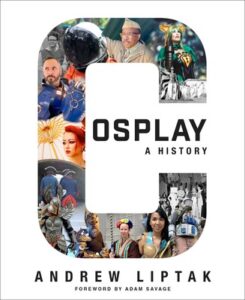

How Costumes and Conventions Brought Sci-Fi Fans Together in the Early 20th Century

Andrew Liptak on the Origins of Cosplay

Science fiction has a deep, rich past—one that sees its roots stretch back to ancient times. Fans and scholars often point to Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus as its most recognizable origin point, followed by the works of authors like Jules Verne, H. G. Wells, Edgar Allan Poe, and many, many others. In the early twentieth century, one enterprising editor, Hugo Gernsback, founded Amazing Stories magazine, the first publication dedicated to the types of stories that would come to be known as “science fiction.” Born in Luxembourg in 1884, Gernsback immigrated to the United States at age twenty and quickly set up a magazine called Modern Electrics, which featured articles and fiction geared toward radio enthusiasts, as well as parts that they could buy.

Gernsback was already a fan of a growing body of fiction featuring fantastic technologies written by authors such as Shelley, Wells, Verne, and Poe, and he began to include short, science-driven stories in his own publications, including his own serialized novel, Ralph 124C 41+.

Gernsback wasn’t the first editor to solicit and include science fiction in his publications, but he recognized the appetite from technologically minded readers, who yearned to imagine what the future might hold—especially what gadgets they might someday use. To feed that appetite, he founded Amazing Stories in 1926.

Amazing Stories was a lightning strike in a primordial pond: a jolt of energy to the right set of ingredients. Its bold, garish covers and fantastical contents attracted many would-be science-fiction writers and fans, and it quickly became a hit on newsstands.

What makes this moment even more significant is that it demonstrated that a fan’s expression of their love of science fiction wasn’t entirely text-based.Gernback quickly added other serials to his lineup, such as Air Wonder Stories, Science Wonder Quarterly, and Scientific Detective Monthly. In his magazines, Gernsback introduced a useful feature for his readers: a letter column that allowed them to respond to stories or one another and locate nearby fans.

Gernsback wanted to build a durable audience that would remain engaged with his publications (and thus continue to buy them) and in 1934 launched a fan club called the Science Fiction League, with local chapters scattered around the world. The desire to meet and interact with other fans grew beyond Gernsback’s network; groups like the Futurians in New York City and the Lost Angeles Science Fantasy Society have their roots as his club’s chapters, but eventually established their own identities, These groups brought together science fiction fans for regular meetings to socialize, discuss their favorite stories, and critique one another’s own stories. Out of these fan clubs emerged some of the genre’s foundational individuals, such as Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, Frederik Pohl, C. L. Moore, and Forrest Ackerman, who encouraged and competed with one another to break into the growing field of magazines.

*

The emergence of organized fandom led to larger gatherings: conventions that brought together hundreds of fans from all around the country, and eventually from around the world. The 1939 World Science Fiction Convention’s organizers drew around two hundred fans and writers from all over the United States, including the likes of Asimov and Bradbury, as well as professionals like Astounding Science Fiction editor John W. Campbell Jr. Also among their numbers were fans like Ackerman and Douglas—who went by the Esperanto name Morojo—soon to revolutionize costuming with cosplay.

The pair hailed from Los Angeles, California, and had each been heavily involved in the local science-fiction scene. Ackerman was born in 1916 and fell in love with science fiction at age ten when his mother gave him a copy of Gernsback’s Amazing Stories.

Ackerman jumped feet-first into fandom, quickly amassing a personal library of dozens of other science-fiction magazines. He began writing stories of his own, although he never seriously pursued a career as a science-fiction writer as other fans like Asimov and Bradbury did. Instead, he began writing letters to magazines and fellow fans. In the 1930s, he set up a fan club of his own—the Boys’ Scientifiction Club—wrote for various science-fiction fanzines, and was an early member of the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society. He’s widely considered to have coined the abbreviation “sci-fi.”

It was within this circle of science-fiction fans that he caught the eye of Myrtle Rebecca Douglas in 1937. They were both attendees of a world language meeting for the fictional language Esperanto, and they had a lot in common.

Douglas was a devoted science-fiction fan, and the two of them collaborated on a fanzine called Imagination! the LASFS’s official publication. Ackerman later recalled that she helped produce the printed edition: “She was a real pro in the typing, stenciling & mimeoing departments. An excellent proof-reader. And she was a staunch supporter of nonstoparagraphing & Ackermanese, god bless her—I say, fully conscious of the fact that she was an atheist.”

But she was also interested in costumes, and when she and Ackerman traveled across the country to attend the 1939 World Science Fiction Convention, she created two costumes for them to wear for the event. “She designed & executed my famous ‘futuristi-costume’—and her own—worn at the First World Science-Fiction Convention, the Nycon of 1939.” The costumes were based on a film that the pair had enjoyed: an adaptation of H. G. Wells’s novel Things to Come.

Ackerman’s costume consisted of a green satin cape and a long-sleeved, button-down yellow shirt emblazoned with his nickname, 4SJ. In his memories of the convention, Ackerman noted that they had based the costume on Frank R. Paul’s artwork and the film Things to Come, and he described it as being like “mild-mannered Clark Kent, going into the telephone booth and coming out as Superman.”

In his book Bradbury: An Illustrated Life, Jerry Weist wrote that “this was really the beginning of costumes and the masquerade at conventions.” The pair were surprised that they were the only people dressed up in costume, and [that] the reaction was one of confusion, according to Ray Bradbury’s biographer, Sam Weller, who told me that “People asked them, ‘What the heck are you doing?’”

“I just kind of thought everybody was going to come as spacemen or vampires or one thing or another,” Weller recounts Ackerman saying in The Ray Bradbury Chronicles: The Life of Ray Bradbury. “We walked through the streets of Manhattan with children crying and pointing: ‘It’s Flash Gordon! It’s Buck Rogers!’”

Douglas and Ackerman demonstrated that they could also express that fandom in the real world.“I even got the nerve to go out to the World’s Fair in it; they had a platform with a microphone, and if you were from Spain, or from Sweden or France or Germany or wherever, you could come up and greet the world in your native language. So I got this quixotic notion to go up and speak in Esperanto to the world, and say that I was a time traveler from the future, where we all spoke this language.”

In one picture, Ackerman is looking to the camera, a grin plastered across his face, dressed in high boots, uniform pants, and a textured vest over a collared shirt. The entire outfit makes him look like one of those characters from the covers of the pulp magazines. In another, Ackerman towers over Douglas, who is wearing an advanced-looking dress. In his memoir, The Way the Future Was, science-fiction editor Frederik Pohl recounted the scene: “We met Californians like Forrest J. Ackerman and his feminine sidekick Morojo, both of them stylishly dressed in fashions of the Twenty-First Century and turning heads in every cafeteria they entered.”

This moment is a notable one: while this wasn’t the first gathering of fans, it was the first large-scale convention for which fans from all over the country assembled, demonstrating to all involved (and also those unable to attend) that they weren’t alone in their interests. During these early days, science fiction’s visual depictions came through the artwork that graced the cover of pulp magazines and the occasional science-fiction film, like Metropolis or Things to Come. Moreover, while people certainly dressed up for costume parties and masquerade contests prior to this moment, the convention appears to be the first time that we see the two phenomena together.

What makes this moment even more significant is that it demonstrated that a fan’s expression of their love of science fiction wasn’t entirely text-based. While fans wrote their own magazines, artwork, stories, and letters to one another, each of which contributed to the original framework that is fandom, Douglas and Ackerman demonstrated that they could also express that fandom in the real world.

Moreover, they wouldn’t be alone.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Cosplay: A History by Andrew Liptak. Copyright © 2022 by Andrew Liptak. Available from Saga Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc