How Cooking Frees My Mind to Think About Writing

Since I Was a Child, I've Been Obsessed with Food in Literature

I love food. I love to eat it, prepare it—and read about it. Even before I was out of the crib, I had a gastro-literary fixation: the drawing of bread in Richard Scarry’s Busy World, Busy People, which I demanded to see daily. Once I’d graduated to print, obsession reached a new, active level. The Little House books, for instance, had me hand-churning butter (with an electric mixer), grinding coffee in an antique mill, and trying to create candy by drizzling syrup on snow. “Hang on, Ma,” I said one weekend, mixing water with cornmeal to make griddle cakes. “Patience is a virtue.”

“We buy pancakes in the frozen food aisle in this century,” my mom said, “and don’t call me Ma.”

I remained undaunted. Food, fiction taught me, could be anything. Temptation: the Turkish Delight that lured Edmund to the White Witch in Narnia. Individuality, like Harriet the Spy’s tomato sandwiches (which I tried very hard to like but couldn’t). It was comfort and enemy in Judy Blume’s Blubber—a book to which, as a chubby tween, I related all too well. It was magic in A Little Princess—a starving child goes to sleep pretending she has provisions and wakes to tea, rolls, and rich savory soup. In Bright Lights, Big City, bread is redemption to a cocaine-addled anti-hero. In Heartburn, when eight-months-pregnant Rachel Samstat’s husband cheats on her, she turns to tubers. “Nothing like mashed potatoes when you’re feeling blue,” she observes.

Whether my love of food made me notice it in fiction or its magical ubiquity in fiction made me notice food—which came first, the roasted chicken or poached egg?—the two braided like a challah. As soon as I could reach the stovetop, I started to cook: my dad taught me to make mushroom soup with chives, scrambled eggs with dill and caramelized onions. In high school, when my mom returned to work, I cooked for my siblings. In my twenties, to support my expensive writing habit, I took jobs as waitress, hostess, prep chef. I earned scars, sliced my hands cutting lemons and baguettes—visiting the ER enough that one doctor, stitching me up for the third time, suggested I get a job involving nothing sharper than a stapler. I could have; I had an English BA from Kenyon College. But I loved cooking: the challenge of getting good meals to people on time; staff banter; the physical rhythm of food preparation, which freed my mind to think about writing. Cubing potatoes or chiffonading basil, I rehearsed lines for the story I’d work on that night.

The habit stayed with me. After grad school, teaching at Boston University and writing my first book, I baked. I thought I was making tarts and Linzertorte because my novel, Those Who Save Us, was set in a German bakery, and I wanted to know what my heroine Anna felt, down to her fingers’ permanent cracks from flour. And that was true. But it was also because cooking was a containable task: unlike writing a novel, which takes me three to five years, you know within three to five hours whether your dish is a success or a failure.

For my third novel, The Lost Family, I raised the bar: I set part of the novel in a 1965 Manhattan restaurant.

“I earned scars, sliced my hands cutting lemons and baguettes—visiting the ER enough that one doctor, stitching me up for the third time, suggested I get a job involving nothing sharper than a stapler.”

In childhood, I’d had a restaurant in my basement called “Faster,” where I served my entrapped parents Play-Doh dishes fired in my EZ Bake oven. Part of me had always wanted to be a restaurateur/chef, like The Lost Family’s protagonist, Peter Rashkin. But having observed real chefs in action, I didn’t think I had the chops for it.

Or did I?

For a whole summer, researching The Lost Family, I got up and made bread. First a simple artisan loaf. Then baguettes à la Julia Child, which meant hurling ice cubes into the oven for crisp crusts. I made pain de mie and Vollkornbort, German seed bread, and while I waited for dough to proof, I devoured chef memoirs: Anthony Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential, Jacques Pepin’s The Assistant; Gabrielle Hamilton’s Blood, Bones and Butter; Ruth Riechl’s Tender at the Bone. Why hadn’t anyone told me how funny chefs were, how suspenseful their stories? It maybe shouldn’t have surprised me: chefs live for passion—for food—and outside the box. Their books were as compelling as any thriller.

One morning my fiancé came downstairs to find me barricaded behind cookbooks as usual: The Betty Crocker New Picture Cookbook, The New Ford Treasury of Favorite Recipes from Famous Restaurants. “You know what would be really cool?” he said. “Since your novel’s set in a restaurant, it should have menus.”

Ah ha.

I began inventing and kitchen-testing recipes—on him. The Lost Family’s restaurant, Masha’s, features German-Jewish fusion with a Mad Men twist, meaning the food would be brown and saturated in whiskey. But Peter, my hero, was a curious and exacting fellow, on the cutting edge of farm-to-table gastronomy, a pre-pioneer of nouvelle cuisine. Voila: everything in our garden went into The Lost Family. I’d planted too much cabbage? Miniature Cabbage Rolls with Mustard & Sweet & Sour Dipping Sauce. A tangle of string beans became Green Beans Amandine; our beets were Pickled with Horseradish Creme Fraiche. Our plum tree produced Plum Tart with Roasted Walnut Crust & Kirsch-Infused Whipped Cream.

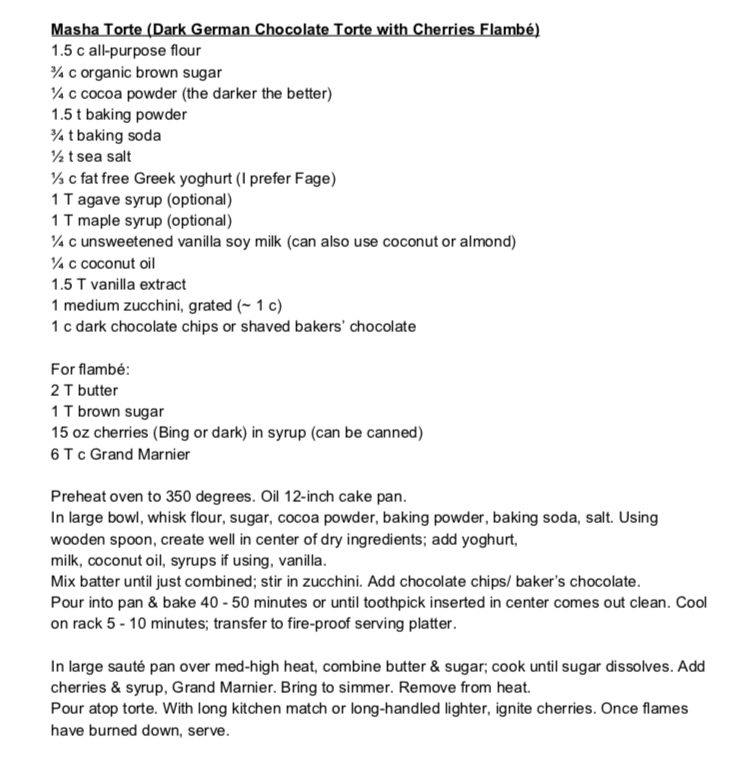

There were some disasters. The Plum’splosion, when I forgot a vat on the stove and found the kitchen so spattered with exploded fruit that it looked like a murder scene. The Chicken Kiev that squirted off the counter into our dog’s waiting mouth. And the Masha Torte Mishap. The Masha Torte is an inside-out German chocolate cake with cherries flambe; I was astonished when my first attempt, removed from the oven, was a thing of glistening beauty. Jim and I watched it cool from a few feet away. “It’s gorgeous,” he whispered. “I never dreamed I’d make something that amazing,” I breathed. While I was transferring it to its serving platter, it slithered nimbly off onto the floor.

I relearned lessons in resilience, patience, the inevitability of failure. My new burns and scars concretized my character’s kitchen-centric world. I wrote much of the novel in my head while kneading and slicing, dicing and stirring. And I received an unexpected gift: memory. One afternoon, standing in my steamy August kitchen labeling canning jars, I suddenly saw my grandmother Ray’s, my dad’s mom’s, handwriting on similar labels. Had she made this same chutney, the condiment I thought I’d invented? I called my aunt. “Oh, yes,” she said. “You would’ve been too young to remember, but Grandma had a whole secret garden down by the Long Island Sound, and every August she canned all the fruits and vegetables.”

A few days later, my grandmother’s recipes, written on handled-until-soft index cards in the spiderweb handwriting I remembered, arrived in my mailbox.

Food in life and books means so many things: Connection. Culture. Inheritance. Science and mystery. Love. And for me, a bridge between the fictional and real. Cooking food from books I love is a way of making the imaginary real, something I can hold in my hands—and eat. It’s magic, a way to make the imaginary come true.

Jenna Blum

Jenna Blum is the New York Times and number one international bestselling author of the novels Those Who Save Us and The Stormchasers. Her most recent novel is The Lost Family. She was voted one of the favorite contemporary women writers by Oprah.com readers. Jenna is based in Boston, where she earned her MA from Boston University and has taught fiction and novel workshops for Grub Street Writers for 20 years.