How I Turned My Discarded Novel Drafts Into an AI

Could a Computer Learn to Imitate Me?

The other day, I read through feedback on my novel-in-progress from my writer friend Ethel Rohan, who concluded her comments with the line: “Ending feels rushed, and I’m not clear on Gaston’s story/character arc/resolution.” The comment was noted with track changes and tied to the final paragraph of the novel. As I looked up from the screen, I realized that though I had constructed several hundred pages of text, I had completely failed to convey meaning.

I hadn’t known this, of course. When I gave my friend the draft, I’d fancied it close to finished, close enough that I even mentioned its existence to my agent, saying I hoped to get it to her soon. This excitement was in many ways a hallucination. Whatever story I had tried to tell was only apparent to me. The fabric of my text had felt soft and luxurious beneath my fingers, but more like cellophane or glass to another person, who stared through it, perhaps at his own to-do list or sink-load of dishes, wondering what the hell he was supposed to be looking at.

How we construct and convey meaning is a question I’ve dedicated many hours to considering, often through trial and error. I have hundreds of pages of failures that I keep on my hard drive which often make me question my own sanity when I choose to try again. And I’ve made an informal study of how other writers approach this work. The Paris Review’s “Art of” series is a great resource. I save the lines that strike me:

“In ‘The Waste Land,’ I wasn’t even bothering whether I understood what I was saying,” T.S. Eliot

“The craft or art of writing is the clumsy attempt to find symbols for the wordlessness.” John Steinbeck

“It’s hostile in that you’re trying to make somebody see something the way you see it, trying to impose your idea, your picture. It’s hostile to try to wrench around someone else’s mind that way.” Joan Didion

The lines that strike me are varied, but they usually concern the process of formulating an idea and then conveying it, of translating the vague and shifting impulses of thought into a physical text that another person can read and feel moved by. I imagine it as a pattern: an intriguing structure born in the head but described in such a way that another person can, from the instructions contained within a single book, construct a similar structure and feel equally enchanted.

I suppose it should come as no surprise that we discover patterns in literature, in the books we choose for ourselves (a specific genre or favorite author, for example) as well as the books our society finds popular. We have lists of best sellers that reflect our communal preferences, and now we even have algorithms that have noted commonalities between our best selling texts—from themes that have consistently proved popular, to story elements such as setting (cities are great!) that an AI can identify and use to predict whether a new book will be a run-away hit, or not. The Bestseller Code by Jodie Archer and Matthew L. Jockers describes this kind of work:

In the end, we winnowed 20,000 features down to about 2,800 that were useful in differentiating between stories that everyone seems to want to read and those novels that were more likely to remain, well, niche.

How do I feel about that? I find this type of study fascinating as well as demoralizing. That we can create an algorithm that predicts a book’s marketability makes the industry feel small to me, and less romantic. The individual vision becomes a text file that can be read, evaluated, and quantified by a computer program.

But the connection between the world of fiction and artificial intelligence does not stop with the bestseller algorithm. The Washington Post ran a story about poets and novelists hired to make AI conversation “feel natural.” Several years ago, novelist Neal Stephenson was hired by a virtual reality startup. And researchers, including a team at Google, used a database of unpublished romance novels to “help Google understand and produce a broader, more nuanced range of text for any given task.” In the first two cases, writers were hired for their contributions; in the latter, writers’ work was studied only by a computer, which read the work and identified patterns, and the writers only learned of this after the fact.

That a large technology company has used and benefited from the thousands of hours a writer invested in realizing a novel is probably a surprising outcome for an writer whose goal is traditional publication. Her art and the lure of sharing meaning with an audience becomes merely training data for an artificial intelligence to profit from. I must admit, however, that when I read the Guardian story about the romance writers and Google, my first thought was not anger, but revelation. Good god, I thought. I’m sitting on a treasure trove of unpublished material: novels, short stories, and dozens of drafts for each because I save them all. Could I make an AI and finally use this work? Could I make something meaningful from the collection of documents by collaborating with technology instead of being irritated by it?

The idea that art can emerge from a large amorphous body of work is not new. A famous example belongs to William S. Burroughs, whose “word hoard,” approximately 1,000 pages of text, became the basis for several highly regarded books, including Naked Lunch. My word hoard would have a somewhat different nature—dozens of drafts of different projects combined instead of pulled apart—but I figured what the hell, I’d do it.

I stumbled upon a group of people who were interested in the task of computer-generated storytelling, who had in fact created a special event around it: NaNoGenMo (National Novel Generation Month). NaNoGenMo is much like the more widely known NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month, in which people commit to completing a 50,000-word novel over the course of a month), only instead of writing a novel, participants commit to “writing computer programs that will write their texts for them.”

As I considered the ways people were using technology to generate story—often using an initial list of words and instructions—I was reminded again of how differently individual writers approach their craft. Some human writers who employ elaborate constraints began to seem eerily like an AI to me:

“For several years, each time that I prepare to write a book, I first arrange the vocabulary I am going to employ. Thus, for L’Homme foudroyé, I had a list of three thousand words arranged in advance, and I used all of them”

I thought of Anne Carson’s “A Fragment of Ibykos Translated Six Ways,” which relies on constrained and very different vocabularies (“pp. 17-18 of The Owner’s Manual of my new Emerson 1000W microwave oven” or “p. 47 of Endgame by Samuel Beckett,” for example) to convey meaning in the context of a single structure, a translated poem. Not until I began this project did I begin to think of my own vocabulary as a constraint in my work, a part of my process, and a quality that defines me. I took a closer look at the words I use most often and found other words that I never use at all (revile, for example). I surprised myself when I discovered that I used the word “suck” more than “creating” in my work.

I did some additional word counts to see what I’d discover about myself:

genius: 18

idiot: 50

art: 2218

money: 231

stop: 371

go: 4133

sorrow: 17

joy: 137

friend: 535

enemy: 12

Looking at my list, I thought about the first international beauty contest judged by an algorithm where out “of 44 winners, nearly all were white, a handful were Asian, and only one had dark skin. That’s despite the fact that, although the majority of contestants were white, many people of color submitted photos, including large groups from India and Africa.” I thought about the analogies an AI came up with based on “a corpus of three million words taken from Google News texts:” Father is to doctor as mother is to [nurse]. Pointing out that there is a bias in artificial intelligence—or that the bias seems to reflect and magnify ones in the underlying culture—is hardly new, but it bears repeating. I had no idea what unconscious biases I might find when I used my own work. I shuddered to think.

The technology I chose for generating a story was called the neural-storyteller. The code would essentially allow me to take my body of text and use it to train a model to generate descriptions of whatever images I fed to the program. The example implementation used two different corpuses: the work of the romance writers (so popular!) and Taylor Swift lyrics. The output is often very funny (see it here). The sample neural-storyteller stories told one-picture stories. My idea was to feed the software a series of images that together told a story. My pictures would serve much like a storyboard would serve a movie director, providing a visual outline of a story. I would keep the story itself very simple, just five or six frames, because collaborating with a computer gets expensive very quickly (I had to rent time on cloud servers to do this work).

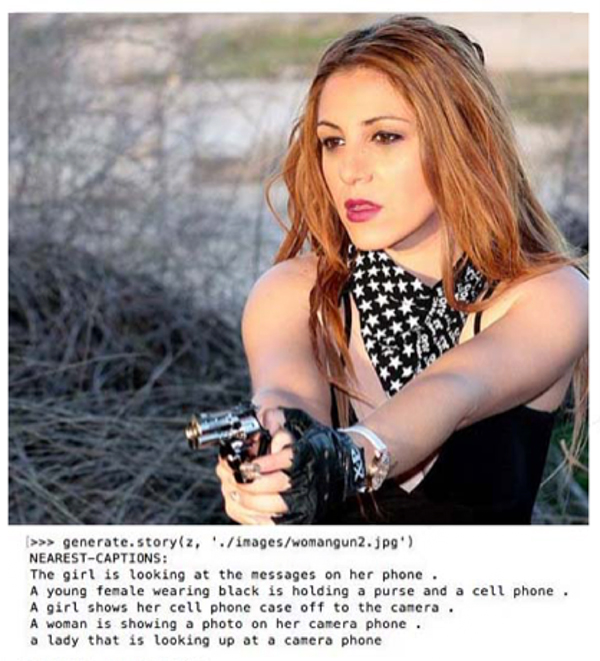

For my first attempt, I decided to try a crime scene. I planned to tell the story twice, switching the gender of the characters, and I collected a number of photos with men and women and guns. But the idea failed because the AI kept seeing cellphones.

That’s right. Instead of guns, my criminals were wielding cellphones! My inquiry into why this was turned into an action-packed adventure that became the subject of another essay. Suffice it to say that I did not fully understand how my model arrived at what it did, but I was fascinated by what it came up with. What exactly did it see? Here’s text the AI generated based on what it understood of the image of me:

“Only a man was standing in the forest, and he used to give her words, fearing the appearance of a tree so long ago.”

I marveled at the “Truth” (the original sentence) and “Sample” (model-generated) lines my model spat out as I was training it. I thought of these samples as my AI reconstructing, as best as it could, the sentence it was given. In other words, each sample line was an example of my AI trying to be me!

Truth: The morning sun does not clarify it.

Sample: The day does not read it properly

Truth: It is a code.

Sample: It is a mess.

The samples were great for short sentences, but the longer the sentence, the worse my AI did. I failed to get a result I liked. I needed to learn more, understand the technology better. I tried other models, I learned about loss—the more mistakes the model makes, the higher the loss—and techniques I could use to try to minimize it. I tried out an implementation based on Andrej Karpathy’s Recurrent Neural Network. I was very impressed by the example text his model generated, but disappointed when I compared the texts that the “best” and “worst” of my own models output.

Best (from the model with the lowest loss) ” And I should work so much , that should I see if she was headed into a faceless stretch daylight .”

Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge

Worst (from the model with the highest loss): “” The devil ‘ s a prophet ! It ‘ s nice .”

Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge

I was hard-pressed to say which was the stronger of the two. The model had improved in a measurable way, but only the technology could see that clearly.

I wondered what it had learned. To be more like me?

My work on this project continues. I have not yet generated a story I like. Still, each time I train a model and output a result, I wait as I might for the new release from a favorite author. And each time, after hours of training and troubleshooting, the generated text appears on my screen and my AI sits silently, almost as if it were awaiting the answer to the question I ask so often myself: Look, I wrote this, it says to me. I worked very hard on this. What do you make of it? What does it mean, to you?

Kirsten Menger-Anderson

Kirsten Menger-Anderson is a writer and researcher based in San Francisco. She is the author of Doctor Olaf van Schuler's Brain.