How Jackie Robinson Paved the Way for the Undersung

Larry Doby

Luke Epplin on the Impact of a Sports Pioneer and the

Black Players Who Followed

In his autobiography, I Never Had It Made, Jackie Robinson wrote that in the weeks after he broke the major-league color line in April 1947, he often felt like “a black Don Quixote tilting at a lot of white windmills.” The abuse nearly broke him. Bench jockeys demanded he go back to the cotton fields, the jungle, the bushes. Some hotels refused to accommodate him. Letters poured in with theats to him and his family. Players on the St. Louis Cardinals allegedly plotted to walk out of their first game against the Brooklyn Dodgers.

When he first signed Robinson, Branch Rickey had laid out a series of directives for the rookie to follow. Most important, Robinson was to hold his temper at all times, absorbing the blows without lashing out or fighting back. Pioneers like Robinson, sportswriter A.S. “Doc” Young later asserted, “had to walk a straight path, narrower than for any previous performer, and live as straight-laced as religious servants dressed in the cloth.”

His teammates, a few of whom had circulated a petition in spring training calling for his removal, were wary and distant at first. “In the clubhouse Robinson is a stranger,” journalist Jimmy Cannon wrote in mid-May. “The Dodgers are polite and courteous with him but it is obvious he is isolated by those with whom he plays… He is the loneliest man I have ever seen in sports.”

It didn’t help that Robinson opened the season in a slump. But as the weather warmed, so did his bat. He raised his average by 40 points in May, then by 50 in June. The kinetic and gutsy play that had won hearts in Montreal came into view. Spurred on by Robinson, the Dodgers surged to the top of the National League standings in late June and never relinquished the lead. Everywhere he’d played—the minors, spring training, and now the majors—he’d excelled, which helped convince certain skeptical fans and teammates that Robinson had earned his spot in the league.

On May 4th, as Robinson was fighting for his place in Brooklyn, the Newark Eagles opened their 1947 season against the New York Black Yankees in Stamford, Connecticut. On that cold, drizzly Saturday afternoon, the team picked up where it had left off. While Monte Irvin and Lennie Pearson clubbed two homers apiece, it was Larry Doby who stole the show. Setting a single-game Negro National League record, he lofted three balls beyond the outfield fence at Mitchell Field. The Eagles ran away with a 24-0 victory.

Twenty-three years old and fresh from a winter stint in Puerto Rico during which he’d batted .358 with 14 home runs, Doby stood poised for a breakout summer. In the Eagles’ first eight games he smashed seven home runs. His batting average was a preposterous .517. The Eagles, in turn, romped through the season’s first month with what Effa Manley deemed “a vigor that fairly oozed confidence.”

The threat of fans shifting their allegiance from the Eagles to an integrated major-league team nearby didn’t deter the Manleys from pouring money into their club. In the off-season, they’d upgraded the team’s rickety bus with a sleek Stratoliner, across whose sides was painted “Negro World Champions.” Air-conditioned and roomy, the bus had set the Manleys back $15,000, which Effa Manley brushed off.

“The personal health and comfort of my boys are my chief concern and I will leave no stone unturned in order to keep them happy,” she told the New York Amsterdam News.

While attendance at Eagles games in Newark’s Ruppert Stadium started out strong in 1947, it leveled off gradually as Jackie Robinson more and more commanded the attention of Black fans. As during the previous season, Dodgers scouts remained steadfast presences in the stands. Their interest in Doby, already strong, intensified as the temperature ticked up.

Soon, they had company.

On May 27th, Bill Veeck placed a midnight call to Lou Boudreau. The Cleveland Indians had just lost to the Tigers in Detroit, dropping them to fourth place in the American League with a 13-13 record. The 1947 season, not yet a quarter completed, was already slipping away.

Both men knew what was missing. Boudreau begged his boss for a hard-hitting outfielder; Veeck reportedly told him he was willing to “separate the club coffers from a very large bundle of currency to obtain the same.” But being willing to spend wasn’t all it took. If Veeck hadn’t been able to land a premium outfielder during the winter, what chance did he have of doing so now, weeks before the major-league trading deadline?

Unbeknownst to Boudreau, Veeck wasn’t looking only at the trade market. At some point in the off-season, he’d reached out to Ray Dandridge, a former third baseman for the Newark Eagles who now was burning up the Mexican League. But Dandridge, according to Veeck biographer Paul Dickson, was reluctant to sacrifice his stability and five-figure salary for the uncertainty of the Indians’ offer.

Veeck also reached out to Abe Saperstein along with a handful of Black sportswriters, Cleveland Jackson and Wendell Smith among them, for advice and guidance about which players in the Negro Leagues had the best long-term potential. Like Rickey, Veeck hoped to desegregate his club with young players who had experience enough to handle the burdens of being racial pioneers but whose best seasons were still on the horizon.

Their search soon narrowed to Larry Doby. He seemed to possess everything that major-league executives were searching for in a Negro League player. He was a married war veteran who’d competed on integrated teams in high school and college and he was demolishing Negro League pitching like no one else. The scouting report that Bill Killefer filed on Doby affirmed the choice: “[Doby] can play in this league… I don’t know whether he belongs in the infield or the outfield, but he can play.”

Brooklyn Dodgers scouts were slightly cooler on Doby. One argued that he “is a fine prospect but he hasn’t learned where the strike zone is. He’s two years away from the majors.” Clyde Sukeforth, who’d scouted Doby the previous summer, would assert that there “are many excellent athletes in the Negro loops and Doby was one of the very best but the jump immediately to the majors is too great—almost unfair to the players themselves.” Instead, as they’d done with Jackie Robinson, the Dodgers preferred to ship their signees to the minors to fine-tune their fundamentals and help them acclimate to all-white dugouts.

Veeck favored a different tactic. “I’m not going to sign a Negro player and then send him to a farm club,” he asserted to The Pittsburgh Courier. “I’m going to get one I think can play with Cleveland without having to go to the minors first. And, when I do find him he’s going to join the club right away.”

Part of his rationale was practical. With the top clubs in the Indians’ farm system spread through the South and in Baltimore, a city notoriously hostile to Black players, his options were limited. Veeck also believed that Jackie Robinson’s protracted entry into the majors and the 18-month media storm it’d fomented had put “too much pressure” on him. More than anything, Veeck desired a pennant as soon as possible, and his vision for rapid-fire integration was wholly in keeping with his go-for-broke, whatever-works approach to achieving it.

If another joined them—especially one in the American League—integration would inch closer to being an irreversible reality.

“One afternoon when the team trots on the field,” Veeck predicted, “a Negro player will be out there with them.”

One night in June 1947, Roy Campanella rang Larry Doby. Since the season before, when he’d been the starting catcher for the Dodgers’ Class-B farm club in Nashua, New Hampshire, Campanella had moved up to the Triple-A Montreal Royals. He was a step away from the major leagues, the lone Black player who could say as much—but not, he sensed, for long. Somewhere along the line, Campanella had caught wind that the Dodgers planned to sign Doby and send him to Montreal for seasoning. Over the phone, he told Doby that they could expect to become Royals teammates imminently.

Before they put forth an offer, however, Dodgers officials learned of the Indians’ interest in Doby. For the first time, two major-league clubs were jockeying for the same player in the Negro Leagues. Rather than swooping in before the Indians could act, Branch Rickey backed off. He seemed to understand that as long as the Dodgers were the only major-league franchise that had crossed the color line, integration would remain precarious. But if another joined them—especially one in the American League—integration would inch closer to being an irreversible reality.

As Rickey told Wendell Smith, “It certainly would be good if some other club signed a Negro player. It would help us a lot. You know, there are a lot of people in baseball who haven’t gotten over the fact that we went ahead and put Robinson on our club. If someone else signs a Negro player, we’ll at least have someone on our side.”

*

Late in June, Louis Jones, the Indians’ assistant director of public relations, paid Doby an unexpected visit in Paterson, New Jersey. The two, who had never met before, attended a Yankees game against the Indians in New York City on the 25th. Frank “Spec” Shea, a right-handed rookie, was pitching for the Yankees. Jones likely didn’t know that Doby had rapped a double off Shea months earlier in Puerto Rico, where his winter team, the San Juan Senadores, had played an exhibition series against the Yankees. So when Jones asked Doby if he could play the kind of baseball they were watching, Doby didn’t hesitate in responding: “There’s nothing down there I can’t do.”

The following evening Jones traveled to Trenton to watch the Eagles clash with the Baltimore Elite Giants, a surging divisional rival. The Eagles racked up five quick runs in the first but then squandered their momentum and, eventually, the lead. Doby tallied three hits in the losing effort, which was presumably enough to satisfy Jones.

Before leaving, Jones pulled Doby aside and let him know that he’d likely be back in a week or so. There was reason for Doby to be skeptical. Ever since Jackie Robinson had signed with the Dodgers in late 1945, rumors had flown about numerous other Negro League players being on the verge of signing with this or that major-league organization, none of which had come to pass.

Jones, however, kept his word.

__________________________________

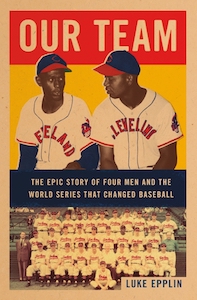

Excerpted from Our Team: The Epic Story of Four Men and the World Series That Changed Baseball. Used with the permission of the publisher, Flatiron Books, a division of Macmillan Publishers. Copyright © 2021 by Luke Epplin. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Luke Epplin

Luke Epplin’s writing has appeared online in The Atlantic, The New Yorker, GQ, Slate, Salon, The Daily Beast, and The Paris Review Daily. Born and raised in rural Illinois, Luke now lives in New York City.