How I Tracked Down the Hidden Lives of the Radical, Wealthy Morris Sisters

Julie Klam on How She Told the Story of Her Notable Relatives

In 2008, I published my first book, Please Excuse My Daughter, a memoir about my mother and me and how I grew up, and it dipped a little into my mother’s family’s history, which was rich and interesting. Her mother’s uncle, Sam Golding, developed the neighborhood of Rego Park in Queens during the 1920s. In fact, I had always been told that the name Rego Park was for my mother’s grandmother Rose Golding, but in every documented story about the history of the name, it’s said to come from Real Good Construction Company. When I told that to my mom and Aunt Mattie, they said everyone was wrong, they were certain the family story is true. End of story.

There are buildings and hospitals around New York City that still bear his name. Once at my parents’ house, I found a bag of yarmulkes from various weddings and bar mitzvahs. One was from Sam’s daughter Faith’s wedding to Ronald O. Perelman, the Revlon tycoon who went on to marry Claudia Cohen, Patricia Duff, Ellen Barkin, and Anna Chapman. But his first wedding in 1965 was to my relative. (All of this information was in my book. While I used the internet to research it, it was different then: Google wasn’t a verb yet, and a lot fewer documents were available online.)

I looked through old New York City phone books—actual physical phone books—found people’s addresses, and interviewed the people who were still alive at that time, and though I couldn’t always verify their stories, it was fine. It was a memoir, not a history book, after all. I loved the quest for information about my family, though: It was like searching for buried treasure and actually thinking there was a decent chance I would find it. The feeling I had poring over the names of the 1943 Manhattan phone book and finding my grandfather’s office address and telephone number was like I had time traveled. In 1943, he was alive, and people who wanted to talk to him looked up his telephone number in that phone book and called him at his office. A secretary answered, and eventually they got to my grandpa.

When I finished my memoir, I thought the next logical project would be a book about the Morris sisters. I had written about my mother and her family, and now I had this fascinating piece of my father’s family to investigate. I’d heard about these “manless,” independent, rich sisters who existed in a time when the world did not support any of that. Who were they? How did they do what they did? They were kind of radicals. Did any of what made them tick exist in me? I was trying to be more independent in my marriage, and maybe knowing how they did it would help me. They were celebrities in our family instead of being “famous” in the world like Irving Berlin. I needed to know who these women in my family were.

I started researching them, but it didn’t take me long to realize that for women who were so famous within my family, there didn’t seem to be much written about them in the world. Not to mention the fact that their last name, Morris, was extremely common, and they had lived in New York City, which isn’t exactly Bedford Falls. (This was around the time Ruth Etting’s “A Needle in a Haystack” became my theme song. It stayed in my head for three years.)

I started my research by interviewing first Claire and then her older brother, Bobby. While their stories were helpful, they were only a start. I needed more. To really find, understand, and tell the story of the Morris sisters, I would need to dig deeper than anecdotes, to go beyond the family lore to the places where they had lived and where their family had come from and generally look for things (to use a technical genealogy term). My agent, publisher, and editor were all on board.

There were problems, though. My then husband and I didn’t have much money, and we had a child in kindergarten who needed a lot of attention (as opposed to the self-cleaning, autonomous models). My husband was freelancing, and his jobs required very long days and frequent travel. We couldn’t both be working full days and traveling a lot, so I put aside the idea for a book about the Morris sisters and wrote a book about dog rescue instead, an activity I was doing anyway. (The dogs were on a different side of my family.) As I began to write my second book about dogs, it was evident that my marriage was not going to make it. I went on to write a book about friendship, and while I was writing that book, my husband and I began the lengthy, exhausting process of getting divorced. So it was one step forward (the child got older) and two steps back (I was now a single parent with even less money than before).

During these years, I had been writing a book a year as well as other pieces for magazines. With all that was happening in my life, it was now taking almost three years to write what became my fifth book. It was about the nature of celebrity, which sounded like a good idea because it wasn’t about me: I was at a point in my life where the last subject I wanted to write about was myself. Except I had a really hard time doing it: I became a kind of champion at not writing my book. I would fantasize about having the kind of job you left the house for and sat at a desk and people gave you tasks to complete—much as I did when I worked at the life insurance company. I envied anyone who knew what they were supposed to be doing, and I would grill people about the stresses of their jobs. (It turns out the only jobs with no stress are the ones you aren’t doing.)

They were celebrities in our family instead of being “famous” in the world like Irving Berlin.

Somehow the book got written and published, my divorce was finalized, and I found myself in the magical place of deciding what to write next. It’s such an amazing place to be because you can choose where you want to go for the next two or three years. It’s all possible and every idea in your mind is an instant classic/billion seller. Do I want to write about real-life wizards or haunted houses or spelunking? Well, no. I had several conversations with friends and one with my good friend Ann Leary, who told me about the research she’d been doing on Ancestry and the amazing information she’d learned about her family. Ann is someone who doesn’t do anything halfway, so by the time we talked, she was already an expert in family searches. I told her about my long-abandoned task to write about the Morris sisters. She pointed out that the internet had changed since I first thought about this book and that more and more information was becoming public and available. So she said, “Do it!”

“Maybe,” I said. And then I went to the gym.

While I was there, Ann started texting me all of the details she was discovering about the Morrises on Ancestry.com. She was right: The details were intriguing, and there was much more information about them than Claire and Bobby had told me several years ago.

Sometime on the StairMaster while I was trying to ignore The Price Is Right, a book about the Morris sisters seemed possible, and something that I could get really excited about.

I went home and pulled out the old proposal and found that I had taken a lot of notes and had a small folder of research. It had been ten years—ten really difficult years. Divorce, anxiety, and insomnia, too many glasses of sauvignon blanc. All of this left my brain a little worse for wear, but the good news was that the story of the Morris sisters still felt new to me. I was still fascinated by what I had found and intrigued by the possibilities of what I could find that lay in front of me. It began to feel that I couldn’t not write this book.

When you start researching family, well-meaning people direct you to genealogists. As with most vocations, there are amateurs and professionals, and they are all similarly driven: They are the experts at digging for information about your ancestors and family. This, I have learned, is a double-edged sword.

I have always felt that the copy editors who have worked on my books and magazine pieces have a genetic makeup fundamentally different than mine: Their brains operate on a different wavelength. They notice mistakes and inconsistencies that in a thousand years I never would have found. I have the same feeling about genealogists. They think differently than I do. They keep looking even when they’re not finding anything and it seems that they won’t learn anything new about the people you want information about.

Someone I talked to early on in the research for this book told me that genealogy is just a series of paths that lead to brick walls. “Brick wall,” I learned, is actually a very common term you hear in genealogy. I am not a genealogist. (It’s taken me three years to spell it without looking it up.) I am not a researcher. (I research people and topics the same way my child looks for something he can’t find in his room, sort of a fast scan of a large space and then falling to the floor in defeat.) I came to this conclusion about myself when I spent several hours at the New York Public Library trying to track down information about the Morris sisters and the only useful detail I was able to find that day was the location of the bathroom. And I was so psyched about it.

And although I’ve written for newspapers and magazines, I’m not really a journalist. I don’t like bothering people. If I call a source and the person doesn’t respond right away, I quietly assume the information can’t be found.

I straddle two mindsets. I grew up without the internet, so when I was young if I wanted to find something, I went to the library. If I wanted to find a word within a document, I read the whole document as carefully as I could looking for the word. It was a slow, step-by-step process.

But now I—and everyone else—live in the world where it’s possible to locate just about any piece of information immediately in the palm of my hand, which suits my short attention span well. As soon as you start even a cursory exploration into your family’s past, you see inconsistencies. Names and dates and places change throughout the records. In one place it might say a person was born in London, and in another it says Liverpool. My point is that genealogical records are neither a straight line nor consistent. Like a lot of life, it’s open to interpretation.

For example, not a single one of the US Census records I found in my investigation of the Morris sisters spelled their names correctly. Some of the records didn’t even list them at all. Each sister had about five different dates of birth. People of their time may have taken down the information correctly, but I couldn’t be certain that the Mormon librarian who read the information from these handwritten documents typed them correctly into genealogical databases.

Someone I talked to early on in the research for this book told me that genealogy is just a series of paths that lead to brick walls.

From the very beginning I understood the difficulties I faced. As a writer and essayist, I’m resourceful at finding information when I know it’s out there, but when I wanted to get to know the Morris sisters by researching their lives, I was aware that I was not going to be able to find everything I needed or wanted to know.

It’s literally impossible. A lot of genealogical information comes from census reports, and they aren’t available to the public until 72 years after they are taken. The law governing this, passed in 1978, was an outgrowth of an agreement between the Census Bureau and the National Archives. For privacy reasons, access to personally identifiable information in US Census records is restricted unless you’re the one in the record or their legal heir. So, at the time of this writing (2020), the census data available took me up to only the 1940s. The last Morris sister, Marcella, died in 1997.

So it’s a shame not to know more because census information can neatly define someone’s life. But unless I want to wait another ten or 20 years, I have to contend with what’s available. And I know that there are always going to be limitations to what we can know about the past and our ancestors, and in the future I know I will have more information—census reports and beyond—but at the same time then there will be fewer people around who will remember the sisters. Trying to find the truth in your family is a balancing act between learning facts and learning what people thought.

As I read over what I’ve written here so far, I realize that it meanders and hits several “brick walls” that genealogists talk about. Those experiences turn out to be pretty accurate metaphors for the journey I went on to learn and write about the Morris sisters. Their stories didn’t turn out the way I expected: What happened to them and what happened to me as I learned about them startled and unsettled me, and it took me to places and introduced me to people I never expected to meet. In the end the search made me reconsider how families tell the stories of the people they’re related to in order to make sense of the world and the legacy they left. And the Morris sisters were about to add a very different chapter to my own story.

__________________________________

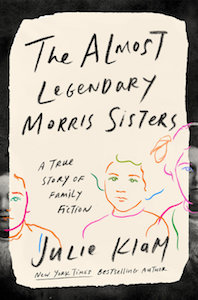

Excerpted from The Almost Legendary Morris Sisters: A True Story of Family Fiction. Used with the permission of the publisher, Riverhead Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Julie Klam.

Julie Klam

Julie Klam is the New York Times bestselling author of You Had Me at Woof, Love at First Bark, The Stars in Our Eyes, Friendkeeping, and Please Excuse My Daughter. Her writing has appeared in a variety of publications, including O: The Oprah Magazine, Rolling Stone, and the New York Times Magazine. She lives in New York City.