How Patti Smith Brought Rock 'n' Roll to New York Poetry

The Arty Rimbaud in a Spotlight

In a candid interview with Victor Bockris published in 1972, Patti Smith laid out her goals as they related in part to her negotiation with the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s. Bockris seemed particularly interested in highlighting how Smith was “totally ignoring” the downtown literary scene despite her all-access pass to that desirable coterie. Bockris continued pressing Smith on this question by asking her point blank about whether she could actually learn anything from the downtown poets. The answer was an emphatic “no,” in large part because of what Smith argued was the St. Mark’s poets’ inability to perform charismatically and because of what she perceived to be the poets’ boring lifestyles. Name-checking rock ’n’ roll gods including Jim Morrison, Bob Dylan, and the Rolling Stones and identifying Humphrey Bogart as someone she got “excited about,” Smith acknowledged, “I’m not interested in meeting poets or a bunch of writers who I don’t think are bigger than life. I’m a hero worshipper.”

Smith’s candor here was refreshing. Not for her the collating parties, the group readings, the self-published small-circulation anonymous and pseudonymous publications. Rather, rock ’n’ roll as a model for performance poetry helped Smith reestablish and celebrate the divide between privileged stage and underwhelming page. Rock ’n’ roll, particularly by the late 1960s and early 1970s, had become a vehicle for deification, as the small-scale clubs, halls, and streets made way for the imperial grandeur of the amphitheater and festival. While much could be said for Smith’s starting her music career in tiny clubs like CBGB, we should not forget that the end goal was to play—as the Patti Smith Group eventually did—in large arenas in the United States and Europe. That Smith wanted to imbue poetry with the bigger-than-life theatrics of the rock ’n’ roll stage show suggests a creative intervention into and critique of the avant-garde poetics and attendant principles of the period.

Employing the kind of terminology we associate with rock ’n’ roll, Bockris continued his interview by asking Smith which poets she would like to “tour” with. Naming Jim Carroll, Bernadette Mayer, and Muhammad Ali as her chosen three, Smith explained that it was their ability to perform captivatingly that was especially attractive to her. Carroll was particularly celebrated because his life as a heroin addict, hustler, and bisexual marked him out as a true Rimbaudian poete maudit in distinction to the other St. Mark’s poets, whom Smith dismissed as “so namby pamby they’re frauds.” Smith took especial delight in mocking the St. Mark’s poets’ propensity for writing O’Hara-style “I do this, I do that” poems “about today at 9:15 I shot speed with brigid sitting in the such and such.”

It seems here that Smith looked to poetry not so much for what the art had to offer her as a model for her songwriting but for what the discourse of poetry could provide her with in terms of thinking about how to make actual lifestyle and performance choices. In a related interview with Bockris, for example, Smith acknowledged why she was initially drawn to French poetry and fiction. In response to Bockris’s question—“Why are your influences mostly European: Rimbaud, Cendrars, Celine, Michaux?”—Smith replied that it was the French writers’ biographies that proved so seductive for her: Their wild lives couldn’t be matched by the contemporary crop of American poets. Again, show business was at the center of her critique, as she went on to celebrate how Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg revitalized a performance culture that had died out following the death of Oscar Wilde.

Smith’s revisionary history is, of course, arguable. That said, what is revealing and useful in her account is how Smith marked the purported rebirth of muscular performance poetry. Ginsberg, perhaps the most recognizable American poet of the 1960s, was synthesized with Bob Dylan, the pop star most aligned, if problematically, to poetry. The two men had been friends for years, forming a kind of mutual-appreciation society that found Ginsberg handing the mantle of Beat spokesperson over to Dylan. Dylan, for example, famously featured Ginsberg in the opening credits to D. A. Pennebaker’s film Don’t Look Back (1967), which situated Ginsberg all the more firmly in the pop firmament. In 1975 Ginsberg took Dylan to Jack Kerouac’s grave in Lowell, Massachusetts, where the two men read from Kerouac’s 1959 poem Mexico City Blues and sang together, a scene that was included in Dylan’s film Renaldo and Clara (1978).

These kinds of exchanges blurred the lines between poet and pop star all the more, as each figure profited from the cultural and popular capital attendant to their increasingly fluid roles. Who was the pop star? Who was the poet? Could we—should we— even bother separating the two roles anymore? “I don’t want to get away from poetry,” Smith insisted to Lisa Robinson in early 1975, “but there’s no reason why the two have to be separated. I think I’ve proven it with what I do with ‘Land of a 1000 Dances’ . . . it’s totally impossible to distinguish what is poetry from the poetry in that and the rock and roll. They’re so integrated.”

Smith had a point. By 1970 Ginsberg was already issuing records of his weirdly Yiddische versions of Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience, while Dylan in 1971 finally got around to publishing Tarantula, his widely bootlegged book of prose poems, with the venerable publishing house Macmillan. Smith wanted in on the “integrated” model personified by Ginsberg’s and Dylan’s works and friendship, and she went far in expanding their hybrid poet/performer prototype. As early as 1973, a full two years before Smith released her first album, Horses, Ginsberg saw the potential power in Smith’s efforts to collapse poetry into pop, pop into poetry. “What Patti Smith seems to be doing,” Ginsberg proffered, “may be a composite memorized, and the American development of Oral Poetry that was from coffee houses now raised to pop-spotlight circumstances and so declaimed from memory again with all the artform—or artsong—glamour that goes along with Liddy Lane . . . maybe. Then there’s an element that goes along with borrowing from the pop stars and that spotlight too and that glitter. But it would be interesting if that did develop into a national style. If the national style could organically integrate that sort of arty personality—the arty Rimbaud—in its spotlight with make-up and T-Shirt.”

The “arty Rimbaud,” bathed in the glow of the stage lights, was the way forward for poetry as far as Smith was concerned. The namby-pamby “I do this, I do that” New York School poets didn’t stand a chance in Smith’s ever-starrier poetic firmament. By the early to mid-1970s, as the music journalist Nick Tosches remembers, Smith’s poetry-cum-rock ’n’ roll performance had marked her out as something special—something that represented a serious break with the poetry crowd.

She was feared, revered, and her public readings elicited the sort of gut response that had been alien to poetry for more than a few decades. Word spread, and people who avoided poetry as the stuff of four-eyed pedants found themselves oohing and howling at what came out of Patti’s mouth. Established poets feared for their credence. Many well-known poets refused to go on after Patti at a reading, she was that awesome.

And certainly by 1975, the year that brought the world Horses, Smith was actively cutting ties with the poetry community from whose stage she emerged. At a 1975 concert Smith gave at New York’s Other End club (known formerly as the Bitter End), none other than Bob Dylan “stuck his head in the dressing room afterwards, a madhouse of journalists and photographers. ‘Any poets around here?’ [Dylan asked]? ‘I don’t like poetry anymore,’ Smith blurted. ‘Poetry sucks!’ ”

__________________________________

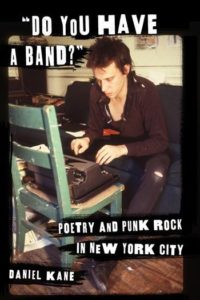

From “Do You Have a Band?”: Poetry and Punk Rock in New York City. Used with permission of Columbia University Press. Copyright © 2017 by Daniel Kane.

Daniel Kane

Daniel Kane is Professor in English and American literature at the University of Sussex in Brighton. His books include We Saw the Light: Conversations Between the New American Cinema and Poetry (2009) and All Poets Welcome: The Lower East Side Poetry Scene in the 1960s (2003).