How Don Cherry Employed the Metaphysical Body-Space to Inspire Communal Creativity

Fumi Okiji on the Practice of Listening and the Magic of an Avant-Garde Jazz Trumpeter

Don Cherry, sitting with donso n’goni between legs, is explaining the spatiotemporal confluence his body-space affords. It’s a provisional perspective, subject to change, a now-then, here-there, thinking-with, playing-with-Don Cherry. A node of our quantum intimacy, sketched out by Cherry playing the blues on West African harp.

Cherry strums a minor seventh chugging ostinato that he’d adopted from a fellow harpist, and marvels at how familiar the riff had seemed to him. How it had sent him (as he now sends us) to other times, places, and bodies, creating a scat of calabash, blues, African, black, train, racket, a rebellious rabble. Blues people and African folk (en)twinned after the fact of their noted separation. Our travels facilitated by both modern imposition and anamnestic dream and vision—a condition of having to be on both sides of the Atlantic and of a distinct African posture.

“When he played this rhythm, it was so familiar to me because I could relate it to all the blues players that I heard like T-Bone Walker, B. B. King, John Lee Hooker. It’s like the sound of the railroad train.” Cherry, playing the shunting, two-note figure on the sub-Saharan harp of hunters and storytellers while evoking the spirit of the blues, tests principles of nonlocality for the “aesthetic sociality of blackness.”

Laura Harris speaks of blackness as that which “manifests itself in what is perceived as… unruly creativity and disorderly sociality,” in constitutive distinction to the modern subject and to this subject’s “commitment to the idea of its own freedom as self-determination, as the self-conscious exercise of pure individual will, secured by self-possession.” A subject that “must at all costs defend itself… , however violent its defensive maneuvers may be.” This is what Harris tells us. And it is good to be reminded that Hegel’s infamous proclamation of African recumbence, Africa’s incompatibility with human freedom, was not only a rejection of bodies and climate/land but, perhaps more essentially, of an African way with the earth and time.

That way, so contemptible that it failed to qualify as even an underdog of universal history, is of equivocality. It is demeanor that takes the demand that we must, all of us, deal with passing, as an opportunity to maintain the dispensability of certainty and control. It’s a way with time committed to the safeguard of the uncertain. It is a way to world oriented by an inability or refusal to be supreme perquisitor of the earth and everything in it; an inability or refusal to accept self-preservation as sovereign instinct. It is a way with time that courts the unruly to preserve “non-ultimacy.” It mounts blackness as the lawlessness of the imagination, and blackness as “dispossessive force,” evincing a non-identical, nonlocal sociality of inseparability, to splice Harris with Denise Ferreira Da Silva. This, to me, is manifest so vividly by Cherry with n’goni.

*

To speak of this music is to speak for it, and that really means to speak as part of it. Not to identify with it necessarily, but to join its ensemble. To become a part of its gathering-work. Perhaps the only preparation required is to reach beyond the unease of presuming oneself part of its “anagrammatic” experiments. Peter Szendy helps me partway when he speaks of the voyeuristic pleasure he takes in listening to musical arrangements from the Romantic era, particularly those of Robert Schumann and Franz Liszt. He “love[s] them more than all the others,” he confesses, these musicians who re-tell a work, who rearrange, who put the work another way, in order that it becomes accessible to an outsider instrument or an anachronistic audience, perhaps. These “arrangers are signing… above all [to] a listening. Their hearing of a work. They… write down their listenings, rather than describe them (as critics do).”

While I don’t subscribe to this bifurcation of interpretation, setting arrangers apart from critics and other listeners, I’m intrigued by the arranger’s audacious signing of the reworked composition, their name hyphened to that of its composer; the arranger’s overcoming of any embarrassment, nominating themselves to the joint enterprise, that in a way, their arrangement inaugurates. This is the idiosyncrasy of the arranger. Their co-signing is the difference. I take the recording of a listening—that which Szendy believes to be the arranger’s distinction—to be a pervasive, perhaps even universal, phenomenon of music reception. The layering that our listening performs is the work rewriting itself, comparable to Schumann and Liszt “traverse… between original and its deformation in the mirror of the orchestra.”

To speak as part of a gathering-work is not only to place oneself in a crew. It is also to cultivate the manners of address appropriate to that site of expressive happening. The gathering-work wants your body—resonating chambers, ear drums, kinesics, proprioception. But it requires a body-space, a node, a point of contact for the transitory gathering/dispersal. To speak as part of the work is not only to provide a listening but to become a host, not for any original work-thing but for the sociality constituted by constellations of response to a call we hear after the fact, if at all. Don Cherry says that, “it’s, actually, not [his] music because it’s a combination of different experiences, different cultures, and different composers that involves the music that we play together, or that [he’s] playing when [he’s] playing alone.” Playing together or alone; playing alone, together.

Urban Lasson’s 1978 documentary, It Is Not My Music, begins with Cherry crouched in Swedish countryside cupping a whistle to his mouth, his ears pricked and tuning, so that he might get with whatever it is the birds’ descant gestures toward. This gathering-work, the first of many shared in the film, helps to establish the notion as capacious enough to take in non-human contribution. And relatedly, lays clear the precarity of the congregation, how it is at times barely there, faintly discernible; how it might, at any moment, fly away; how its refusal or inability to install immutable “central command” compounds this fragility.

*

Cherry out with the birds; Cherry and Eric Dolphy out singing with birds sends me to Cecil Taylor’s unfurl/enfold practice, and in particular to Taylor’s piano play with a branch outside his apartment window. It would be a mistake to describe this as mimicry. The gathering might more interestingly and more essentially be understood as evidence of a talent for sounding out quantum propinquity; correspondence with bird and branch toward complete communion. Of course, their practice might be explained as a training of tone and phrase, but it is also a listening to whatever it is bird or branch is straining toward. A listening to their listening.

Just as in free improvisation we often play with an ear beyond what is sonically available, away from or through dialogue and conversation, through the melding and welding of tone, toward the vestibule just beyond, or in the eye of the storm of this material and sensuous, the threshold of what Cherry understands as “brilliance” or “being in tune,” and what William Parker writes is the “the center of the sound.” Cherry’s sensuous wanting to get with the birds, his making himself of that scene, providing the body-space for a gathering to which we too are called, is also a wanting to get with whatever it is the vox mundi, the choir of questionable tuning, is looking to lose itself in.

Cherry is ambassador of a way with time and earth committed to equivocality.

Cherry is ambassador of a way with time and earth committed to equivocality. This world is driven by an inability or refusal to make an absolute exception of ourselves in relation to the earth and all that is in it. Our way with time that cultivates a stammer in order to preserve hesitance, and an inability or refusal to accept that self-preservation subdues our instinct for love feasting. Cherry the world traveler, wanderer (black and African), for whom—to borrow a fitting sentiment from Coltrane—“the whole face of the globe is community,” travels light. He tells us, “It’s actually not my music.” And demonstrates through his practice that, “[a]ll that we have (and are) is what we hold in our outstretched hands.”

It is our diasporic disposition that we have to offer, our dispersal and gathering, what we are, and all that we have. We arrive empty-handed, with nothing to bequest, no returns, no gifts to present. We arrive in counter-Odyssean empty-handedness, calling for and offering no sacrifice.

*

Thirteen minutes into Lasson’s documentary we are to accompany Cherry as he walks through a busy New York City playing his n’goni. We see how he provides the body-space for a happening that draws passers-by, in cars and on foot, into its orbit. The driver of a brown estate—sitting in or holding up traffic, children hanging out of the back-seat window—intermittently doubles up Cherry’s vocals. For how long? Ten seconds? Half a minute? I am struck by how quick they are to intimacy, the acute nature of the vicinity hit upon by the passing section. Their deep dive into the portal opening up an anamnestic communion, like an involuntary memory of the feel and taste of pressing lips that could not have possibly met theirs. These participants move out of view, but their song plays on. And the brief encounter, its impossible kiss, no doubt played on in their imaginations, and it repeats on us, too.

This diffused gathering is not confined to the live fragment captured by video—I would say that the thoughts being shared here with you have become of the lingering fugacious happening Cherry’s n’goni-extended body-space institutes. I would like to think he would insist upon my participation, my doubling, my gbenugbenu spread of our oríkì, and so I try not resist the song that breaks out here and there. His practice pulls mine into orbit, and I prepare to catch whatever is being spread.

*

The happening makes us temporarily (again), but it is not a gathering-work of agreement. Cherry’s mood doesn’t fuse. The attitude of spread and reach cannot anticipate agreement or identity. We might embrace each other now, but there are no holding patterns. Our world, and the communal series it inspires, must be incompleted by uncertainty. It must bank on the unreliability of our brilliance. Ours is a thrown together, ill thought-out reply to an awaited call, the “rub and cyclone… eye,” of a sound that we could not have possibly heard in advance. It is a practice of delay effect (echo, chorus, reverb, tremolo, flange, feedback, chop and screw) that scatters and scrambles us, until we find our tuning, until we fall, momentarily, unfathomably into that portal through which we might become everything again. A momentary but complete communion that, (often) retrospectively, orientates our material and bodily speaking with one another.

A gathering that precedes, exceeds, and questions societal bond is our aesthetic sociality. Our (under)common òrò, our always imperfect coincidence, stuttered folkic comportment. Whether in conference with birds or hosting “different experiences… cultures… and composers,” the gathering plays the range of possibilities of our shared non-identity, in defiance of the actual and its attenuation of the possible to the real—this straitening to eliminate the “mere” and “fantastic.” In defiance, we speak (alone) together on all manner of fascinating, irreal and intoxicating things. In answer to brilliant questions that are always to come.

__________________________________

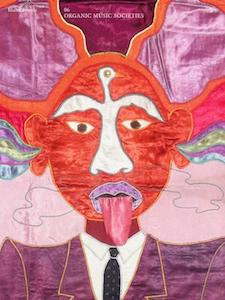

Adapted essay from Organic Music Societies, edited by Lawrence Kumpf, Naima Karlsson and Magnus Nygren. Used with the permission of the publisher, Blank Forms Editions. Copyright © 2021 by Fumi Okiji.