How My Passion Project Led to Burnout: On the Bittersweet Rewards of Creative Risks

Leigh Stein Considers Life as a Working Writer and the Challenges of Forming an Alternative to AWP

In 2016, I was executive director of a nonprofit writing organization and I earned $38,922 before taxes. That number is not my salary—it’s the sum of multiple income streams, as I hustled to support my passion project. I taught writing workshops in New York City ($7,988), did freelance proofreading and copyediting for a startup ($8,348), wrote freelance articles ($4,772), and received part of a book advance ($5,814). For my role as executive director, I was paid a stipend of $12,000. I was able to get on my partner’s health insurance plan (the year before, I’d been on Medicaid).

I clocked 859 hours for the nonprofit in 2016. I organized a conference called BinderCon, which happened in New York every fall and Los Angeles every spring, drawing about 1,000 writers a year. My co-founder and I raised hundreds of thousands of dollars in corporate sponsorships and foundation grants (each two-day conference cost about $80,000 to put on). To make our conferences more accessible, I helped to organize viewing parties of our livestream all over the country. Our generous scholarship program included travel and childcare stipends. I managed a bicoastal, largely volunteer staff of 24 people. I made $14 an hour.

If I’d written a personal essay about my financial situation, I could have qualified for a scholarship to my own conference.

One of my inspirations for launching BinderCon was to offer an alternative to AWP, the country’s largest creative writing conference (in 2015, there were 14,000 attendees). If you present at AWP, you have to purchase a ticket (we comped tickets for all our speakers). Since AWP is a gathering of students and professors from the country’s 200 creative writing MFA programs, some of the programming felt insular to me: writers who teach writers to write for other writers talking about writing. What about getting paid to write? “That’s not what an MFA program is for!” I hear you saying. Okay, but that’s what I wanted to offer with BinderCon: professional development for writers, whether you were a journalist or a novelist, or a TV writer. We offered speed pitching with literary agents and magazine editors, and workshops on op-ed writing and making a living as a freelancer.

BinderCon LA Organizing Staff. Photo by Rebecca Aranda.

BinderCon LA Organizing Staff. Photo by Rebecca Aranda.

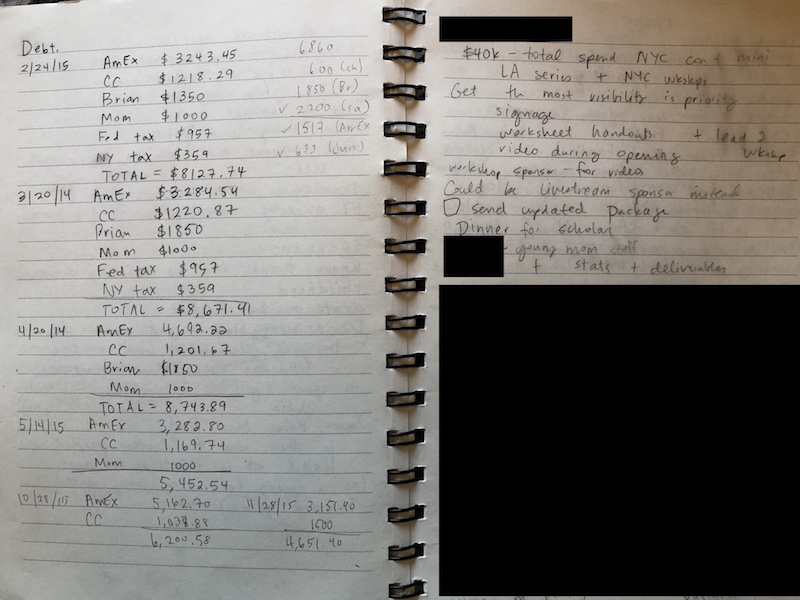

I went into debt in order to build this. Here’s a page from a notebook I kept during my BinderCon days. On the left page is my debt: credit card debt, taxes owed, and debt to my mom and boyfriend. I feel more shame about borrowing money from them than I do about anything else. I’ve been working since I dropped out of high school at 17. This is the only time I can remember that I was so out of options that I asked my mom for a loan.

On the facing page are the notes I took at a meeting with a major women’s media brand, as we built a $40,000 sponsorship package for them. This time in my life was a surreal montage of power lunches to ask for tens of thousands of dollars, and me at TJ Maxx charging a polyester Ivanka Trump blouse so I’d have something professional to wear in my photo op with Lisa Kudrow.

BinderCon LA 2016 with Lisa Kudrow. Photo by Nicol Biesek.

BinderCon LA 2016 with Lisa Kudrow. Photo by Nicol Biesek.

This was the heyday of the girlboss. Friends who knew how broke I was advised me to hit the women’s empowerment conference circuit (e.g., Create & Cultivate, where “the next generation of curious creatives…enlighten, entertain and inspire” or BullCon, “where there is no reason you can’t have a roundtable on sexism in the workplace followed by champagne”) and use the fact that the Washington Post had named me a “leading feminist” to my advantage. If I leveraged my personal brand as a female founder in her early thirties, I could go around the country talking about gender and racial inequities in the writing industries, using data collected by organizations like VIDA and the Writers Guild, and get paid to be a feminist thought leader. I did do a little of this—I moderated a panel on women screenwriters called “Chicks and Bics.” When I asked about the title, I was told that was the one panel at the screenwriting conference about women writers. They offered it every year with the same title. (I wasn’t paid for this speaking opportunity, but I did receive a VIP gift bag with a bottle of prosecco.)

My situation with BinderCon is unusual: most writers don’t start an $80,000 conference as a side project. But I think a lot of working writers can relate to the juggling act of labor: what work do I have to do in order to get paid, so that I can do the work that pays nothing?

By the spring of 2016, I had developed repetitive stress injuries in both wrists from overwork. I wore wrist braces to BinderCon LA and took them off when I got my picture taken with Lisa Kudrow. Moderating our private Facebook community of 40,000 writers was taking a toll on my mental health and I went back on anti-depressants for the first time in years. Wine at night became nonnegotiable; drinking was how I numbed out while scrolling toxic conflict threads. I gained fifteen pounds.

All the idealism I’d had when I started the conference was gone. I became cynical about online feminist activism: how easy it was to publicly shame or socially exclude someone for disagreeing with you or your clique. At the same time, I found myself fixating on the mistakes, incompetence, and ignorance of other people, to shield myself from my own feelings of worthlessness. I was easily irritated; a single email could ruin my day. I only felt awake when I was running on adrenaline from the latest conflict in the Facebook group (imagine the high drama of “Bad Art Friend” unfolding on a weekly basis in an online community that you’re in charge of moderating). I read self-help books on productivity and leadership, trying to optimize myself back to being a Highly Effective Person. I didn’t realize I was suffering from burnout.

I created a fundraising strategy doc for 2017, to raise enough money that I could earn a $40,000 salary. Then I had a brilliant idea: I could fundraise so that someone could take my place as executive director.

Ultimately, I realized no one would want my job. The challenges facing the organization were bigger than financial. I felt like I’d personally failed as a leader, but I wasn’t healthy enough to continue. I resigned in May 2017.

“I don’t think I’ll ever be able to write again,” I told my partner.

“You will,” he said.

I started writing a short story about a burnt-out female founder who goes to a wealthy investor’s house in the country for a digital detox and once she’s there, she starts seeing things in the wallpaper.

That story was the seed of my novel Self Care, which came out last summer, just in time for the end of the girlboss. According to Vox, I have become “the world’s foremost authority on the girlboss.” I’m the only journalist on the girlboss beat who was once a female founder herself.

What work do I have to do in order to get paid, so that I can do the work that pays nothing?

BinderCon never happened again after my resignation. In the years since, I paid off all my debts. I opened a retirement savings account. I started a small business and have successfully resisted all advice to scale up.

When I recently saw how much revenue Grub Street, a nonprofit organization, is bringing in from its writing workshops and conferences, it triggered some bitter feelings. I thought about what I would have been able to accomplish with BinderCon, if I hadn’t been in such a difficult position financially. I also remembered how uncomfortable I felt making the fundraising pitch, how I never got good at the dance.

In Self Care, my main character Maren is the underpaid executive director of a nonprofit before she goes full-on girlboss.

As executive director, my job was to eat salad with rich women from all over the great island of Manhattan, compliment their avant-garde jewelry and trend-driven philanthropic work, and then beg them to come on as sustaining donors for a series of anatomically accurate yet artistically rendered vaginal sculptures. Every lunch ended with me half-heartedly reaching for the check until they stopped my hand. It was the least they could do. No one ever wanted to come on as a sustaining donor at this time, but there was always someone else I should really talk to; they would make an e-intro and I had to thank them for their generosity before moving them to BCC. My future was an infinite horizon of fine dining in vain.

“I’ve built this organization that’s supposed to be changing the world, but I’m killing myself,” I told Devin. “I’m killing myself for other women.”

She placed a hand on my forehead like a blessing. Her palm was surprisingly warm and calming. “Your pain is sending you a message right now,” she said. “Your pain says it’s time to pivot.”

Creating something from scratch—whether that’s a conference, a company, or a novel—means taking a risk. There’s no way to know if you’ll ever see a return on the time, energy, and money you’ve invested in pursuing a dream. But when I look back on my years organizing BinderCon, I have zero regrets. I’ll never have to wonder what would have happened if I’d actually followed my instinct to start something—because I did start something. I took that risk. I tried.

Leigh Stein

Leigh Stein is a writer interested in what the internet is doing to our identities, relationships, and politics. She is the author of five books, including the critically acclaimed satirical novel Self Care (Penguin, 2020) and the poetry collection What to Miss When (Soft Skull Press, 2021). Her non-fiction writing has appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the New Yorker online, Allure, ELLE, Poets & Writers, BuzzFeed, The Cut, Salon, and Slate.