How Do You Write a Historical Novel About Under-Documented Lives?

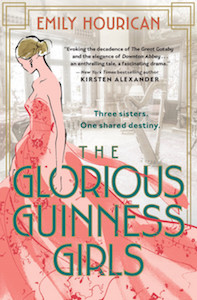

Emily Hourican on Researching Her Novel, The Glorious Guinness Girls

There aren’t any specific biographies of the three daughters of the world famous Guinness family—they crop up in broad family biographies of the large and sprawling family, of whom there are many branches and many members. But they never merit more than a few pages in these because they didn’t have political or business contributions to make. Their lives were largely the private lives of daughters, wives, mothers, and as such they were afterthoughts within the dynastic activities of the Guinness family.

So writing a novel about Aileen, Maureen and Oonagh—The Glorious Guinness Girls—became a task of assembling a kind of patchwork quilt of different bits and pieces, and sewing it all together to create a vivid whole. For me, that made the process more interesting, and creative. There were a lot of blanks to be filled in, which in turn allowed a lot of freedom. This is particularly true of the early part of their lives when they were children and then young women, before their first marriages (they had eight marriages in total between them).

They didn’t leave diaries, or none that I have heard of, and the photo albums and guest books of their very grand and sociable houses, although a very interesting record, only really come to life from the 1930s onwards.

Their lives were largely the private lives of daughters, wives, mothers, and as such they were afterthoughts within the dynastic activities of the Guinness family.

Before that, there’s a lot of guesswork involved. As is often the case when writing a fictionalized version of the lives of real people, my research became a kind of historical detective story with clues in many different places—from the diaries and memoirs of their contemporaries to newspaper gossip columns, to the novels and poetry of the era.

The first step was finding accounts of women whose upbringings would have been similar to those of the Guinness girls.

Molly Keane, the Anglo-Irish writer, was born in 1904, the same year as Aileen Guinness. She lived in a house called Ballyrankin in Wexford and although her family were nowhere near rich like the Guinnesses – not rich at all in fact – they would have inhabited the same social circles (Irish “society” at the time was so small that there was no room for tiers within it, or there wouldn’t have been anybody left to socialise with). Molly Keane has left wonderful accounts of the routines and circumstances of her upbringing in her novels— particularly her first, The Knight of Cheerful Countenance—and in her letters.

From there I went to another writer, Mary Pakenham, later Lady Mary Clive, who wrote about her childhood, split between Oxfordshire in England and Tullynally Castle in Westmeath, Ireland. Mary was born in 1907, the same year as Maureen Guinness. In her memoir Brought Up And Brought Out, she writes wonderfully about the rhythms of childhood in both places, and later, the agonies of being a debutante. This was the process whereby young women of gentle birth were launched into London society with the aim of finding a husband. It was called doing the Season, and was, as far as I can make out, a pretty mortifying process for all but the very popular few; an unashamed popularity contest—a cattle market with flower corsages and big white dresses. Maureen Guinness later described hiding in the powder room (a cloakroom) at the beginning of her Season, because she was too shy to come out.

Mary Pakenham describes the process so cleverly, with such detail, that I felt I had a real understanding of how that wretched institution worked. That was vital to me in recreating these scenes for the Guinness girls, in the knowledge that Maureen’s Season would have been that same year as Mary’s, and the two would certainly have been at the same balls and parties.

Then there were the Mitford sisters. The three eldest—Nancy, Pamela and Diana are born, each of them, the same years as Aileen, Maureen and Oonagh Guinness. And the Mitfords have of course left a wealth of material—primary sources including their own essays, letters, memoirs and diaries—and the countless biographies of them. Again, the similarities weren’t exact—the Guinnesses were far richer, and less eccentric, than the Mitfords—but there was plenty that felt applicable.

Who needs biographies with diarists like Chips Channon?

Once the Guinness girls were “out,” and doing their London Seasons, then segueing neatly into the more extravagant and determinedly frivolous scene of Roaring 1920s, there are plenty of newspaper columns in which to track their progress. Thanks to the British newspaper archives (and the Paparazzi), it’s possible to have a pretty clear idea of where they were through the later years of the 1920s and into the 1930s.

Then they also crop up from time to time in the diaries and letters of other notable figures of their time. Their cousin, Bryan Guinness, who features a great deal in my novel, wrote diaries throughout most of his life, as did Evelyn Waugh, and Henry “Chips” Channon, whose recollections were a very rich seam. Chips was an American from Chicago who married the girls’ cousin Honor, and partied hard at the very heart of the British aristocracy—and kept a wonderfully indiscreet, often very cutting, record of it.

Here’s an entry from his 1935 diary, concerning Oonagh and her first husband, Philip Kindersely: “He… is a good-looking, almost dashing, ‘Ya-Hoo’—common as clay… For two years now he has had a liaison with Lady Brougham and Vaux… Oonagh K has always pretended not to mind but her fair, stupid little heart was breaking.”

Who needs biographies with diarists like Chips Channon?

Some of the associated characters of their lives were also worth tracking. Maureen’s first husband, Basil Blackwood, was a hero to his male contemporaries, some of whom (luckily for me) were writers. The poet John Betjeman was a friend from their days at Oxford together, and wrote “In Memory of Basil, Marquess of Dufferin and Ava,” on the occasion of his death in 1945, with the lines “you my friend were explorer/ and so you remained to me always/ Humorous, reckless, loyal –/ my kind heavy-lidded companion.”

Other sources were even more fleeting yet evocative, like this poem by playwright Noel Coward, written in 1938, called “I Went To A Marvellous Party,” which includes the lines, about Maureen Guinness,

Maureen disappeared

And came back in a beard

And we all had to guess at her name

Finally, there are the novels of that era. Novels aren’t, of course, “fact,” but very often they carry the flavour of their time even better than a diary can. The work of Anglo-Irish writers such as Molly Keane, Elizabeth Bowen and JG Farrell, and the 1920s novels of Evelyn Waugh (his first, Vile Bodies, is dedicated to Bryan and Diana Guinness), Patrick Hamilton, Henry Green and Nancy Mitford bring to life a time, a place, a way of talking and behaving that would otherwise be lost. For a strong sense of what London in the 1920s was like—the sounds, smells, sights—I’m indebted to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories of Sherlock Holmes, and Margery Allingham’s thrillers, which describe the London smogs most brilliantly.

All of these varied sources were invaluable in piecing together my version of what the Guinness girls’ lives were like. It was like a recipe—a pinch of this, a pound of that, a dash of the other—all adding, up, I hope, to something rich and compelling.

_________________________________________________

Emily Hourican’s The Glorious Guinness Girls is available now via Grand Central Publishing.

Emily Hourican

Emily Hourican is a journalist and author. She has written features for the Sunday Independent for fifteen years, as well as Image magazine, Condé Nast Traveler and Woman and Home. She was also editor of three magazines. Her debut novel, The Privileged, was shortlisted for the 2016 Irish Book Awards in the Best Commercial Fiction. Emily was born in Belfast, grew up in Brussels, and went to school in University College Dublin, where she earned a Masters in English Literature. The Glorious Guinness Girls is her latest novel. She lives in Dublin with her husband and three children.