center stage are the vengeful feelings that prompted such action and the ways these feelings might manifest in the body as a distortion of femininity that could be readily observed. Consider, for instance, the journalist for Le Figaro, René de PontJest, who was also disappointed with the looks of the accused. That said, Pont-Jest makes a cleaner distinction between what was expected and what was seen.

Cartoons show befouled ghouls carrying cans of petrol. There are mustachioed women and those rendered pig-like or insane.

The crowd had awaited the trial with some excitement, no doubt, Pont-Jest writes, because the very word “pétroleuse” summoned the most sinister menace, that is to say, “savage hordes of she-devils.” However, to the audience’s dismay, the persons led to the bench were “ruined girls, ragged, grown pale from their night watches or darkened by the sun, their voices hoarse, their eyes dull, no longer feminine or masculine, beings without sex, without morality, without conscience, without even cynicism.”

Though he does not use the language of ugliness or beasts, Pont-Jest makes it clear that the accused women could not really be women, or men, or, one might surmise, altogether human.

In many ways, both journalists were merely taking cues from what had been a summer of political caricatures. Well before the trials began, the pétroleuse had become a fixation in the popular press. Cartoons show befouled ghouls carrying cans of petrol. There are mustachioed women and those rendered pig-like or insane. Propaganda postcards render the pétroleuse as witches or harpies grimly watering the fires of destruction.

The conservative press invoked the language of she-wolves, hydra, and other monstrosities. In the months that followed, the prosecution took up that language of monstrosity in a slightly different key. What began as a somewhat unremarkable misogyny, likening radical women to fantastic beasts, became literalized through the quality of women’s legal personhood. As the persons before the law, the female communards offered a particularly visible animation of the paradox between abstract rights and materially unequal subjects.

The women were active within the public sphere of politics while formally excluded from universal political recognition, both within the Second Empire and the Commune’s Central Committee. They were political actors but not citizens. They were human, but not subject to the rights of man. In some extreme cases, the pétroleuses seemed not quite human at all, but something else more difficult to name, “no longer feminine or masculine, but beings without sex.”

__________________________________

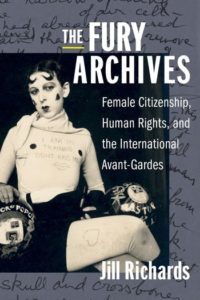

Excerpted from The Fury Archives: Female Citizenship, Human Rights, and the International Avant-Gardes(c) 2020 Jill Richards. Used by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Jill Richards

Jill Richards is assistant professor of English and affiliated faculty in the Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Program at Yale University. She is a co-author of The Ferrante Letters: An Experiment in Collective Criticism and author of The Fury Archives: Female Citizenship, Human Rights, and the International Avant-Gardes.