What Science Journalism Taught Me About Writing Fiction

Sara Goudarzi on Shifting Gears Between Fact and Fiction

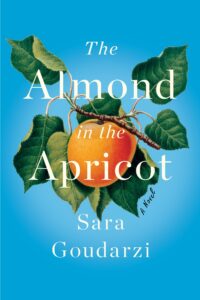

Years ago, at an informal book club gathering with friends, a fellow science journalist told me that if he were to write a novel, he’d copy the style of Haruki Murakami. This idea seemed simple enough. I had been reading stories since I was a child, sneaking in pages when I was supposed to be doing homework, during class or under the covers in the early hours of the day. Like my friend, I, too, among the works of other writers, read every new Murakami book. But when I decided to start penning my debut novel, The Almond in the Apricot, I had to no idea how to even emulate writers I admired. All those years I’d been taking in novels, I was doing so through a reader’s gaze, not a writer’s.

A veil of mystery surrounds novel writing. From the outside, it seems both ordinary and extraordinary. Ordinary because as humans, we are natural storytellers: From cave drawings to the oral tradition of storytelling, the art form is likely as old as our species. Yet it’s extraordinary because despite our natural tendency to spin tales, the task is recognizably complicated. Once you sit down to write a book, you often find yourself not knowing where to begin. And if you are lucky to find a trailhead, you’ll have to make your own proverbial path by cutting down trees and moving logs and enormous rocks out of the way.

Both my friend and I were fast writers: We worked in the same reporting room and at times churned out two to three articles a day. But, as I quickly discovered, writing a news story is different than a sprawling novel. The latter is an unruly beast, with multiple threads that need to be pulled through hundreds of pages. Methodical and forever a student at heart, I knew I needed to first understand the creative writing landscape.

To start, I browsed the shelves of my neighborhood bookstores—St. Mark’s Bookshop and McNally Jackson—and came home with two titles: How to Write a Damn Good Novel: A Step-by-Step No Nonsense Guide to Dramatic Storytelling by James N. Frey and Writing Fiction: The Practical Guide From New York’s Acclaimed Creative Writing School by the Gotham Writers’ Workshop. From those I gathered enough practical advice and basics to get going on a draft.

But these how-to books could only do so much for a person who didn’t even know the lexicon of creative writing—theme, plot, inciting incident? Soon, I enrolled in a workshop held in the basement of my neighborhood YMCA and continued taking classes for several years on and off. I often joke and say that like being president, one can’t learn how to be a novelist until one writes a novel. This might be why it can take years to complete a manuscript, because one is learning the process while trying to do the work and also overcoming the emotional hurdles of the practice, a multi-pronged approach to a multi-faceted problem.

Learning to slow down—to allow myself more words to create a mood, or capture a feeling—took effort, and a switch in thinking.

While I wrote several science articles a week, a consistent output, the pages of the novel came out in fits and starts. At times, I would steadily generate ten to twenty novel pages over the course of a week, and other times I would write nothing for months, even years, in part because I hadn’t yet learned that the writing practice it takes to produce a novel is different from that required for a shorter piece. As many would say, writing a book is a marathon, and I was a sprinter, engaged in bursts of writing with speedy editorial feedback and results that were published within a day or two, several weeks at latest.

Further, because I was both learning and writing at once, there were times when I’d have to study something and then wait weeks, or months, to be able to apply the new knowledge. Similar to how a person’s body requires a time gap between two vaccine doses to allow the immune system to learn and eventually mount a robust response, I needed my brain to make certain connections in order to understand the next idea or technique.

The lack of constraints, too, was something different. Journalism comes with word limits, facts one can’t stray from, quotes that can’t be changed and specific structures to follow—all of which help produce a story. Having the freedom to write dialogue of my own choosing, change the story direction on a whim and create fictional character attributes, while exciting, became debilitating at certain junctures. Here, I utilized journalism skills to my advantage by researching to make decisions purposefully, with reasoning behind traits, descriptions and even character and place names.

Economical writing in journalism, due to space limitations in a publication, is a necessity. In novel writing, my economical writing meant that I often got to the point too fast with too few words. Learning to slow down—to allow myself more words to create a mood, or capture a feeling—took effort, and a switch in thinking. At times, I’d force myself to sit with the pages for a long time, and try to take in the smells, sounds and contours and relay them with words; enough words to draw up a three-dimensional, movie-like scene, not just to convey a message.

Writing a novel, I learned, is slow, often underwhelming, and happens one ordinary sentence at a time, until the sentences get better, until they’re sometimes good.

There was a loneliness, too, to writing a novel. Whereas with articles, for which I spoke to sources and interacted with editors, with the novel, I was largely on my own—especially after having stopped workshopping the manuscript. And somewhere in that loneliness of the work, despite having most of a draft completed, I’d also lost the way to the finish line. At times, it felt like I was stranded so far out in an ocean that I couldn’t see, let alone make my way to, dry land.

It wasn’t until my first writer’s residency at the NOEPE Center for Literary Arts on Martha’s Vineyard that I started to figure a way out. In addition to providing time and headspace, the residency offered incredible energy powered by all the writers working at once. For those few weeks nothing outside the writing mattered. The residency participants had a common language and goal and even when we had fun it revolved around that one thing. Watching my co-residents work and learning from their experience, really reset my thinking and expectations about completing a long work.

Convinced of its magic, I attended NOEPE four times. The first time I came back home from the residency, I was able to continue writing every day for a month or two. Each time I returned to NOEPE, I was able to extend that writing practice across longer periods back in my Brooklyn apartment until I learned what it took to get to the finish line. At the end, I stopped waiting for the perfect stretch of free time or mindset. I grabbed whatever time I had, wherever I had it, no matter the distractions and kept going, every day, a little bit. “Bird by bird.”

Writing a novel, I learned, is slow, often underwhelming, and happens one ordinary sentence at a time, until the sentences get better, until they’re sometimes good and—if we’re lucky—until the act becomes extraordinary.

__________________________________

The Almond in the Apricot by Sara Goudarzi is available via Deep Vellum.

Sara Goudarzi

Sara Goudarzi’s work has appeared in The New York Times, Scientific American, National Geographic News, The Adirondack Review and Drunken Boat, among others. She is the author of Leila’s Day at the Pool and Amazing Animals from Scholastic Inc. Sara has taught writing at NYU and is a 2017 Writers in Paradise Les Standiford fellow and a Tin House alumna. Born in Tehran, she grew up in Iran, Kenya and the U.S. and currently lives in Brooklyn.