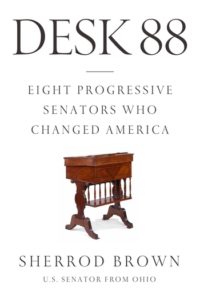

How Did a Single Desk in the Senate Become a Focal Point for American Progressivism?

Sherrod Brown on the Unlikely History of Desk 88

Finally, it was the freshmen Senators’ turn. Ten of us—nine Democrats and one Republican—wandered around the big hall, surveying where we might sit. We talked about location: which row to sit in, whom to sit next to, which desk was closest to the front—it was all perhaps a bit too reminiscent of high school.

It suddenly occurred to me: there were no bad places to sit. No pillars to sit behind. No obstructed views. We were on the floor of the United States Senate.

At the freshman orientation a couple of months earlier, senior senators had shared with us some stories and traditions of the Senate. One of those traditions—reminiscent of middle school—is that most senators at some point in their careers carve their names in the drawers of their desks in the Senate chamber.

So, a bit sheepishly, with these carvings and this history in mind, I pulled out drawer after drawer in desk after desk, pushing aside the clutter of stationery, legislation printouts, and committee reports to read the names that were carved on the inside bottom of each drawer.

At the fourth desk I approached, something felt different. I knew almost every name carved in the drawer. I read through the names of Desk 88—Black of Alabama, Gore of Tennessee, Lehman of New York, McGovern of South Dakota, and—I broke off, curious. Between McGovern and Ribicoff of Connecticut, the desk drawer had only one word: Kennedy. No state, no first name. I called out to Senator Edward Kennedy and asked him to look at the desk. “Ted, which brother’s desk was this?”

He looked down at Desk 88. “It must be Bobby’s,” he said. “I have Jack’s.” I had found my Senate home. My chief of staff, Jay Heimbach, informed the clerk of the Senate that Desk 88 was the one I wanted.

What drew me to the names at Desk 88 was the idea that connected them: progressivism. It’s a political ethic that had driven not only my votes in Congress (I joined the House of Representatives in 1993 and reached the Senate in 2007) but also my decision to run for office in the first place. Over the past century, progressives have stood for labor rights, civil rights, stronger antitrust laws, women’s rights, a higher minimum wage, health and safety regulations, a steeply graduated income tax, child labor protections, and workers’ compensation. More recently, progressives have fought for abortion rights, universal health care, strong environmental laws to combat climate change, equal rights for gay and transgender Americans, gun safety laws, consumer protections, and a ban on political contributions from corporations.

Progressives of all generations, and certainly those who sat at Desk 88, share a revulsion at injustice and wage inequality and wealth disparity; most progressives are bound together by a deep respect for the dignity of work and, in Tolstoy’s words, “the fundamental religious feeling that recognizes the equality and brotherhood of man.” Progressives typically share a common suspicion of concentrated power, especially private power.

Some of those who sat at Desk 88 played crucial roles when the country was in the midst of progressive times. Others, at great risk to their political careers, espoused progressive principles in more difficult eras, when the country was in a particularly conservative, sometimes dark and angry mood.

Often the great achievements of the occupants of Desk 88 took place somewhere else—in the ornate hearing rooms of the Russell Senate Office Building, in union halls or church basements, at veterans’ lodges or in school auditoriums. But sometimes—and there are examples in this book—the desk itself bore witness to a turning point in progressive history. The greatness of these senators was most evident when they spoke out and fought against the special interests that have always had too much influence in our government.

Like most legislators throughout U.S. history, the senators of Desk 88 have been disproportionately white and male. The Senate historian believes that no woman has yet called Desk 88 hers. Even as this book celebrates the men who articulated and achieved progressive goals, its final chapter will acknowledge the work still to be done and highlight a new generation of progressives working for equality and opportunity.

In short, the fight for equality is what defines a progressive.[/pullqote]

Progressive movements arouse the public as they fight the abuse of power by oil companies, Wall Street, the tobacco industry, and huge pharmaceutical firms. They challenge the dominance of the big banks and Big Oil and the gun manufacturers, and they attack entrenched racism and sexism. They want to reform a broken system under which powerful interest groups almost always have their way in the halls of Congress and in state legislatures across the country. They speak out against what William Jennings Bryan labeled “predatory wealth.”

Fundamentally, progressives want an America where the voiceless are heard in the government, where those without wealth or power have a government that represents them. And as progressives fight for civil rights and women’s rights, for LGBTQ rights and labor rights—in short, the fight for equality is what defines a progressive—we know that progress has never come easy, even in the United States of America.

Almost two decades ago, I addressed a Workers Memorial Day rally in Lorain, Ohio. I stood in front of a fifty-foot-high pile of black iron-ore pellets where the Black River empties into Lake Erie. After the event, the steelworker Dominic Cataldo handed me a lapel pin depicting a canary in a birdcage. “This pin,” he told me proudly, “symbolizes our decades-long fight for worker safety.” Ever since, I’ve worn my canary pin to honor the millions of Americans who have fought for traditional American values, and to celebrate the dignity of work. In the early days of the twentieth century, more than two thousand American workers were killed in coal mines every year. Miners took a canary into the mines to warn them of toxic gases; if the canary died, they knew they had to escape quickly. It was a warning system built out of desperation. With no trade unions strong enough to help and no government that seemed to care, the miners were on their own.

Americans—in their churches and temples, in their union halls and neighborhood organizations, in the streets and at the ballot box—fought to change all that. Our progressive forebears convinced our government to pass clean air and safe drinking water laws, to approve auto safety rules and protections for the disabled, to enact Medicare and civil rights and consumer protections, to create Social Security and workers’ compensation, to sponsor medical research and build airports and highways and public transit and municipal water and sewer systems. Every accomplishment, every step forward, came in the face of entrenched and powerful opposition—from Big Oil and Wall Street, from tobacco companies and pharmaceutical firms, from industries that poisoned our air and fouled our rivers. Tens of millions of Americans now live longer and healthier lives because activists all over our nation fought for our American values of fairness and economic justice.

History shows that progressives—and progressivism—are at their best when they appeal to a sense of community. To progressives, it was always about public health and public safety and public education and public works. But too often, in modern America, we see, as John Kenneth Galbraith noted, “private opulence and public squalor.” We see a government that provides tax cuts for those who least need them, and starves public services—medical research, city parks, health care, child care, water and sewer systems, public transit, neighborhood schools, rural broadband—for everyone else.

Progressivism is not just about government playing a positive role in people’s lives—though it is that, from civil rights to workers’ rights, from clean air to support for children and the disabled, from minimum wage to Medicare. It is about more than the government standing with those with less privilege. It is also about a civic culture defined by fairness and reason, and tolerance for opposing viewpoints. About voting rights and fair play. About campaigns where the candidate with the most money does not necessarily win. About a political system that encourages participation. About a government and an economic system that work to generate safety and opportunity for the many, not concentrate wealth in the hands of the few. And about the dignity of work.

The lessons we learn from Desk 88 are still instructive for our country. Consider the question of war and peace. On March 7, 1968, Robert F. Kennedy stood at his desk on the floor of the United States Senate to deliver his strongest and most poignant speech in opposition to the Vietnam War. “Are we like the God of the Old Testament,” he thundered, “that we can decide in Washington, D.C., what cities, what towns, what hamlets in Vietnam are going to be destroyed?” He rejected President Lyndon Johnson’s justification for fighting that war, that if we don’t engage with and defeat the Communists in Vietnam, they will overrun all of Southeast Asia, then invade Hawaii, then attack San Francisco. That same reasoning, New York’s junior senator asserted, was used by the Soviets and the Nazis in 1939 and 1940 when they invaded, conquered, and then divided up Poland and the Baltic states.

More than three decades later, Johnson’s arguments were employed, this time by a Republican president, in justifying an attack on Iraq, the expansion of government wiretapping and library searches, fast-track trade-negotiating authority, and tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans—of course, any excuse will do. We must fight them over there, President George W. Bush and Vice President Richard Cheney warned us, so we don’t have to fight them here. Neither Presidents Kennedy and John-son in Vietnam nor President Bush in Iraq had heeded the words of the nineteenth-century Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz, who wrote that, in war, a nation should “never take the first step without considering what may be the last.”

With great skill, conservative leaders have learned to distract the public with fear and prejudice because they know they lack public support on the fundamental issues.

The misuse of fear can shape domestic politics as well. In his last address at the National Prayer Breakfast, in February 2016, President Obama instructed us: “Fear does funny things. Fear can lead us to lash out against those who are different or lead us to try to get some sinister ‘other’ under control. Alternatively, fear can lead us to succumb to despair, or paralysis, or cynicism.”

Most of the time, the fear of change has the upper hand in politics. Ralph Waldo Emerson told us that history is a contest between the Conservators and the Innovators. Conservators—those with privilege and wealth, who want to hold on to what they have—are vastly outnumbered. But they long ago figured out how to consolidate power: exploit the fear of people who would benefit from change by convincing them that change is too risky. Conservators routinely warn the public that big government—those people in Washington—will take away what they earned with their hard work: a small house, a moderate income, a barely middle-class lifestyle. “Fear always springs from ignorance,” Emerson noted. So often, those who have little often line up with the Conservators.

With great skill, conservative leaders have learned to distract the public with fear and prejudice because they know they lack public support on the fundamental issues. They attack government regulation as they feed Wall Street. They talk about crime as they underfund public schools. They rail against government spending on the least privileged as they lavish tax cuts on the most privileged. They ridicule welfare recipients and food stamp beneficiaries as they pad corporate welfare accounts and subsidize large corporate farms. At their best, the senators at Desk 88 fought back against this fear-mongering. “Self-anointed patriots,” as Tennessee Senator Albert Gore, Sr., called them, raise the specter of Communism, terrorism, or immigration to make people forget that the conservative elite are, in fact, taking advantage of them.

Fear has played a central strategic role in the Republican Party since at least World War II. It was Communism in the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. It was crime in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. It was the fear of terrorism in the George W. Bush years. It was integration and immigration—people we do not know, religion we do not understand, and cultures we find alien—through much of our history.

Perhaps it should not have shocked the GOP establishment when, after decades of Republican dog whistles about race via “states’ rights” and being “tough on crime,” Donald Trump’s bark captured the Republican base in 2016. Trump’s ideas, after all, were not so different from those of others in his party—just less polished. During the desperate flight of hundreds of thousands of refugees from the Middle East in 2015, presidential candidate Jeb Bush—the national media’s Designated Thinking Man—proclaimed we should accept in our country only “Christian Syrians.”

A few days later, Trump said that our government should bar all Muslims from entering the United States. Fido’s yap yielded to the Doberman’s full-throated roar. Of course, Trump was more explicit than established Republicans wanted him to be in his racist, xenophobic, and misogynist comments. But the overwhelming majority of Republican officeholders, many of whom disavowed his individual comments, endorsed him nonetheless. Some even endorsed him, unendorsed him, then endorsed him again. And almost unanimously they have continued to enable and support him well into his presidency.

*

I came to the United States Senate at the close of an era. Voters in 2006 spoke a resounding “no” to the conservative Bush-Cheney policies of deregulation, tax cuts for the most privileged, runaway budget deficits, giveaways to favored corporations, and expansionist foreign policy. The conservative era, ushered in by the Reagan landslide of 1980, had run its course, and had imposed a substantial cost on our country.

The far right had shown contempt for a government of the people, for the people. Beginning with Republican House Majority Leader Tom DeLay—with his K Street Project—conservatives used government to enrich their political allies. Huge tax cuts were bestowed on the super-wealthy and on favored Washington special interests. Medicare was partially privatized, reaping tens of billions of dollars for well-connected pharmaceutical and insurance companies. An energy bill written by the Koch brothers and their billionaire allies was signed into law, further enriching much of the Republican money base. Friends of the president and the vice president made billions of dollars providing services in Iraq, most notably Vice President Cheney’s former employer Halliburton, which received tens of billions of dollars in unbid contracts. And military spending—but not veterans’ benefits—knew few limits.

The fervor behind tax cuts for the richest Americans—and cuts in spending—robbed our nation of much more than reliable highways and bridges.

The last quarter century was a period of exploding budget deficits and, perversely, a starving of many government services, at least those programs that didn’t serve K Street. It was a time of burgeoning trade deficits and a shrinking manufacturing workforce. The damage is especially evident in our cities, rural areas, and inner-ring suburbs—where crumbling bridges, potholed streets, badly maintained water and sewer systems, and decaying public transit systems endanger both safety and prosperity.

In the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s our country built some of the best public works in world history. Yet despite the fact we are a wealthier country today, we have failed to modernize or even maintain them. We as a nation spend 2.4 percent of our gross domestic product on infrastructure, while the European Union spends more than 5 percent, and China expends 9 percent on domestic and foreign projects.

The fervor behind tax cuts for the richest Americans—and cuts in spending—robbed our nation of much more than reliable highways and bridges. The neglect of public health, the compromising of worker safety and environmental regulations, and the shredding of protections for consumers and the investing public have all imposed dire costs on our country. Today, millions of poor, working class, and middle-class students are unable to acquire an education without taking on oppressive debt. My wife, Connie Schultz, whose utility-worker father had little money to send four children to college, graduated from Kent State University with less than $1,200 in debt in 1979. In those days, tuition costs were lower because state governments provided more funds for state universities, Pell Grants were more plentiful, Stafford Loans more accessible, the GI Bill more generous. The cost of attending Kent State for in-state students today? Twenty-two thousand dollars per year.

The budget deficit exploded during the Reagan-Bush years, reaching one billion dollars a day. The Clinton years—with tax increases, spending cuts, and economic growth—saw the huge budget deficits turn to surplus. But then, beginning in 2001, the new self-professed conservative in the White House, George W. Bush, again ran up billion-dollar-a-day deficits with tax cuts for the most privileged, the unpaid-for war in Iraq, and a giveaway to the pharmaceutical and insurance industries in the form of a Medicare drug benefit.

What did these deficits achieve? To get some perspective: during the eight years of the Clinton presidency, the nation enjoyed a net increase of twenty million private-sector jobs; during the eight years of the second Bush presidency, the nation saw a net increase of fewer than one million private-sector jobs.

And something else happened: an expanding chasm between the very rich and the middle class. The link between worker productivity and worker pay began to weaken in the 1970s, with the second Clinton administration an exception to the pattern. During the mild economic growth of the Bush II years, that link was severed. Profits went up, but wages didn’t; productivity rose dramatically, yet workers’ security was compromised. Average income for American workers, adjusted for inflation, dropped $2,000 in the first seven years of the Bush presidency, and that was before the economic meltdown. And while the median wage was flat, the median wage for African American workers sharply declined. Though the Obama presidency and Congress saved America from economic catastrophe, and began a turnaround that has lasted a decade, the forces that widen in-equality remain unchecked. Simply put, workers—and this includes as many as three-fourths of employed Americans—are not sharing in the wealth they create for their employers.

Conservatism has had no answer to the question of the growing gulf between the most privileged and everyone else; or more precisely, it has had the same answer it always did: more deregulation, more tax cuts for the wealthy, more privatization of government services. All were tried in the Bush years. All made the problem worse.

Conservatism has had its chance, winning far more political battles since 1980 than it lost—some at the ballot box, some in state legislatures, some in the halls of Congress, and others in an increasingly conservative, activist Supreme Court. Republicans have been a majority on the United States Supreme Court for more than four decades. But conservatism today is more about interest group politics than a coherent value system. Voters felt a betrayal as interest group conservatism—especially in the corporate wing of the Republican Party—overreached. In the Bush years, the Medicare drug law was written by and for the pharmaceutical companies. The energy bill was drafted by and for oil and gas interests. Health insurance rules were essentially promulgated by and for the insurance industry. And trade agreements were negotiated by and for Wall Street and the multinational corporations that were reaping record profits by outsourcing jobs.

Of course, conservatives’ trickle-down economics did benefit some people: executives with strong political ties. More lobbying contracts, more lax regulation, and more goodies and perks for the favored few all but guaranteed campaign contributions that kept the conservative, increasingly southern Republicans in power. All good for monied Washington interest groups, but not so much for a beleaguered American public.

Three years into the Trump administration, Republicans—with a minority of voters behind them, but assisted by redistricting, voter suppression, the arcane electoral college, and bold power plays by the Republican leader in the Senate—still hold on to power. Far more Americans voted for a Democrat for president in 2016, far more Americans voted for Democrats for the Senate in 2016 and 2018, yet Republicans control the Senate, the White House, and the Supreme Court. But their power will not last.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Desk 88: Eight Progressive Senators Who Changed America by Sherrod Brown. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux on Nov. 5, 2019. Copyright © 2019 by Sherrod Brown. All rights reserved.

Sherrod Brown

Sherrod Brown, Ohio’s senior U.S. senator, has dedicated his life in public service to fighting for what he calls “the dignity of work”—the belief that hard work should pay off for everyone. He resides in Cleveland with his wife, Connie Schultz, a Pulitzer Prize–winning columnist and author. They are blessed with a growing family, including three daughters, a son, and seven grandchildren.