14 Famous Writers on Whether or Not to Have Kids

Because Everybody Has an Opinion

Are children the enemy of writing? Are children the saviors of writing? Does writing ruin you for parenthood? Does parenthood ruin you for writing? Do children launch you into new heights of creativity? Do children sap your energy until you are a talentless blob? How many children should you have? Can only men be art monsters? Should only women be art monsters? Is it perhaps different for everyone?

These are only some of the many (many) questions we ask ourselves, and each other, and strangers for whom it is probably quite intrusive, actually, about children and writing. Of course, the way we approach this topic is often gendered—if you’re a female author, you’re much more likely to be asked about your feelings around parenthood and writing—but increasingly, it’s become a subject of discussion for all kinds of writers. Everyone has an opinion that has been informed by their own personal experiences, but no one, it seems, really has an answer.

Inspired by Michael Chabon’s recent essay, I investigated what he and a few other notable writers have said about having (or not having) children, and the below collection represents more or less the full spectrum: from Cyril Connolly’s horror of the impact of the domestic on the artist to those who go so far as to directly credit their children with their literary success.

So, without further ado: if you’re a writer, should you have kids?

Cyril Connolly: No

Cyril Connolly: No

Well, of course we’ll have to start with Connolly, whose bitter declaration about writers and prams is often repeated. Here is the full passage, from Enemies of Promise:

In general it may be assumed that a writer who is not prepared to be lonely in his youth must if he is to succeed face loneliness in his middle age. The hotel bedroom awaits him. If, as Dr. Johnson said, a man who is not married is only half a man, so a man who is very much married is only half a writer. Marriage can succeed for an artist only where there is enough money to save him from taking on uncongenial work and a wife who is intelligent and unselfish enough to understand and respect the working of the unfriendly cycle of the creative imagination. She will know at what point domestic happiness begins to cloy, where love, tidiness, rent, rates, clothes, entertaining and rings at the doorbell should stop and will recognize that there is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hall.

No children, then, and no spouses either.

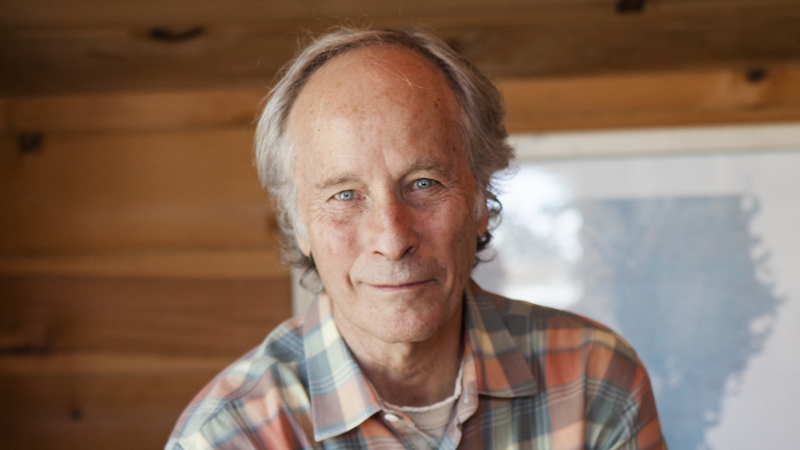

Richard Ford: No

Richard Ford: No

In 2010, Ford wrote a list of ten rules for writing fiction for The Guardian. Note #2:

1. Marry somebody you love and who thinks you being a writer’s a good idea.

2. Don’t have children.

3. Don’t read your reviews.

4. Don’t write reviews. (Your judgment’s always tainted.)

5. Don’t have arguments with your wife in the morning, or late at night.

6. Don’t drink and write at the same time.

7. Don’t write letters to the editor. (No one cares.)

8. Don’t wish ill on your colleagues.

9. Try to think of others’ good luck as encouragement to yourself.

10. Don’t take any shit if you can possibly help it.

In a 2012 interview with The New York Times, he addressed the issue more directly:

You don’t have any children. In fact, you once said, “I hate children.”

No, no, no. I don’t hate children. My wife and I just didn’t think we would be good parents, and also by the time we got married in 1968, we were pretty nose-down toward what we wanted to do, and having a child was going to be an excuse to fail.

So you think a person has to choose to be either a great novelist or a parent?

I can only speak about myself, not for anybody else. I’m not smart enough to do that kind of multitasking. I would always be wishing I were doing the other thing and not doing either one well.

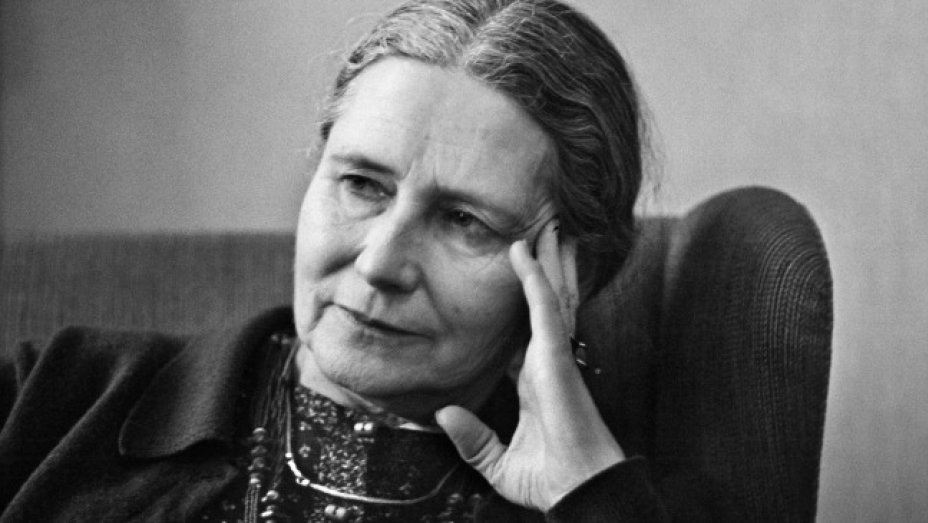

Doris Lessing: No

Doris Lessing: No

“No one can write with a child around,” Lessing said in a 2008 interview. “It’s no good. You just get cross.” Of leaving her two children, as she famously did, in Southern Rhodesia and returning to England, she said: “For a long time I felt I had done a very brave thing. There is nothing more boring for an intelligent woman than to spend endless amounts of time with small children. I felt I wasn’t the best person to bring them up. I would have ended up an alcoholic or a frustrated intellectual like my mother.”

Geoff Dyer: No, but not because you’re a writer

Geoff Dyer: No, but not because you’re a writer

From his essay in Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision Not to Have Kids, edited by Megan Daum:

If you can’t handle the emptiness of life, fine: have kids, fill the void. But some of us are quite happy in the void, thank you, and have no desire to have it filled. Let’s be clear on this score. I’m not claiming that I don’t need to have kids because my so-called work is fulfilling and gives my life meaning. To be honest, I’m slightly suspicious of the idea of an anthology of writers writing about not having kids. Obviously any anthology of writing is, by definition, full of stuff by writers, but if this is a club whose members feel they have had to sacrifice the joys of family life for the higher vocation and fulfillment of writing, then I don’t want to be part of it. Any exultation of the writing life is as abhorrent to me as the exultation of family life. Writing just passes the time and, like any kind of work, brings in money.

Rachel Cusk: Maybe

Rachel Cusk: Maybe

Cusk unpacked her ambivalence about motherhood in her memoir A Life’s Work: On Becoming a Mother—which she took a lot of pretty sexist flak for in the press at the time:

To be a mother I must leave the telephone unanswered, work undone, arrangements unmet. To be myself I must let the baby cry, must forestall her hunger or leave her for evenings out, must forget her in order to think about other things. To succeed in being one means to fail at being the other. . . I never feel myself to have progressed beyond this division. I merely learn to legislate for two states, and to secure the border between them. At first, though, I am driven to work at the newer of the two skills, which is motherhood; and it is with a shock that I see, like a plummeting stock market, the resulting plunge in my own significance.

Jane Smiley: Sure

Jane Smiley: Sure

In a 2015 interview with Nicole Rudick for the Paris Review, Smiley explains:

When I was younger, when I was starting out, I was distracted by the kids. I had my two hours of allotted time while they were with the babysitter, and most of the time I tried to make it productive. But I also recognized that maybe it wasn’t going to be productive, so I’d take a nap instead. But having the kids as a distraction, having to do my time and then go pick the kids up at school or go to the grocery store or whatever—that was always good because something might happen out on the street that would be an idea. . . . One of the ones that sticks in my mind was when I went to the daycare and saw all the four-year-olds crossing the street in front of the church in two lines. My inner mom says, Oh my God, what if a car comes screaming down the street right over the kids? And my inner author says, Wow, that’s an idea. So my inner author was always sucking dry the inner mom or the inner girlfriend or the inner life or the inner horse owner and trying to make something of whatever that thought might be.

Alice Walker: Yes, but only one

Alice Walker: Yes, but only one

In The Atlantic, Lauren Sandler wrote a controversial essay entitled “The Secret to Being Both a Successful Writer and a Mother: Have Just One Kid.” You can guess what it suggests. In the essay, she reports: “Someone once asked Alice Walker if women (well, female artists) should have children. She replied, “They should have children—assuming this is of interest to them—but only one.” Why? “Because with one you can move,” she said. “With more than one you’re a sitting duck.””

Zadie Smith: Yes, and more than one if you want

Zadie Smith: Yes, and more than one if you want

Zadie Smith was not impressed by Sandler’s essay. In the comments (now deleted but reported in The Guardian), she wrote:

I have two children. Dickens had 10—I think Tolstoy did, too. Did anyone for one moment worry that those men were becoming too fatherish to be writeresque? Does the fact that Heidi Julavits, Nikita Lalwani, Nicole Krauss, Jhumpa Lahiri, Vendela Vida, Curtis Sittenfeld, Marilynne Robinson, Toni Morrison and so on and so forth (I could really go on all day with that list) have multiple children make them lesser writers? Are four children a problem for the writer Michael Chabon—or just for his wife, the writer Ayelet Waldman?

. . .

We need decent public daycare services, partners who do their share, affordable childcare and/or a supportive community of friends and family. As for the issue of singles v multiples v none at all, each to their own! But as the parent of multiples I can assure Ms Sandler that two kids entertaining each other in one room gives their mother in another room a surprising amount of free time she would not have otherwise.

Hari Kunzru: Yes

Hari Kunzru: Yes

In a 2013 essay in The Guardian, Kunzru wrote:

Every young writer remembers Cyril Connolly’s doom-laden pronouncement in Enemies of Promise that “there is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hall.” There is an economic basis to this—I’m not sure I’d be a working novelist if I’d had a family at 25—but Connolly also speaks out of a long and toxic tradition that sets art (ethereal, otherworldly, all unravished brides of quietness and unreal cities) against the mundane domestic world. It’s particularly toxic for men, since it suggests that in order to be true to your work, to have a chance to do it well, you must betray, or at least skimp on the commitments you’ve made to your partner and your children. It’s an idea that has given a license to generations of male writers to behave—not to put too fine a point on it—like assholes. Moreover, it’s blind to the idea that being a father, with its intense, earth-shattering experience of love, could ever provide material for art. That would be (say it in hushed tones) rather reminiscent of women’s writing. You know, that tawdry kitchen-sink business, all self-sacrifice, dirty nappies and wishing one had a room of one’s own.

I should say at this point that, like a fool, I married, not a worshipful, doe-eyed helpmeet or an heiress who could subsidise my forays into the avant garde, but another writer, whose work is as important to her as mine is to me. Much as my inner patriarch would love to set up a domestic situation where the children and servants tip-toe past my study door as I smoke my pipe and channel the muse, that’s not how it will be. Our intention (we are only six months into this) is to bring our son up as equal partners. Since we both work at home, we’re already finding that even when one of us is “officially” writing, there’s a tendency for the whole sleep-deprived family to end up on the bed, laughing and pretending to eat each others’ toes. This is clearly not a situation that can last. Deadlines loom. Bills must be paid.

. . .

There are few models for the novelist as hands-on father—JG Ballard is one, the widower writing his dystopias in the afternoons before the school run. On the other hand, there’s a sizeable canon of monster-fathers, like William Faulkner, who told his 12-year-old daughter—as she begged him to give up drinking—that “no one remembers Shakespeare’s children”. Knausgaard remembers his, even when he’d rather forget them. I hope I always remember mine. I don’t believe it will make me a lesser writer.

Karl Ove Knausgaard: Yes

Karl Ove Knausgaard: Yes

Speaking of Knausgaard, as he told the Financial Times in 2014: “When I started to write I thought I had to be isolated. I went to lighthouses in the sea, and uninhabited islands. But then I had children and I realised I had to do it at home. I’ve never written as well as I have since having children.”

Lily King: Yes

Lily King: Yes

During a 2015 conversation on “Mothers & Writing” at the Cambridge Public Library, King remembered:

Looking back at when I was single and childless, there was a lot of wasted time. It helped me to have a concentrated amount of time that I knew was going to expire. My first novel took eight years—much longer than my novels since then. . . Once I had kids, my sense of self was no longer completely defined by my success or failure as a writer. It’s given me confidence as a writer to try things, and worry less about failing.

Michael Chabon: Yes

Michael Chabon: Yes

In Chabon’s recent GQ essay, “Are Kids the Enemy of Writing?,” he reports an early-career meeting with an unnamed “great man” (who is probably Richard Ford) who warned him not to have children. “Don’t have children,” he said. “That’s it. Do not. That is the whole of the law. . . “You can write great books . . . Or you can have kids. It’s up to you.” Chabon reports:

If I had followed the great man’s advice and never burdened myself with the gift of my children, or if I had never written any novels at all, in the long run the result would have been the same as the result will be for me here, having made the choice I made: I will die; and the world in its violence and serenity will roll on, through the endless indifference of space, and it will take only 100 of its circuits around the sun to turn the six of us, who loved each other, to dust, and consign to oblivion all but a scant few of the thousands upon thousands of novels and short stories written and published during our lifetimes. If none of my books turns out to be among that bright remnant because I allowed my children to steal my time, narrow my compass, and curtail my freedom, I’m all right with that. Once they’re written, my books, unlike my children, hold no wonder for me; no mystery resides in them. Unlike my children, my books are cruelly unforgiving of my weaknesses, failings, and flaws of character. Most of all, my books, unlike my children, do not love me back. Anyway, if, 100 years hence, those books lie moldering and forgotten, I’ll never know. That’s the problem, in the end, with putting all your chips on posterity: You never stick around long enough to enjoy it.

Lev Grossman: Yes

Lev Grossman: Yes

In his essay “Daughter Pressure,” published in When I First Held You: 22 Acclaimed Writers Talk About the Triumphs, Challenges, and Transformative Experience of Fatherhood, and republished by Slate, Grossman writes:

For the first time in life, I felt like it mattered what I did, and who I was. It was all well and good for me to fuck around and write mediocre fiction when I was just some asshole. But I wasn’t just any asshole anymore: I was Lily’s father. I could let myself down all I wanted, all day long, year in and year out, but I was damned if I was going to let her down. Any time I wrote a sentence that was less than true I could feel her looking over my shoulder and shaking her head, slowly and sadly: Come on, Daddy. We both know that’s crap. Having a child didn’t make me wise or mature, but it did make me realize how unwise and immature I was. It was a start.

I’ve started to think that the business of making new people is actually pretty important—important enough to go on a life plan, even. Because otherwise where would new people come from? My only regret is that my parents never taught me how to be a father, so my daughter had to teach me instead. It’s a lot to ask from a little girl. Fortunately, my little girl is tough as nails.

Not only that, she taught me how to be a writer. It took me five years to finish the book I started after she was born, writing during nights and weekends and naptimes, but I did finish it, and eventually it was published. It became a best-seller, and the sequel was a best-seller too. In a way, having children did screw up my life plan, well and good. Probably I would have written a hell of a lot more if I’d never had kids. But I would have been miserable doing it, and I’m pretty sure that what I wrote wouldn’t have been worth a damn. It wasn’t that I’d finally, at long last, found my voice. It’s that Lily had found it for me.

Helen Dunmore: Yes

Helen Dunmore: Yes

Located in Dumore’s own ten rules for writing fiction, as told to The Guardian:

8. If you fear that taking care of your children and household will damage your writing, think of J. G. Ballard.

Ballard, of course, had three children and raised them as a single father; in his lifetime he published 19 novels and 17 short story collections (and that’s without counting Collected and Best Of volumes). Not a bad model.