How KISS Became a Rock & Roll Phenomenon

Doug Brod on the Haphazard Success of One of

America's Greatest Bands

Beginning in August 1974, KISS recorded two albums in quick succession. Hotter Than Hell, made in L.A., where producers Kenny Kerner and Richie Wise had moved, was a difficult birth for a number of reasons. First, the band’s stockpile of songs had run low, so they needed to write quickly on the road, supplementing the new batch with leftovers from their early days. Additionally, the band members, all born-and-bred New Yorkers, felt out of sorts in the sunny, palm-treed environs, though that didn’t stop them from indulging in the attendant decadent lifestyle, even on a salary of just $85 per week. For the four of them, that meant getting laid, but for Ace Frehley and Peter Criss it also meant getting hammered, which only served to highlight the personality differences that began to generate tension within the group. One night, Frehley damaged his kisser in a drunken car wreck, which led to a compromised photo shoot, resulting in pictures of his half-made-up face in profile.

Perhaps worst of all, the producers failed to capture the sound they wanted. “It was overly compressed and overdriven,” said Wise, lamenting the record’s brittleness. Still, some potent songs emerge from the buzzy haze, including the proto–groove metal “Watchin’ You,” the fizzy power-pop “Comin’ Home,” the supremely nasty rifferama “Parasite,” and the brusque come-on title track. Even soft-headed throwaways like “Mainline,” Sladean boogie-pomp enlivened by an astringent Catman roar, and the Chuck Berry gimme “Let Me Go, Rock ’n’ Roll” end up dazzling. Of the heavier songs, at first blush you would think “Goin’ Blind,” a majestic Simmons dirge with a stinging Frehley solo, is, considering the source, extolling the pleasures of masturbation. But, in fact, it details a nonagenarian’s age-inappropriate lust for a teenage girl and the onset of his age-appropriate sightlessness.

Dressed to Kill, recorded just six months later back in New York, benefited from better production, by the band themselves, though Bogart, who acted as cheerleader, also received credit. Owing to a dearth of record-ready material—with the exception of the delicate-to-deadly “Rock Bottom,” side 1 feels particularly anemic—KISS once again dipped into the Wicked Lester library for smart redos of “She,” now without flute and horns but with way more shredding, and “Love Her All I Can,” which apes the Who by way of the Nazz.

Though neither album made much of a dent upon initial release, KISS’s reputation was growing. And the band toured on . . .

*

“You wanted the best and you got it, the hottest band in the land . . . KISS!”

With that bold announcement to a frenetic crowd, road manager J.R. Smalling uttered the first words on what would arguably become the greatest live (or at least kinda live) rock-and-roll album of all time.

The band members, all born-and-bred New Yorkers, felt out of sorts in the sunny, palm-treed environs, though that didn’t stop them from indulging in the attendant decadent lifestyle, even on a salary of just $85 per week.

When the smoke coughed up by the fog machine and the pyro cleared, KISS were a bona fide concert sensation, but Casablanca was clearly in trouble. Neil Bogart split from Warner Bros. in September 1974 to go independent, but he was still spending money as if it belonged to someone else. He had also made a massive miscalculation by releasing, in November, a two-LP collection of bits from Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show, expecting that a chunk of the host’s fourteen-million-strong audience would want a purely audio iteration of his televisual bits. It didn’t.

Bogart also wasn’t paying Aucoin and the band agreed-upon royalties, leaving the manager to entertain offers from other labels, including Atlantic. It didn’t help that Aucoin’s partner, Joyce Biawitz, and Bogart had coupled up, adding a conflict of interest to the already tempestuous mix. Biawitz eventually quit Aucoin to work at Casablanca, and in May 1975 the band re-upped with the label.

Despite KISS’s records not selling all that well, Bogart kept pressure on the band to keep churning out albums at a furious pace in order to provide the company with cash flow. Aucoin decided to do a live album next because it was cheaper to record and would showcase the band out in the wild, where they did their best work. He hastily arranged a tour, financing it with $300,000 in credit card debt when Casablanca held up their payments, and hired Eddie Kramer to record the band at shows in four cities: Detroit; Cleveland; Davenport, Iowa; and Wildwood, New Jersey. When Kramer played the tapes, with all the mistakes and deficiencies clearly audible, he had the band do some extensive sweetening, not an unusual practice, inside Electric Lady. Still, Alive! stands as the essential—or at least quintessential—you-are-there document of ’70s hard rock, a double album that presents the band as they were meant to be heard, amid explosions and screams, an idea not lost on the guys creating the music. “Somehow,” Simmons observed, “taking the audience away from our songs makes it a lot more clinical or colder.”

Radio agreed. “Rock and Roll All Nite,” as electrifying a dirtbag cri de coeur as has ever been written, peaked at No. 12, while Alive! itself made it to the Top 10, going gold (that is, shipping 500,000 copies) within three months and eventually selling more than nine million copies, becoming KISS’s biggest album. Alive! also offers the first professionally recorded evidence of Stanley’s between-song kaffeeklatsching with the crowd, a predilection that would reach its zenith with the infamous bootleg collection People, Let Me Get This Off My Chest, which hilariously strings together more than an hour’s worth of his inane spiels. The album’s hint of spuriousness extended to Alive!’s cover photo, which was staged at Michigan Palace, where the band rehearsed. But questions of authenticity became moot for a band that desperately needed to bring their concert experience to their fans’ homes and cars. And Alive! Was an album that would go on to inspire some of the most important purveyors of heavy music.

“I first heard ‘Rock and Roll All Nite’ on the car radio and was blown away,” says Anthrax guitarist Scott Ian of the album’s first and only single. “The deejay never back-announced it, so I had no idea who was singing it. I was singing along by the end. I saw them on television not long after that: Here’s KISS with their hit single ‘Rock and Roll All Nite’! The skies parted, the sea parted, and a lightning bolt hit me. That was it. I was hooked.”

As a kid in Canada, Sebastian Bach, who would join Skid Row in 1987, was a fan of Marvel Comics before he got into KISS, and didn’t even know what the band looked like when he bought a 1975 compilation album called Convoy: 20 of Today’s Hits that featured “Rock & Roll All Night” [sic], a song that he immediately fell for. “But this was one of those fake K-tel-style records that didn’t even list the names of the bands,” he says, unaware that the song was actually a cover by something called the C.B. Radio Music Ensemble. When a friend showed him pictures of KISS, with Simmons vomiting blood, Bach was thoroughly disgusted. “I said to my friend, ‘How could you listen to that?’ Then one day after school my buddy dropped the needle and it was ‘Rock and Roll All Nite.’ I was like, ‘You’ve got to be fucking kidding me! These are the guys?’” Bach would soon be buying KISS records sound unheard. “I don’t judge them: Oh, they’ve got to top that last record. I look at it, like, This person is going to be dead one day, and I want as much art from them as they can possibly give me.”

Alive! Was an album that would go on to inspire some of the most important purveyors of heavy music.

When Kim Thayil first heard “Rock and Roll All Nite” on the radio in Chicago, he had no idea what KISS looked like either. It sounded to him like Bachman-Turner Overdrive, the anthemic Canadians whose “Takin’ Care of Business” and “You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet” ruled rock radio in 1974. But when the deejay announced the band, he thought there had to be some mistake. KISS? That name had to belong to an R&B band or some girl group, right?

He grew even more confused when he found a copy of Alive! at a local shop and glared at the cover. He was expecting to see some open-collared beardos along the lines of the Average White Band. Who and what were these creatures? They didn’t look at all like any rock band he’d ever encountered, except maybe Alice Cooper. He flipped the cover over and investigated the song titles. “‘Strutter,’ the word, looked cool,” he says, “though I wasn’t sure what it referenced.” Then he noticed a song about booze: “Cold Gin.” He thought they must be oriented toward more adult themes, which appealed to this suburban fifteen-year-old like the sweetest forbidden fruit. But then he saw “Parasite” and “Hotter Than Hell,” titles more in line with the glam-and-horror bent of Fin Costello’s jacket photo. He needed to hear more.

After a few weeks of skipping school lunch, he had saved up enough money to do just that. He walked into the record store in the Park Forest Plaza shopping center and buttonholed a clerk named Tom Zutaut, whom he knew from high school. “If I liked ‘Rock and Roll All Nite,’ which I do, will I like these other songs?” Thayil asked. “The titles look like they might be rocking.”

“Yeah, it’s pretty consistent,” Zutaut responded. That was good enough for Thayil. (Zutaut would later put his perceptive ear to extraordinary use as an A&R executive, signing Mötley Crüe and Guns N’ Roses to major-label deals.) “This was an important question because if you liked a song you heard on the radio, it might have been the only good thing on that album,” Thayil explains. “You’d have an album built around the Top 40 hit, maybe two Top 40 hits, and then everything else was filler.”

But that wasn’t the case with Alive! and KISS immediately became his favorite band. “They were the heaviest thing in my or my friends’ record collections,” he says. “It was going beyond the Beatles or Elton John or Bachman-Turner Overdrive.” To catch up on the KISS studio albums he had missed, Thayil signed up for the Columbia Record & Tape Club, a mail-order service that offered discounted introductory packages—say, eleven records or tapes for a penny, provided you agreed to buy as few as eight more selections at regular prices in the coming three years. “I was able to take a risk on bands I had read about or heard of on FM radio. I also got Toys in the Attic, Ted Nugent, Jethro Tull—and some crappy records I ended up selling to a used record store to get money for cigarettes or gas.”

Thayil, who in 1984 would start Soundgarden in Seattle with Chris Cornell and Hiro Yamamoto, hadn’t picked up a guitar yet, but was inspired by KISS’s look, if not their musicianship, to do just that. “Paul Stanley was pretty cool,” he says, “the guitar hanging there, strapped low.” The difficult aspect of his fanaticism was trying to legitimize KISS to disbelieving friends, a rite of passage that has been endured by nearly every admirer of the band. Thayil recalls buying a KISS songbook and learning that “Nothin’ to Lose” was in 7/4. He’d grab a buddy and say, “Seven-four, man! Check it out!” Some of his friends would concede that 7/4 was a difficult time signature to play. “But,” Thayil avers, “nobody was having any of it. They thought it didn’t compare to Zeppelin, and they were right. It took me a while to understand that. I don’t think anyone appraised KISS as musicians in any regard. At best, they were underrated. I mean, they were playing their instruments while wearing high heels, with their legs spread and the guitars at the weird angle.” Thayil and his band would later pay homage to KISS (sort of) with the jokey screamfest “Sub Pop Rock City.”

With the success of Alive!, Bill Aucoin moved his company to a tony office tower at 645 Madison Avenue, staffed up, and created a space—filled with mirrors, chrome, and flowers—that reflected his refined taste and the seriousness with which he took his business. A gilded palace where he could begin to build an empire.

__________________________________

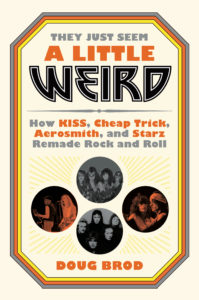

From They Just Seem a Little Weird: How KISS, Cheap Trick, Aerosmith, and Starz Remade Rock and Roll by Doug Brod. Used with the permission of Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc. Copyright © 2020 by Doug Brod.

Doug Brod

Doug Brod is the former editor in chief of SPIN magazine and was a long-time editor at Entertainment Weekly. He has worked for Atlantic Records, taught at New York University, and was a segment producer of the comedy/music television series Oddville, MTV. Brod has also written for the New York Times, Billboard, Classic Rock, The Hollywood Reporter, and The Trouser Press Record Guide. A native New Yorker, he lives with his family in Toronto.