How History Has Failed to Tell the Story of the Gold

Rush Women

Brian Castner on a the Not-So-Secret Role of Women in the Klondike

In late 1898, in a snow-choked mountain pass in southeast Alaska, a woman named Anna DeGraf said a prayer to herself before she fell asleep. DeGraf was 59 years old, a widow and mother, and one of a hundred thousand stampeders trying to reach the Klondike as part of the great gold rush. Thus far on the journey she had braved rough seas and avalanches, frostbite and drowning. But at night, when she curled for a fitful sleep, she asked God for protection from a different danger. After thanking Him for the day’s deliverance, she prayed that she not be raped that night. Roving bands of men prowled the trail.

She had good reason to fear. Earlier in the journey in Skagway, a boomtown on the coast, she had fought off a group of men who tried to sneak under her tent flap. And four years earlier, when she lived in Circle City, a gold mining camp in northern Alaska, she defended herself on the regular, once beating a man with a quarter round of firewood when he entered her small cabin and barred her door, to trap and attack her in her own home.

In the worst incident DeGraf saw in Circle City, a young prostitute was gang raped by six men. When she tried to fight back, they threw her on a red-hot woodstove, causing severe burns as they forced her to sit on the cooktop. The woman managed to escape and ran to DeGraf’s cabin, where the older woman hid her in bed and then doused the lights. The men started to break in and only fled when DeGraf shot at them right through the door with her Colt revolver, which had been given to her by the constable for just such a situation.

Unsurprisingly, given the power dynamics of the time, the six men were never punished. The only justice in frontier towns like Circle City came from the miners’ meeting, an informal kangaroo court where grievances could be settled. One man would be chosen chairman, others named advocates for and against, and then all remaining constituted the jury. Majority vote won. The Circle City miners’ meeting declared the attack a “rough house,” and concluded the men didn’t mean anything by it. Note that was the same group that would later hold the racist “Coon Trial,” where a Black prostitute named May Aiken was convicted of being both. The typical punishment meted out at a miners’ meeting was banishment, which, in winter, was a death sentence.

Anna DeGraf did eventually make it to Dawson City, the ultimate destination sought by the gold rush mob. There she became an informal mother figure to the dancing girls and prostitutes. We know this because DeGraf’s descendants eventually collected and published her memoirs, titled Pioneering the Yukon. DeGraf’s wonderful book—published by a defunct small press, and long out of print—is full of these women, the abuse and beatings they endured, the suicides from depression, and even killings at the hands of their clients.

During the gold rush itself, sensational yellow journalism ruled, and the women were largely portrayed as weak and hysterical.

But you won’t read these stories in many mainstream histories. The myth of the Klondike gold rush has been sterilized and sugarcoated, reduced to platitudes about smiling Mounties and grizzled prospectors and fairy tales of exotic goodtime girls. The most popular books about the rush, written in the 1950s, emphasized how safe it was, that a man could fall asleep at the bar and his gold poke would still be there when he woke up. Even a surprising number of recent academic treatments focus on particular crime statistics—comparing violent American frontier towns to nice peaceful Canadian Dawson City—to make this same point. And if one focused only on murders reported to the police, then these statistics might reveal the truth for a subset of white men. But the era was considerably more violent and dangerous for the women.

The demographics of the stampede were stark: 95 percent men, and 96 percent white, according to a 1900 census of Skagway. Jealousy appears to have run rampant; there was plenty of gold in Dawson, but few women, and entitled men would abuse prostitutes who took other customers. Women of color, both Indigenous and of African ancestry, faced even worse exploitation and treatment. Ella Wilson, a bi-racial prostitute, was tied up in her own bedsheets and gagged to death.

When I was researching my new book, I didn’t have to dig in obscure archives to find evidence of femicide, gender-based violence, and sexual assault. They were front and center, readily available in diaries, newspaper articles, oral histories, and memoir manuscripts of the time. The experiences of DeGraf were hardly unique.

In 1898, over half the women in Dawson City were working in the sex industry in some capacity, many as a second job to make ends meet. Wages for cooks, housekeepers, nurses, and other trades available to women were so low, sex work was the only labor available that paid a living wage. Some women did “marry,” to be live-in sex workers with a single client. But this was rarely the best economic choice. Few miners were getting rich, why take your chances with just one? More prudent to mine all the miners, by working at one of the many saloons and clubs. Men would pay a dollar to dance the waltz with a “percentage girl,” so named because they made a portion of the sale. Some women used these encounters to meet clients to take upstairs, some stayed on the dancefloor and high-stepped all night, every night, two hundred dances by dawn. A scene right out of Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, in which the Man with the Thistledown Hair traps women in a nightmare of endless faux gaiety.

Written history is a product of the cultural norms of its time. During the gold rush itself, sensational yellow journalism ruled, and the women were largely portrayed as weak and hysterical, their profession hidden behind Victorian euphemisms: “sporting girls” or “soiled doves.” When Dawson City burned down, the prostitutes were the only ones to pay a price, as they were banished from public buildings, and forced to set up new cribs (what “sporting girls” called their living quarters) in “Lousetown” across the river.

The classic popular history of the gold rush is Klondike Fever, published in 1958 by Pierre Berton, who is sort-of a Canadian combination of David McCullough and Gore Vidal. It is a riotous tale; the men were manly, the women and Indigenous people little more than scenery. That many prospectors were ill-prepared for the north, and would not have survived without assistance from the local Indigenous people (some of whom the white men took in “marriage,” not always with their consent), was rarely mentioned in books of the time. Historians in the 1980s started to include women, but their actual roles were still hidden. Most women were portrayed as housewives, even though the story of the gold rush was not one of homesteading families, as in the American West. Not to mention that women, who could not yet vote, were not legally allowed to stake gold claims either. The corrective came from Lael Morgan, a professor of journalism at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Her Good Time Girls—written in the late 1990s, a time when society still blamed victims like Monica Lewinsky—broke ground by simply admitting that the sex workers were exactly that.

Not all women in the gold rush were vulnerable to second-class status or erased from the narrative. Belinda Mulrooney, the richest woman in Dawson, owned the grandest hotels in the city. Ethel Berry, named by the newspapers “The Bride of Klondike,” ran a mining operation as a full partner with her husband, and helped make the couple one of the richest and most successful to come out of the Yukon; in 2013, the family’s companies were worth $4.3 billion.

But in too many official histories, only the Ethels and Belindas seem to appear, and the average lived experience of the majority of women ignored.

__________________________________

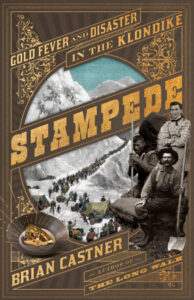

Stampede by Brian Castner is available via Doubleday.

Brian Castner

Brian Castner is a former Explosive Ordnance Disposal officer who received a Bronze Star for his service in the Iraq War. He is the author of two books, The Long Walk (2012) and All the Ways We Kill and Die (2016), and the co-editor of the anthology The Road Ahead (2017). His journalism and essays have appeared in Esquire, Wired, Vice, the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Atlantic, and other publications. He and his family live in Buffalo, New York.