To All the Gays of Seoul: On Translating Sang Young Park

Anton Hur Considers the Importance of Feeling Fully Seen

The traffic began getting bad at Hannam-dong. I hopped out in front of the CJ Building and ran the rest of the way to G—.

*Article continues after advertisement

I screamed when I first read those two sentences, in pure delight of recognition. What club-going gay in Seoul hasn’t done this: ridden a taxi into Itaewon, abandoned the taxi at this exact bottleneck in Hannam-dong, and ran the rest of the way to G—? As a Korean gay man in Seoul just a little bit older than Sang Young himself, I can even tell you the letters obscured by the em-dash in G—. The club has a different name now; in fact, I think G—was several names ago.

Of all the sentences in this book, some were relatively easy to translate, while many presented a plethora of conundrums and points of discussion that could easily fill the limit I’ve been given for this note. But the sentences I most wanted to discuss were these two. They took hardly any time to translate, but I spent a few minutes fretting that no one would know how thrilling it was to see them in a novel, this wink to All the Gays of Seoul.

Because until I read these sentences—nay, until I read Sang Young Park—I had no idea how much I’d subconsciously craved for someone to put my experience of my world in my time into print, to give my brief life here and now the sacred consecration of literature.

My friends were all in their twenties and would never say no to a free drink, and thus we “T-ara members” soon found ourselves strutting down Itaewon-ro in formation. I’d labeled our group chat after the girl group T-ara because there were six of us and I’m so very creative at naming things. I was the second shortest of the group and had a seriously nasal singing voice. Naturally that made me So-yeon, but that’s not important; what’s really important was that we had descended upon the club and were making our entrance.

Unlike many other Korean-to-English literary translators, I’m not an immigrant or part of the diaspora, nor did I go overseas for college or grad school. I am a Korean man living in Korea, and I’ve been living here for 30 years. Many of the experiences Young had in this book, I had too. I am sure I danced in the same clubs in Itaewon, drank at the same bars in Jongno, brushed past him on Homo Hill as I tried not to spill my Black Russian, and probably had gamjatang at the same restaurant at four in the morning as we waited for the subway to start running again. We even both had our military service cut short for medical reasons, although mine involved a lot more orthopedic surgery.

And yes, on some meaninglessly literal level, I know Young is a fictional character. But he is so real to me on the page, and the places and situations so vivid and familiar, that I feel he has stepped into my own memories of this big, gay city we call Seoul, not to mention that other big, gay city we call Bangkok where I happen to have lived during high school and still visit every year. Surely Young and I were aboard the same ferry on the Chao Phraya River at some point, watching the rain thunder down on the silt-rich water. I can see him in his shorts (Korean tourists always wear shorts in Bangkok) and I can see Gyu-ho, too. They look befuddled as they stare out at the rain (the late rainy season rain), perhaps thinking not just about this sudden downpour, but also of their relationship and the murkiness of its future.

Feeling like we were on a cruise, we squeezed into two of the tiny plastic orange seats, our shoulders smashed against each other. The boat shook more than I expected as it started to move, and it pitched forward with a groaning sound. We were only five minutes into our cruise up the river when rain clouds suddenly darkened the sky.

–It’s going to rain? You said it was the dry season.

–I said it was the late rainy season.

–Isn’t that the dry season?

–I guess even the late rainy season is still the rainy season.

When I first translated Sang Young’s work, he had never published a book and no one had translated him; by the time I was working on this novel, other translators were trying to steal him from me. You see, he was a bestseller now, a critical and commercial success, and they wanted to get in on the action. One eminent translator, whom people respect way too much, sneered that I had chosen to translate him because queer literature was “in” now.

I spent a few minutes fretting that no one would know how thrilling it was to see them in a novel, this wink to All the Gays of Seoul.

But l never translated him because he was a bestseller; indeed, he was nothing of the sort when I first encountered “Tears of an Unknown Artist, or Zaytun Pasta” in its first appearance in Munhakdongne’s quarterly magazine. He didn’t even have a book published. So no, I did not translate him because he was commercially successful or because queer was “in” (whatever that means).

I translated him because no one had told this story before, and it was my story. No writer had ever inhabited the same place at the same time as me, breathing the same air and thinking the same thoughts. I didn’t care if Sang Young Park was an obscure new writer and the story I wanted to translate had an impossible title and came out at an unpublishably long 17,000 words in translation, meaning no magazine would want to take it on in its entirety (except the fantastic Words Without Borders). I’m not an adventurous person at all, but I had to break several of my own rules regarding funding procurement and working on spec to bring Sang Young into English—and indeed, into translation itself—for the first time.

Would I advise other translators to do the same? Not at all. And maybe there’s another translator out there who would’ve done a better job, I mean, it’s a big universe. But that translator did not exist in the right place at the right time, namely, the same place at the same time.

But I did.

Lightning flashed and thunder rolled, and thick strands of rain beat atop the roof of the boat. Rainwater seeped through the edges of the tarp, and it fogged over. We gripped each other’s knees and endured the rocking. The feeling of Gyu-ho’s hot knee in my hand made me feel strangely sleepy. The tossing of the boat didn’t make me anxious at all. I had my hand on his knee until my palm was wet with sweat. Saying his knee was hot, Gyu-ho removed my hand and placed it in his own icy palm.

__________________________________

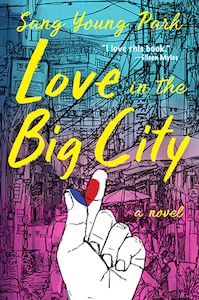

This essay originally appears as the translator’s note exclusive to the Tilted Axis Press edition of Love in the Big City.

Used with the permission of the publisher, Grove Press. Copyright © 2021 by Sang Young Park. This publication was facilitated with the support of the Literature Translation Institute of Korea.