How My Novel Disappeared—And Why it Came Back

Lucy Ferriss on the “Strange Miracle” That Brought Back Her Story

You know that feeling when you’ve stacked a pyramid of chairs and made it up in sight of the pinnacle, and you feel that little wobble underfoot? Okay, maybe you’ve never done that; I haven’t. But in 1997, I had won two national awards and an NEA fellowship. I’d hung out with the more and less famous at places like Yaddo and the MacDowell Colony. I had landed a tenured job at a prestigious college in upstate New York. My forthcoming novel, The Misconceiver, was the second in a two-book contract with Simon & Schuster. It boasted a gorgeous cover, solid blurbs, and a story no one had yet had the nerve to tell.

Then came the wobble.

Late one night, just as the book launched, I came home to a letter from Eric Raymond, Simon & Schuster’s lawyer. He wished to speak with me as soon as possible. I was being sued for libel. Could I explain my use of the last name “Gwilliam” for a pastor mentioned in Against Gravity? I sat in the dark living room and felt the chairs wobble. According to my contract, I was on the hook for half the settlement of any lawsuit against me and Simon & Schuster, and we were being sued for a million dollars.

During the 10 years of writing Against Gravity, I had married, moved four times, held five different jobs, birthed two children, earned a PhD., and turned a story collection into a novel. One of those stories had emerged from a tiny local article about a church whose pastor was an Australian former boxer and ex-convict named Gwilliam. Had anyone asked me where I’d gotten the name, I would have said, “Oh, I have to change it!” But no one had asked, and by now I’d forgotten that I had not completely invented the hapless pastor. Who would have thought that he’d read my novel?

He hadn’t, as I learned when I called Eric Raymond. Rather, Rev. Gwilliam and his wife had divorced; Rev. Gwilliam, diagnosed with terminal cancer, had moved to Florida; Mrs. G had moved to within ten miles of the college. At the computer repair shop where she worked, a customer had spotted her nametag and said, “That’s an unusual name. I just read it in a novel!”

The suit was specious, Mr. Raymond told me. The fictional Pastor Gwilliam had no fictional wife. You cannot sue on behalf of someone else. Nothing in the novel defamed the character, and in any case it was fiction. Plus, he said cheerily, the pastor would die soon, and you cannot defame the dead. There was only one problem. It was the publisher’s policy not to distribute books by any author currently being sued.

“But I have a book just coming out.”

“It’ll take six months or so,” he said. “Tops.”

*

The idea for The Misconceiver had come to me in the shower, after reading the proofs for Against Gravity. At the center of that book had been a teenager so obese that no one could tell she was pregnant. It occurred to me that I wasn’t done with this subject; that, as a woman who had terminated two pregnancies and given birth twice, I had another story to tell. We had begun Bill Clinton’s second term, with a Republican-led Congress and postcards warning that Roe v. Wade, shored up four years earlier by Casey, was in peril. I was a judge’s daughter. I knew that rulings made their way slowly through the courts, with effects that rippled gradually across years. What would it mean, really, to lose the federally guaranteed right to abortion?

I got out of the shower with a voice in my head and began to write. The voice belonged to a young woman, Phoebe, who would be born at the millennium, whose mother would be killed by a bomb at her abortion clinic just before the 2006 Roe overturn. Five years later, with the right wing ascendant, Congress would pass the Human Life Amendment to the Constitution.

I dug into legal opinions in the library archives. Privacy, the lawyers wrote, was the weak point in Roe. Argue successfully that no such right exists in the Constitution, and not only abortion rights fall; so do rights to birth control, to sexual preference, to in vitro fertilization. Phoebe had grown up in this world, I realized as I wrote. Her older sister, arrested and imprisoned for performing abortions, would have died in custody. Her loyalty to family would come into direct conflict with the ethos of her world, where common wisdom held abortion to be murder, same-sex relations abhorrent, and Christianity the founding principle of her nation.

Then, as now, no one would want to say abortion. What would they say in the year 2026? At Yaddo, I looked up the word in the huge 1959 Webster’s and found four synonyms: mistake, misconception, monstrosity, and failure. By process of elimination, I had my title. What I didn’t have was the actual future. I predicted that technology would grow more invasive, with computers shrinking to pocket size; I called this device a minilap. I assumed electric vehicles would be common, phone calls face-to-face. I did not foresee Wi-Fi, same-sex marriage, the fall of the twin towers.

When The Misconceiver launched, it received glowing reviews—but bookstores had no books for six months, by which time readers had moved on. Within two years, the title was out of print. I bought 50 copies with my author discount; the rest were remaindered or pulped. Over the years, whenever the fragile status of Roe v. Wade came up, calls came to republish the book. I didn’t know how to move forward—revise the book to include the internet? Set it farther into the future?

Then came the June 2022 Dobbs decision.

I put my few books up on Amazon and started sending the proceeds to reproductive rights organizations; my local bookstore took some copies on consignment. Finally Ron Charles, book critic at the Washington Post, found the book after he had reviewed a raft of abortion-centered novels. In his newsletter, he wrote: “The Misconceiver is a startling novel in ways that highlight how unsurprising most pro-choice novels are. Ferriss isn’t interested in merely confirming our liberal ideals; she makes us work for them.”

My bookstore called; all the copies had sold within two hours—did I have more? Rare books dealers started buying up the remaindered British paperbacks for more than $200. In my house I found six copies, but Amazon had two dozen orders. I shut the account, apologized to everyone, and emailed the smartest, nimblest publishing house I knew of—Wandering Aengus, which would be bringing out my book of essays next year. “YES!” the publisher wrote back. “Let’s do this!”

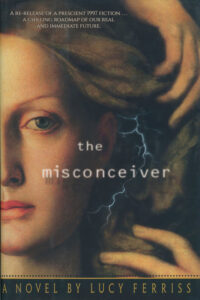

Various hurdles remained. For starters, no manuscript existed. I had saved the novel to floppy disks, all of which were corrupted. I scanned my one remaining book and spent days correcting conversion errors. I was no longer tempted to revise; the original novel had its own integrity, and bloopers about technology paled in comparison to the depiction of a state of affairs whose future is nearer than what I forecast 25 years ago. Next, we needed a cover.

Fortunately, the original artist, Honi Werner, though she no longer designed book covers, was reachable and generously granted us the rights to her design, which I captured by way of an archival library’s high-res scanner. To signal the book’s attention to the Dobbsdecision’s effect on women of color, we complemented the design with a back cover featuring an image that eerily echoed the look of the front. It took endless calls to Amazon for their computer to retire the out-of-print editions in favor of the new publication, but now e-book and paperback have both appeared. And singer-songwriter Kat Eggleston, whose song “The Stranger” walks the same emotional tightrope as the book, agreed to let us use it for a book trailer.

For me, this journey has been a strange miracle—a professional tragedy, followed 25 years later by a political tragedy that has brought The Misconceiver back into print. All my author proceeds continue to go to the fight for reproductive rights. If the book lives on, my hope is that it will one day read like a dystopia that we managed, through grit and struggle, to avoid.

__________________________________

The Misconceiver by Lucy Ferriss is available via Wandering Aengus Press.