How James Thomas “Cool Papa” Bell Became a Negro League Superstar

Lonnie Wheeler Celebrates One of the Fastest Men Ever to Play Baseball

For their own survival, the Negro Leagues had become a system of stars. Of course, even the brightest of them were of only casual interest to the metropolitan dailies, which still hadn’t settled on “Satchel” or “Satchell” or “Paige” or “Page.” Needless to say, the headlines were reserved for the leading lights of the designated major leagues, where, in 1934, pillar-of-strength Lou Gehrig was claiming the Triple Crown in the American League and piece-of-work pitcher Dizzy Dean—the white Satchel Paige, if you will—was winning hearts and 30 games, the latter of which no National Leaguer has done since.

Satchel himself won 20 that year on behalf of the Pittsburgh Crawfords—he was the whole package now—but wasn’t compelled to answer their every call. In August, for example, he was off to Colorado for the annual Denver Post national tournament, rocking a fake red beard and blazing 23 straight scoreless innings for the House of David, which won the title in a thrilling match against the Kansas City Monarchs. Pitching to his familiar Negro League battery mate, Bill Perkins (“Thou shalt not steal” was emblazoned on Perkins’s chest protector), Paige carried the House of David into the championship game with a 2–1 semifinal victory over Chet Brewer and the Monarchs, the first entirely black team in the tournament’s history.

For the Crawfords, engaged in a pennant race, Paige’s two-timing illustrated what can happen when a franchise permits itself to be held hostage by its marquee attraction. For the Negro National League, the scenario, like the season, was another function of an untidy alliance in which teams were merely vehicles, schedules were simply outlines, and championships figured in there somewhere, somehow, sometimes.

The star system was not Cool Papa’s thing, necessarily, although he fit the bill manifestly. His baserunning was ballyhooed in virtually every town he visited; he had a continuing habit of playing for the winning side; as an outfielder he “nabbed everything hit in his direction, and kept base runners honest with his accurate throws,” according to William McNeil, author of The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League; and in the spring of 1934 he was coming off winter league titles in batting average and stolen bases. (In Los Angeles he’d played next to Stearnes and Wild Bill Wright, the three of them constituting what, in McNeil’s estimation, “may have been the greatest outfield in the annals of baseball.”)

Bell was the same player he’d been in St. Louis, but he was more secure in his station and dusted now with Crawford glitter. In Pittsburgh, Gus Greenlee’s team was followed on both the sports and society pages, and there was plenty to write about. The entertainment for Paige’s wedding at the Crawford Grill was provided by his best man, Mr. Bojangles Bill Robinson. At Greenlee Field, a nattily dressed patron might find himself sitting next to Joe Louis. When the ball game ended, Lena Horne was liable to croon on the grass. After dinner at the club, Duke Ellington just might strike up the band.

Meanwhile, at .364 (the best of his reported batting averages) or whatever it might have actually been, Cool Papa would significantly outhit Oscar Charleston, Josh Gibson, and Judy Johnson, the other three Hall of Famers in the Crawfords’ lineup (when Paige wasn’t pitching) for 1934. When William Nunn of the Pittsburgh Courier discussed the apparent inevitability that black players would soon integrate the major leagues—a movement championed by Heywood Broun and Jimmy Powers of the New York Daily News—he put the Pittsburgh center fielder on the short list of likely candidates.

Cool Papa’s stardom was not design but residue, a natural by-product of his speed and grace.

“The phantom wall of race prejudice,” wrote Nunn, “which for years has kept Negro players out of big-time diamond competition, is under a bombardment from which it cannot hope to stand…And now, look at the cream of the crop…men of the type of Willie Wells, whom westerners referred to as the ‘Colored Hans Wagner’; Dick Lundy, one of the admittedly great shortstops; ‘Cool Papa’ James Bell, who can trail a ball farther than any man in baseball.”

Those were words that resonated with Bell. Integration, rather than adoration, was the shape that his ambition assumed. The gentleman from Mississippi had played too successfully, against too many white opponents, to settle for less. He was interested, also, in the comparative windfall that his talents would rightly command if he wore a major-league uniform, increasing his salary by a multiple of five to ten—there was, after all, Clara Belle to support, the monthly contribution to send his mother, a certain vesture to maintain, and, most of all, the pursuit of justness—but such considerations as celebrity and station were lower priorities. Cool Papa’s stardom was not design but residue, a natural by-product of his speed and grace.

“When Cool and I played together in Pittsburgh, he was the most popular player on the team both among his teammates and the fans,” Judy Johnson recalled to James Bankes in The Pittsburgh Crawfords. “All you had to do was walk down the street with him and you knew why. He was a beautiful dresser. Absolutely immaculate. He had perfect manners and you never heard him say even a hell or a damn. He had time for everybody. Signed autographs, talked to people, gave advice on baseball, anything they wanted. All the time showin’ his big beautiful smile.”

The front office, however, had a different perspective on Cool Papa’s popularity. He was a bargain at $220 a month, and any heightening of his stature—any renown or publicity that might escalate his price—was a threat to that economy. For Bell, the harsh reality hit home on a road trip early in 1934 when his torrid batting began to overtake Josh Gibson’s and he was instructed not to send back any out-of-town newspaper clippings in which his exploits were featured.

The Crawfords had decided that their rainmakers were Gibson, who was local as well as Olympian—his showstopping home runs could actually be measured—and of course Paige, the lanky force of nature to whom the game was equal parts sport and theater. The club’s traveling secretary, wishing only to spread the word about good baseball being played, was fined for stating his intention to dispense unspun information about who on the club was doing what. “The self-effacing Bell,” wrote Bankes, “as sweet a human being as was ever elected into the Hall of Fame, found himself in the shadows, both in fame and finances, of the two glamorous stars.”

Cool Papa was kindly disposed toward the pair at the top of the bill and would begrudge neither his glory. He was not so forgiving, though, concerning the Crawfords’ calculated denial of his own contributions. Wise to suppression from Southern custom and mainstream baseball, he hadn’t counted on more from his own team.

“When I went to the Crawfords,” Bell said to John Holway in Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues, “they had Charleston, Gibson, Paige. They weren’t going to build anyone over them. They never did advertise you over those guys. The Crawfords advertised Satchel. They just kept dramatizing and dramatizing him, but we had guys who would win more games than him. Now, when we played in California, they would bill Satchel, and he would get 15 percent. When they billed me, they had those wagons all going around saying, ‘Bell’s going to be here tonight.’ But I didn’t ask for anything. I only got a cut like the rest of the ballplayers got. I’m not the guy wants to be praised too much. I never wanted to be a big shot.”

Even so, there he was again at the festive East-West affair in late August, leading off for the East and coming to the plate in the eighth inning of a scoreless duel. He’d played a part in the scorelessness, having hit his relay man, Dick Lundy, with a throw from deep center field, whereupon Lundy pegged out a runner at home plate. But the run prevention accrued mostly to the dazzling pitchers.

The starters were Cool’s old teammate, Ted Trent, for the West, and a 21-year-old rookie sensation named Slim Jones, a long left-hander who’d been turning heads all season for the Philadelphia Stars. For the East side, Jones was followed by Tin Can Kincannon and then Paige, who’d known better than to spurn the all-star invitation a second time. Big Florida’s successors were Chet Brewer and now Willie Foster, who made the mistake of walking the fastest man in the sport to start the eighth.

Integration, rather than adoration, was the shape that his ambition assumed.

Bell, as expected, stole second base, and he was still there with two outs when Boojum Wilson broke his bat on a flare to short center, which Willie Wells retrieved from his shortstop position but not in time to keep Cool Papa from scoring the only run of the game. Satchel did the rest, with no sign of his hesitation pitch but liberal use of the double windup.

Paige and Bell would reunite later that year on a talented team put together by Tom Wilson for the California Winter League. Luminaries trailing Cool in the Elite Giants’ lineup included Wells, Stearnes, Suttles, Wild Bill Wright, catcher Larry Brown, third baseman Felton “Drifty” Snow, and second baseman Sammy T. Hughes. Paige was joined on the pitching staff by able starters Pullman Porter and Cannonball Willis.

The CWL’s inclusive posture was reflected by supportive Californians and the Los Angeles press, which took the maverick attitude that good baseball is good baseball. The winter season opened with a parade long enough that three bands could play simultaneously, and the Los Angeles Times described the Elite Giants as “a colored baseball club which is so good it ain’t nothin’ else but… ”

The Giants were so good, in fact, that five of them—Paige, Bell, Wells, Stearnes, and Suttles, in chronological order—would end up in the Hall of Fame. At the time, of course, that was a preposterous notion. For one thing, Cooperstown’s maiden class wouldn’t be announced for more than a year. And it would be 37 before Paige became the Hall’s first black member.

Immortality, however, visited two of those five well ahead of schedule. It happened after the mischievous Paige began telling folks about the mind-boggling speed of his outfielder friend. Satchel’s words may have deviated from time to time, and decades of approximated accounts, oral and published, have assumed various forms, but the basics were always the same.

“Cool Papa Bell,” he said, “is so fast that, when he goes to bed, he can turn out the light and be under the covers before it’s dark.”

The famous line almost certainly derives from the 1934–35 Winter League season. The likeliest version of its origin was offered by Bell at a 1981 Negro League reunion in Ashland, Kentucky, then printed the following year in St. Louis Magazine. It begins with him alone in their California sleeping quarters.

“One night,” recalled Cool Papa, “before he got back, I turned out the light, but it didn’t go off right away. There was a delay of about three seconds between the time I flipped the switch and the time the light went out. Musta been a short or somethin’. I thought to myself, here’s a chance to turn the tables on ol’ Satch. He was always playin’ tricks on everybody else, you know. Anyway, when he came back to the room, I said, ‘Hey, Satch, I’m pretty fast, right?’

“‘You’re the fastest,’ he said.

“‘Well, you ain’t seen nothing yet,’ I told him. ‘Why, I’m so fast I can turn out the light and be in bed before the room gets dark.’

“‘Sure, Cool. Sure you can,’ he said.

“I told him to just sit down and watch. I turned off the light, jumped in bed and pulled the covers up to my chin. Then the light went out.

“It was the only time I ever saw Satchel speechless. Anyway, he’s been tellin’ the truth all these years.”

Perhaps not the whole truth, however. The episode may well have been predicated on the fluorescent lights that back then were found in some hotel rooms and boardinghouses, the kind that illuminate methodically, one end at a time. It may also have involved wagering.

One iteration of the story has Cool winning ten dollars from Paige on the initial gambit. And if that was the case, another twist seems highly plausible: that the enterprising roomies turned the trick a number of times for skeptical teammates willing to put a few dollars behind their doubts.

__________________________________

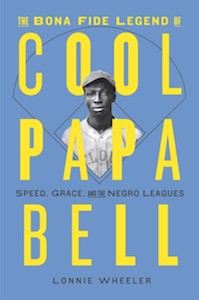

Adapted from The Bona Fide Legend of Cool Papa Bell: Speed, Grace, and the Negro Leagues. Used with the permission of the publisher, Abrams Press, an imprint of ABRAMS. Copyright © 2020 Lonnie Wheeler.

Lonnie Wheeler

Lonnie Wheeler (1952-2020) was the author or co-author of many books on baseball including I Had a Hammer with Hank Aaron, Pitch by Pitch with Bob Gibson, Sixty Feet, Six Inches, with Bob Gibson and Reggie Jackson, Long Shot with Mike Piazza, Bleachers: A Summer in Wrigley Field, and Intangiball, winner of a 2016 SABR Baseball Research Award.