How Picasso Built the Foundation for the Surrealist Movement

John Richardson on the Famed Painter's Friendships with Surrealist Writers and Artists

Pablo Picasso’s contributions to the inaugural issue of Minotaure in 1933 brought him closer to surrealist writers and artists, who had sought from the start to coopt him into their ranks. Indeed, the movement’s very name had been adapted from a term Picasso claimed to have coined to denote, in his words, “a resemblance deeper and more real than the real, that is what constitutes the sur-real.”

Guillaume Apollinaire was the first to publish the term sur-réalisme, in the program for the 1917 ballet Parade—produced by Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes with sets by Picasso—but by the time poet and writer André Breton wrote the first Surrealist Manifesto in 1924, the unhyphenated word’s significance had expanded beyond the sphere of art and aesthetics. Breton defined surrealism as “psychic automatism in its pure state,” and expounded its relation to Freud’s theories on the workings of the subconscious mind. Nine years later, Picasso still complained of how Breton and his followers had misconstrued his meaning: “The surrealists never understood what I intended when I invented this word, which Apollinaire later used in print—something more real than reality.”

Conflicting concepts of surrealism did not prevent Breton from striving to ingratiate himself into Picasso’s life and lure him into the movement. Breton’s blandishments, in the form of public statements, private letters, and published essays, began even before the official founding of surrealism. On July 6, 1923, both men attended the Soirée du Coeur à Barbe (Evening of the Bearded Heart), a program of Dada performances organized by Tristan Tzara at the Théâtre Michel, where the poet Pierre de Massot dared to disparage Picasso by declaring him “dead on the field of battle.” Upon hearing this, Breton leaped onto the stage and demanded that Massot leave the theater. When the latter refused, Breton set upon him so violently that he broke Massot’s arm and had to be removed by police.

Picasso could hardly have forgotten this dramatic demonstration of support when, two months later, Breton begged him to do an author portrait for his soon-to-be-published collection of poems Clair de terre. “I would do anything for you if you would permit a portrait of myself by you to preface [my] book,” wrote Breton, “a long-standing dream that I have never had the audacity to propose to you.”

Breton’s wish was granted in the form of a brilliant drypoint likeness in three-quarter profile that would become the frontispiece to Clair de terre. The time spent with Picasso while sitting for the portrait gave Breton the opportunity to realize another long-standing dream: persuading the artist to sell his cubist masterpiece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon to Jacques Doucet, the collector for whom Breton acted as librarian and art advisor. By the end of 1924, the deal was done and the painting in Doucet’s apartment, further solidifying the bond between the poet and the painter.

Breton’s overtures also succeeded in ensuring Picasso’s involvement in surrealist journals and exhibitions. The first issue of La Révolution surréaliste (December 1924), edited by Breton, featured a photograph of Picasso’s recent sheet-metal Guitar as well as a portrait of the artist by Man Ray. Picasso also allowed Breton to reproduce many of his paintings, including Les Demoiselles, which was properly published for the first time in the July 1925 issue of La Révolution surréaliste. Breton wrote a landmark essay, “Painting and Surrealism,” for the same issue, illustrated solely with Picassos, tying the movement’s future to the artist he venerated. “If surrealism must chart itself a moral line of conduct,” he declared, “it needs only find where Picasso has gone and where he will pass again.”

Although Picasso would never be seduced into joining the surrealist movement, preferring instead to remain on the periphery, he was undoubtedly flattered by the adulation of Breton and his young followers. He also had no compunction about selectively incorporating some of their techniques—eerie lighting, blasphemous references, sexual fetishism—into his own work throughout the 1930s. While he put no stock in their obsession with dreams and automatism, “what Picasso drew from Surrealist ideas,” notes Pierre Daix, “was the liberty they gave to painting to express its own impulses, its capacity to transmute reality; its poetic.” Picasso’s participation, in turn, lent legitimacy to the movement’s nascent publications and exhibitions.

Picasso’s participation, in turn, lent legitimacy to the movement’s nascent publications and exhibitions.

Breton was not the only surrealist seeking an alliance with the artist. In 1929, he had caused a schism by excommunicating from the movement a group of dissidents that included Georges Bataille, a numismatist at the Bibliothèque Nationale and the author of the sexually transgressive novel Histoire de l’oeil (Story of the Eye). Over 90 years after its publication, the Sadeian perversity of Bataille’s novel, in which a female protagonist pleasures herself with the detached eyeball of a dead priest, still shocks.

Active hitherto only on the fringes of the movement, Bataille became a leading renegade in April 1929 when he founded the journal Documents, recruiting as contributors most of the other dissidents alienated by Breton. While Breton relished his role as “the Pope of Surrealism,” Bataille described himself as the movement’s “old enemy from within,” and considered Documents a “war machine against idealism,” particularly the idealization of art, poetry, and the unconscious that distinguished La Révolution surréaliste as well as Breton’s next journal, Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution.

Underlying the editorial policy of Documents was Bataille’s concept of “base materialism,” which destabilized cultural conventions, high and low, for an unflinching look at violence, crime, religious cults, and sexual taboos. These were some of the subjects covered by Documents in erudite essays on archaeology, ethnography, fine art, and popular culture. Base materialism also informed the journal’s treatment of Picasso’s work. In the second issue, Michel Leiris, the artist’s friend and Bataille’s close collaborator, wrote that Picasso’s painting was too terre à terre (down to earth): “never emanating from the foggy world of dreams, nor does it lend itself to symbolic exploitation—in other words, it is in no sense surrealist.”

Competition for Picasso’s participation enflamed the antagonism between the Breton and Bataille factions of the movement, and spilled over onto the pages of their respective reviews. Not to be outdone by La Révolution surréaliste, Bataille reproduced more of Picasso’s work in Documents than that of any other artist, and dedicated a special issue to him in April 1930. The editor’s contribution to this Hommage à Picasso was a short philosophical text titled “Soleil pourri” (“Rotten Sun”), in which Bataille sought to align Picasso with the founding principles of Documents by finding in his work “the search for that which ruptures the highest elevation,” and “the elaboration and decomposition of forms.” In that vein, Leiris contributed a poetic tribute to the artist filled with the kind of visceral imagery that would, as we’ll see, distinguish Picasso’s own writing five years later:

Everyday implements

excrete stars

and the stars do the same right back

They clear their bowels of gutted fruits

and bodies consumed on the off chance

out of the cynical-eyed window

whose damp woodwork spies

Seemingly subdued and withdrawn, Leiris was a man of immense intellect and courage. He had met Picasso in spring 1924 through Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, the artist’s pre–World War I dealer and the publisher of Leiris’s first book, Simulacre. The following year Leiris married Kahnweiler’s stepdaughter, Louise Godon (called Zette), who would take over Kahnweiler’s gallery in 1941. Though stable enough, the Leirises’ union was complicated by the severe neuroses and sexual hang-ups rooted in the childhood traumas laid bare in Leiris’s 1934 autobiography, L’Âge d’homme. Once an active contributor to La Révolution surréaliste, he had been purged along with Bataille from Breton’s circle of surrealists in March 1929. Several months later, in a bout of depression and alcoholism, Leiris appeared on Bataille’s doorstep at five in the morning asking for a shaving razor with which to castrate himself. Bataille put him off with the excuse that he only used an electric, and advised his troubled friend to see a psychoanalyst.

It was also while working with Bataille in the editorial office of Documents that Leiris made the acquaintance of Marcel Griaule, one of the founding fathers of anthropology in France. Despite Leiris’s total lack of experience in the field, Griaule invited him to join a state-sponsored expedition across equatorial Africa to gather cultural artifacts for the Trocadéro Ethnographic Museum.

Embarking in May 1931, Leiris became the secretary-archivist for the Mission Dakar-Djibouti, responsible for maintaining the logbooks and making inventories of objects acquired and photographs taken by Griaule’s team. While also keeping a voluminous personal diary of the journey—published in 1934 as L’Afrique Fantôme—Leiris found time to correspond with Zette, Picasso, and Olga. The encounters with exotic animals and native tribesmen recounted in his letters captivated the imagination of young Paulo, who liked to pretend that he was part of the expedition. Picasso, too, was amused by news of Leiris’s African adventures, sending him a postcard from Boisegeloup on which he drew an ostrich, a rhino, and a giraffe walking the streets of the French village. On February 20, 1933, when Leiris and his colleagues returned to Paris after two years abroad, Picasso was among the crowd waiting at the train station to welcome him home.

__________________________________

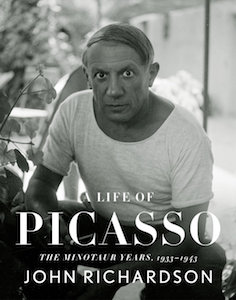

Excerpted from A LIFE OF PICASSO: The Minotaur Years: 1933–1943 by John Richardson. Copyright © John Richardson Fine Arts Ltd. by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

John Richardson

John Richardson is the author of A Life of Picasso (3 volumes; the first volume won the 1991 Whitbread Book of the Year Award), Sacred Monsters, Sacred Masters, and books on Edouard Manet and Georges Braque. Richardson was appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth in 2012. He died in March 2019.