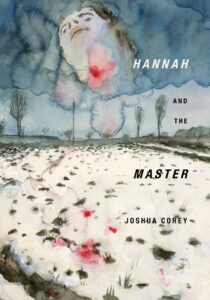

How Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger’s Relationship Can Inform Our Current Crises

Joshua Corey Investigates a “Poetics of the World” in His Latest Book

In the fall of 2011, I spent the better part of a month living in Berlin, trying to finish writing a novel while caught up emotionally in the historical whirlwind centering on that most fateful of cities. My great-grandmother and her daughters lived in Berlin in the first half of the 20th century; one of those daughters, Ilona, perished in Auschwitz in 1943. I had long been an avid reader of Hannah Arendt’s work, and had passed through a period of near-obsession with phenomenologist Martin Heidegger in graduate school. Now I found myself returning to them both, following in the footsteps of their macabre and tantalizing waltz through the 20th century as philosopher and political thinker, metaphysician and refugee, Nazi and Jew.

Two years later, while studying with Jane Bennett at Cornell University’s School of Criticism and Theory, an intuition took hold of me: we, in the early 21st century were reliving the 1930s; the lack of a meaningful response to climate change was akin to lack of meaningful resistance to the rise of fascism. Out of this feeling arose the notion that the agonistic love affair between Heidegger and Arendt was somehow paradigmatic of the struggle we face today to create a politics and poetics of “the world,” as Arendt conceived it. To recover the realm of human action in the face of an ever more tumultuous, dynamic, unconcealed, and ungrounding “earth.”

I began generating the poems and fragments that would eventually comprise Hannah and the Master. The book, a retelling of this emblematic 20th-century love story, is a kind of chrestomathy, a bricolage of fragments that surround a speculative narrative. I took the risk of reading Arendt against the grain, unearthing the remnants of Romanticism in her thought, taking her Greeks as literally as Heidegger took his. I wanted to engage history as something living—fragments of narrative that transmit by means of their telling IT MIGHT HAVE BEEN OTHERWISE. In the face of climate change, resurgent fascism, and virulent white supremacism, it felt oddly natural to turn her into the heroine of my own anti-apocalypse: a figure of resistance against the deathly mystifications of blood and soil, who, like the one-handed heroine of Mad Max Fury Road, rises redeemed from her own folly to lead the struggle against thoughtlessness and domination.

The story of Arendt’s affair with Heidegger has been told many times before and is simple enough in its outline. She grew up in an assimilated community of German Jews in Königsberg, Immanuel Kant’s hometown, and was an 18-year-old college student at the University of Marburg when she became first the student and then the mistress of the 35-year-old philosopher Martin Heidegger. A self-described “pariah,” later a refugee, she fell under the spell of “the little magician from Messkirch,” whose innovations in phenomenological thought and charismatic lectures on “the question of Being” proved to be all too compatible with the anti-Semitic Blut und Boden ideology that would soon possess Germany.

Out of this feeling arose the notion that the agonistic love affair between Heidegger and Arendt was somehow paradigmatic of the struggle we face today to create a politics and poetics of “the world,” as Arendt conceived it.

She wrote love poems to Heidegger, as well as an abstract autobiographical letter she called “The Shadows,” in which she describes herself as being trapped in inauthenticity, using language that echoes the Heideggerian jargon of gossip, curiosity, and “the they.” She laments what she feels to be an insuperable distance between herself and “reality”—a distance stemming, she implies, from her Jewishness—and yearns for “the simplicity and freedom of organic growth.”

The letter is painful to read in its self-loathing, seemingly presaging the accusation Arendt’s friend Gershom Scholem would hurl at her decades later in the wake of the publication of her book Eichmann in Jerusalem, that she lacked ahavath Israel, love for the Jewish people. Arendt’s response to Scholem was telling:

How right you are that I have no such love, and for two reasons: first, I have never in my life “loved” some nation or collective. […] The fact is that I love only my friends and am quite incapable of any other sort of love. Second, this kind love for the Jews would seem suspect to me, since I am Jewish myself. I don’t love myself or anything I know that belongs to the substance of my being.

It was “the substance of [her] being” that Arendt must have intuited that she could never reconcile with the demands for “authenticity” made by her lover-teacher, whose virulent anti-Semitism would not become fully known to the world until the publication of his so-called “black notebooks” in 2014. This is the same Arendt who would write that, “if one is attacked as a Jew, one must defend oneself as a Jew. Not as a German, not as a world-citizen, not as an upholder of the Rights of Man.”

Yet the ferociously anti-ideological Arendt is forever fighting the atavistic, tribal demands made upon her identity—the politics of dogmatic certainty in which you are either with us or against us—with the precisely honed weapon of a political ethics that boils down to this: think for yourself. Not in any preening or reflexively contrarian way, but critically, seriously, and yet retaining the capacity for mischief, even for play. Arendt may or may not have been a philosopher—a label she rejected—but she was certainly a writer, and it is the wry, ironic, yet fierce writer, unafraid of judgment, whom my book has reimagined as a romantic heroine turned warrior against fascism, groupthink, and the evil of banality that has made it so difficult for us to perceive and respond to the multilayered crises of our time.

“We want the creative faculty to imagine that which we know,” writes Shelley in “A Defense of Poetry”; “we want the poetry of life… The cultivation of those sciences which have enlarged the limits of the empire of man over the external world, has, for want of the poetical faculty, proportionally circumscribed those of the internal world; and man, having enslaved the elements, remains himself a slave.” These words remind us that the uncanny landscape of the Anthropocene is only the latest iteration of a process that was apparent to visionary poets like Shelley and Blake from the earliest stages of industrial capitalism and colonialism. What Shelley calls “the poetical faculty” is something very like the Arendtian conception of thought as “the soundless dialogue we carry on with ourselves.” Without such a dialogue we remain ignorant, blind, self-enslaved, and that much less able to carry on actual dialogue with others—the prerequisite for political action, public virtue, and freedom from domination.

Yet the ferociously anti-ideological Arendt is forever fighting the atavistic, tribal demands made upon her identity with the precisely honed weapon of a political ethics that boils down to this: think for yourself.

The book’s dialogue, as inspired by the “new kind of play” that Virginia Woolf speculated about writing, risks releasing Arendt and Heidegger into a mythic cosmos separated from their historical lives and deeds. Even as I was falling under the spell of their mad love, I tried to ironize it by wrapping it in layers of others’ narratives, from the Robot novels of Asimov and Philip K. Dick’s replicants to the story of Rahab from the Book of Joshua to the righteous fury of Mad Max Fury Road’s Imperator Furiosa.

Hannah and the Master performs a dialectical dance between history and myth. The study of history is an ethical practice; myth must be put into the service of history as a renewal of contact with the past (or “fragments of alien experience,” as Marie Luise Knott puts it); otherwise it tends toward the reactionary—the “inner truth and greatness” that Heidegger, as Rector of the University of Freiburg, attributed to National Socialism.

Walter Benjamin warned us, “The only writer of history with the gift of setting alight the sparks of hope in the past, is the one who is convinced of this: that not even the dead will be safe from the enemy, if he is victorious. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious.” Only an understanding of history, of love for the world as the scene of risk and of struggle, will help us discover how to build it anew. Only an understanding of history’s losses, and of our own losses, real and potential—of wildlife, of arable land, of breathable air, of democracy—can make something like redemption possible.

__________________________________

Hannah and the Master by Joshua Corey is available now via MadHat Press.

Joshua Corey

Joshua Corey is a poet, critic, translator, and novelist whose books include Hannah and the Master (MadHat Press) and the forthcoming novel How Long Is Now (Spuyten Duyvil Publishing). He is a professor of English at Lake Forest College and lives with his family in Evanston, Illinois.