How One of My Favorite Songwriters Came Along and Saved My Novel

When Don Lee Sent a Longshot Email to Will Johnson

In 2016, I reached out to Will Johnson—a stranger at the time—because I was in desperate need of professional help.

A novel of mine, titled Lonesome Lies Before Us, was scheduled to be published the following year. It was about an alt-country musician who’d never quite made it, and there were three spots in the book where I needed to put down some lyrics, which were supposed to convey that the character was a good songwriter. The problem was, I wasn’t a songwriter. I had only a rudimentary grasp of music; I played a little guitar, that was all. I took a stab at writing some verses. They were, in fact, the first lyrics I’d ever attempted, and they were, I knew, terrible. I needed someone to save me.

I cold-emailed Will Johnson through the general address on his website. I’d been a fan of Centro-matic for years, but I thought of him because I was watching a lot of videos of singer-songwriters doing solo acoustic shows during that period, and some of Will’s performances, particularly of songs like “Just to Know What You’ve Been Dreaming” and “You Will Be Here, Mine,” were killing me. They exuded just the sort of yearning and melancholy that I wanted my character’s music to possess. There was another reason I chose to petition Will, too: I knew that he had been an English major at the University of North Texas in Denton, and I suspected that maybe he’d taken a creative writing class or two there, maybe had harbored dreams of becoming a poet or writer himself in his youth, and thus this project might appeal to him.

I waited. I didn’t know if I’d ever get a reply. Then, ten days later, Will emailed me back. Bob Andrews, the artist manager at Undertow Music who arranges his living-room shows, had forwarded my message to him, and Will said to me, with what I would learn is his usual gentle humility, “I don’t know how much I’d have to offer, but would be happy to try and help. The road sometimes offers some quiet and focus time, particularly on the drives, so maybe I could dig into this some then.”

About two weeks later, he sent me his revisions of the title song. These were my original lyrics:

Lonesome lies before us

Whatever country we’re in

We search the world for memories

There’s never enough to begin

I’m not ashamed I miss you

It’s the same old sin

I look for you city to city

Though I’ll never see you again

And here’s what Will Johnson did to them:

Lonesome lies before us

Whatever place we’re in

We search this world for memories

Unfinished, that never end

The distance always owns us

And what it was to be free

The distance always showed us

Our own frayed reverie

I’m not ashamed that I miss you

I’ve got my same old sins

I look for you in all the spaces

I always wished we’d been

He had composed an entirely new second verse. The other changes were not as obvious, but made a huge difference. For one, I had succumbed to the whole rank-amateur trap of trying to rhyme everything, and he corrected that inept notion. For another, he refined the stresses and cadences of the lines—their rhythm. Most importantly, he added subtlety and mystery to what had been a bland, clumsy, overt song, transforming it into something that was almost passable. It was, in essence, a master class in songwriting. Needless to say, I was thrilled.

Six months later, I got to thank Will in person. He was driving through the Northeast on another living-room tour, and he was stopping in Baltimore, performing at his friend Scott Vieth’s house. Going to the show a little early to meet Will, I didn’t know what to expect. I fretted that he might be aloof or pretentious or awkward. He was nothing of the sort. He was polite, unaffected, and friendly. Nice. He was also funny and smart and interesting. A regular guy and a thinker, rolled into one. We drank a couple of beers and talked, and then he put on a baseball cap and sat down in a chair in front of an audience of 50 or 60 people, no mics or amps, no accompaniment, just himself and his Martin 000-15, and knocked us all out.

I worried he might embarrass himself, just as I had been afraid of embarrassing myself with my turgid song lyrics.

Over the course of the next few months, he would help me further with the novel. I really needed someone who was a working musician to fact-check the parts of the book that pertained to music. I worried I’d come across as a fool to those in the know. I asked Will if he’d skim over parsed sections of the novel that referred to the music business and production and DIY recording. He did better than that: He read the entire manuscript. “I think it all looks good,” he reassured me. “Coincidentally enough I have also been tracking on my classic Tascam 424 (Mach 3) this week, so it’s all hitting home!”

Then I followed up with a seemingly offhand question. I asked if he’d sung the words to himself when he’d revised my lyrics. Yes, he said. “I’m in a pattern of testing myself with line capacity some lately, seeing if I can elongate some lines and add more detail here and there. Sometimes it works and sometimes it sounds too cluttered. Just trying to break some old habits of always taking the easy route; regularly feeling like I have to keep things in line and tidy.”

I’d love to hear the melody lines, I told him, then I confessed that it’d be great promo for the book if he’d record a few snippets for me.

It took him a while, but eventually he sent me an MP3 of himself singing “Lonesome Lies Before Us,” which he’d recorded on his iPhone in his garage art studio. It was wondrous—haunting and beautiful. I’d never imagined the lines being sung in such a way. My publisher uploaded it to YouTube, and then Will did us another favor. He was driving from Chicago to Minneapolis on another living-room tour, and the timing worked out so he could join me for an appearance at Boswell Books in Milwaukee, where, to everyone’s delight, he did a little Q&A with me and played some songs.

The next year, the tables turned. I found out on the internet that he had received an advance contract to write a book for Goliad Media, a production house in Denton that releases art, books, and music. I had been right. He had harbored dreams of becoming a writer himself. He was a bit abashed when I told him I had heard the news. At that point, he didn’t even know what kind of book he wanted to produce, although he’d been drafting a few things. “I’m trying to be more disciplined about the writing,” he said. “Not so much in terms of the looming ‘book,’ but simply for the discipline of it. A few memoirs brewing now, and a short story or two that I’m a little stuck on, honestly. If anything it will probably be a short, two-section/hybrid book. Maybe something for the merch table. Trying not to overthink things (as I was at first), and just live in the joy of writing these days. The rest will hopefully sort itself as I go.”

I offered my services as an editor to Will, saying I’d be happy to read anything he sent to me. Truth be told, I expected his stuff to be bad. He had no training or experience writing prose, especially longform. I worried he might embarrass himself, just as I had been afraid of embarrassing myself with my turgid song lyrics. I thought he might need to be saved from humiliating himself.

Without Will’s permission, I submitted it to the editors of the journal American Short Fiction for consideration, and they enthusiastically responded.

About six months later, he forwarded three short passages to me. He said he’d been writing in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, his first time there. “These are just beginning shards and I’ve got to get to know these folks better this week without the (welcome) distraction of mountains and great food and drink just out my window. Work some things over and put them in some predicaments, I suppose.”

Instead of the hybrid I’d expected—a mishmash of memoir, poetry, journal excerpts, lyrics, or vignettes—what Will sent to me was fiction. Three bona fide pieces of narrative fiction that were linked by recurring characters (“these folks”) named Melinda, Parker, and Ben. And instead of being bad, or embarrassing, or potentially humiliating, the passages were magnificently crafted, natural, pure, with a fluid narrative. Will Johnson was a writer, the real deal.

One of the pieces could work as a standalone short story and was eminently publishable, I thought. Without Will’s permission, I submitted it to the editors of the journal American Short Fiction for consideration, and they enthusiastically responded in less than two weeks, saying they wanted to accept it. Here he was, being validated as a fiction writer by one of the best literary magazines in the country, just like that. I got a great deal of pleasure calling Will to tell him what I had done without his knowledge.

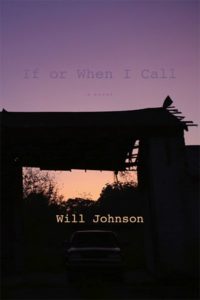

Two years later, he sent me a 300-page, 60,000-word manuscript for a novel entitled If or When I Call. I read it and was floored. It seemed impossible that Will hadn’t gone through an MFA program in creative writing and wasn’t on his fourth or fifth book. He wrote with the smoothness and assurance of a seasoned veteran. What impressed me the most was that he wasn’t trying too hard. He was confident enough in his story and characters not to succumb to melodrama. He was simply relating a story about ordinary people who were trying to make a life for themselves, hoping for a little solace along the way. The book was exquisite, stirring, and soulful.

Will Johnson had schooled me once again. Unlike me, he didn’t require any lessons, and he certainly didn’t need saving. He showed me that he was perfectly capable of taking care of everything on his own.

__________________________________

Will Johnson’s novel, If or When I Call, is available via IndieBound and Bookshop.

Don Lee

Don Lee is the author of the novels The Collective, Wrack and Ruin, and Country of Origin, and the story collection Yellow. He has received an American Book Award, the Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature, the Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction, the Edgar Award for Best First Novel, an O. Henry Award, and a Pushcart Prize. He teaches in the MFA program in creative writing at Temple University and splits his time between Philadelphia and Baltimore. His new novel, Lonesome Lies Before Us is out now from W. W. Norton.