How Colonialism and Patriarchy Create Enduring Misery for Native American Women

Sofia Ali-Khan on the Brutal Legacy of the United States’s Westward Expansion

In the summer of 1994, I met up with Aaron at a place called the Social Justice Design Institute (SJDI), a month-long summer camp for progressive artists and musicians inclined toward political activism. SJDI was led by the music professor and composer Herbert Brun, some of his former students, and other people in the orbit of the campus on which he taught, meant to inspire student activists to “imagine and design a [society] they would prefer” and then to express those ideals through theater, art, and music. I applied for a scholarship to cover tuition as well as room and board and got it. I just had to find a way to get to Sioux Falls, South Dakota, where that summer’s camp was being held in a large Victorian house, on loan from a friend of one of the organizers.

When I boarded a Greyhound bus to travel more than a thousand miles from Flagstaff, Arizona, to SJDI in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, I was tan from the Arizona sun, with thick black hair falling straight to my chin. Dressed in simple cotton pants and T-shirt, and with a green hiking pack, I was the kind of scrawny that comes from traveling on a shoestring budget, just over a hundred pounds and barely five foot two. I had very little cash, half of it in quarters for payphones wherever I could find them.

During a six-hour stop at the bus depot in Jackson County, Missouri (named for President Andrew Jackson, the architect of “Indian removal”), on the border with Kansas, as the summer sun set, I was terrified. The passengers were mostly male and I felt suddenly like I couldn’t make enough space around myself to avoid their attention. As the clock inched closer to our departure time for the last leg, 12:50 am, their leers became more suggestive, more pronounced. I avoided the bathrooms and dug a heavy steel pocketknife out of my bag to wear on a string around my neck.

I’d thought it was just because I was a young woman. I couldn’t have avoided it: The bus was the cheapest way to get to my next destination; even today, a bus ticket from Flagstaff to Sioux Falls costs less than a hundred dollars. I didn’t understand that I was experiencing the magnified danger of being a Native-looking woman traveling alone through what some people call “fly-over country.” I had not yet learned about the devastating numbers of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) in America. My two-day journey would take me through a triangle of land between three of the region’s most densely populated Native communities. Within this triangle, I was not light enough to pass; I was raced as “Indian.”

I didn’t understand that I was experiencing the magnified danger of being a Native-looking woman traveling alone through what some people call “fly-over country.”

The irony is that I am, ethnically, the kind of Indian early European settlers in the Americas thought they were encountering—the kind from what they called India, before it also became Pakistan and Bangladesh. And in an even further irony, the India of Asia before the British arrived was not India at all, but more than a dozen separate kingdoms, robbed of a future in which their distinct languages, politics, and cultures could coalesce into nation-states. In some sense, “Indian,” whether in America or in Asia, is a figment of the colonial imagination; it is the name of a lens through which White colonizers see us, and, as a result, how we sometimes come to see ourselves. In both places, it is arguably a synonym for savage.

Maybe it stands for the savagery ascribed to us, or maybe it identifies us as the objects of savagery. The truth is that none of us is Indian. Importantly, we are separate people, diverse from one another, whether native to South Asia or to the Americas, with many complex cultures and faiths that endured for thousands of years prior to European colonization. Our groups have names and languages, and ways of being that are often derived from, and tied intimately to, a specific ecology. These are obscured in a colonial context, where we are renamed by whatever colonial authority there is. The colonized everywhere are assessed only for whatever value, labor, or service we might provide, then assimilated or destroyed.

As I looked at the history of Sioux Falls, I began to better understand my experience on that bus from Flagstaff. My route that summer had taken me through five of the ten states identified by the Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI)’s 2017 report as those with the most reported incidence of MMIWG. I’d traveled through Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and along the border of Nebraska and Minnesota, the locations of 40 percent of cases cited.

The National Institute of Justice (NIJ) has found that Native women experience the highest rates of rape and sexual violence of all racial categories in the United States and, in some counties, are murdered at a rate more than ten times the national average. High rates of poverty and homelessness contribute to high rates of sexual exploitation and trafficking among Native women.

All of these, the NIJ report suggests, are linked to the “torture and trauma” of colonization, including dislocation, dispossession, persecution, and abusive residential schools. On reservations, the issue of MMIWG intersects with issues of environment justice. A growing body of reports, studies, and congressional testimony suggest that oil pipelines and the “man camps” that house their workers, often located on or near reservations, increase rates of violence against Native women and girls.

My two-day journey would take me through a triangle of land between three of the region’s most densely populated Native communities. Within this triangle, I was not light enough to pass; I was raced as “Indian.”

In January of 2021, the U.S. Department of Justice Journal of Federal Law and Practice dedicated an issue to missing and murdered indigenous persons. It contains an article drawing on the National Crime Victim Survey, the National Violence Against Women Survey, and the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey to provide the most comprehensive data on violence against women and girls over age twelve identifying as American Indian or Alaskan Native.

These respondents had the highest lifetime prevalence rates of any racial category for physical assault at 61.4 percent, stalking at 17 percent, and rape at 34.1 percent. Combining rape and physical assault, two-thirds of respondents experienced at least one violent incident in their lifetime. Respondents also experienced much higher rates of intimate partner violence than their white counterparts, 38.2 percent compared to 29.3 percent. Combining rape, physical assault, stalking, and intimate partner violence, 39.8 percent of respondents experienced some form of these in the preceding year. Violence against Native respondents, particularly sexual violence, was broadly interracial; 94 percent of perpetrators of rape or sexual assault were identified as White or Black.

There was little hope of a comprehensive investigation of the problem of MMIWG in the United States until the recent appointment of the former congresswoman and member of the Laguna Pueblo nation Deb Haaland as U.S. Secretary of the Interior. Lacking a powerful champion of the issue, advocates previously encountered a persistent lack of governmental funding and support. In addition, jurisdictional rules and lack of proper race reporting in law enforcement have compromised prosecution and data collection on reservations and in urban settings.

Native governments retain sole jurisdiction in crimes on reservation lands only when both the victim and the perpetrator are Native, which is only a small minority of cases involving MMIWG. The federal government retains jurisdiction over the rest and often declines to prosecute, leaving many crime victims in Native communities without recourse. In addition, the same UIHI study cited above found that many municipal law enforcement agencies’ computer data systems lack a way to accurately designate the race of Native victims, and that these agencies frequently fail to provide the information they do have to advocates.

In April of 2021, after only two weeks in office, Secretary Deb Haaland announced a new Missing and Murdered Unit (MMU) within the Bureau of Indian Affairs to investigate the extreme and ongoing violence against Native people in America, particularly violence against Native women and girls. After a federal inquiry into MMIWG in Canada, that government deemed the matter a genocide. The crisis of MMIWG in the United States is believed to be similar in nature and magnitude.

The colonized everywhere are assessed only for whatever value, labor, or service we might provide, then assimilated or destroyed.

Like Native women, Native children have been taken from their communities at an alarming rate. In the era after their forced confinement in residential schools, Native children have continued to be disproportionately represented in many state child welfare systems, which then frequently place them with non-Native families. In the 1960s, the Association on American Indian Affairs (AAIA) found that between 25 and 35 percent of Native children “had been placed in foster care, adoptive homes, or other institutions—and 90 percent of those kids went to White families.”

This problem has a nefarious precedent. From 1958 through 1967, the federal government pursued the forced assimilation of poor Native children from the western part of the United States by placing them with non-Native East Coast families through the Indian Adoption Project. In 1978, as Native peoples developed incremental political power, and as the disastrous outcomes of such programs became clear, Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), legislation aimed at keeping Native children in Native communities.

But ICWA has not resolved the disproportionate representation of Native children in South Dakota’s child welfare system. In 2015, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed a case on behalf of the “Redbud and Oglala Sioux” in federal court, alleging that the defendants, all in their official capacities within the state child welfare system, had implemented policies and procedures in violation of ICWA and the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In the process of discovery, the ACLU found that Native parental rights in South Dakota were often terminated in hearings that lasted no more than sixty seconds, that parents were denied the ability to challenge the adequacy of those hearings, and that the state won 100 percent of hearings over four years. Of the more than eight hundred children taken from Redbud and Oglala communities between 2010 and 2014, most were placed with non-Native families. The Redbud and Oglala won declaratory and injunctive relief in federal court, with the court ordering changes to state child welfare procedures.

Although the ACLU reported that some important changes had been implemented in accordance with the order, an appeals court later overturned the decision, ruling that the case should not have been heard in federal court at all. The Supreme Court declined review. In 2017, the ACLU cited South Dakota Department of Social Services statistics that showed Indigenous children were still “11 times more likely to be placed in foster care than a White child in South Dakota.”

Similarly, a 2017 report by the National Indian Child Welfare Association found that while Native children account for 12.9 percent of the children in South Dakota, they are 47.9 percent of children in the state’s child welfare system. Advocates argue that the disproportionate removal of Native children from their communities is driven by racist ideas about the capacity of Native families to care for their children and the misinterpretation of poverty as neglect or abuse. Opponents have argued that the child welfare standard of the “best interests of the child” should not be compromised by adherence to ICWA, and that removing children from Native communities is necessary where there are limited Native placements for at-risk children.

In early 2020, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals reheard an argument in the case of Brackeen v. Bernhart alleging that ICWA, because of the preference it creates for keeping Native children with their Native communities, is unconstitutional. The plaintiffs include the three states of Texas, Indiana, and Louisiana, along with seven non-Native individuals seeking to adopt Native children. Plaintiffs argued that procedural obstacles imposed by ICWA were unconstitutionally race-based, and that ICWA both exceeded permissible federal authority and also impermissibly delegated federal powers to tribes.

In 2021, the United States Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals published a 325-page en banc opinion in the case, affirming the overall constitutionality of ICWA but eliminating provisions of the law that require specific acts, testimony, and record-keeping before placing Native children with non-Native families. The appeals deadlocked on at least one other key provision of ICWA, which requires that preference be given to placing Native children with extended family, members of the same Native community, or foster homes approved by that Native community. All parties petitioned for U.S. Supreme Court review of the appeals court decision on September 3, 2021.

__________________________________

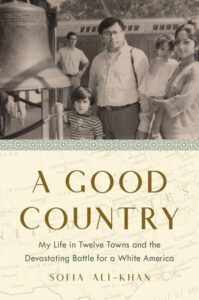

Excerpted from A Good Country: My Life in Twelve Towns and the Devastating Battle for a White America by Sofia Ali-Khan. Copyright © 2022. Available from Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Sofia Ali-Khan

Sofia Ali-Khan is a writer and an accomplished public-interest attorney. She has worked for Community Legal Services of Philadelphia, Prairie State Legal Services in Illinois, and the American Bar Association. She became a national leader on the right to language access and also practiced in the areas of welfare law, Medicaid access, immigration, and community economic development. She was a founding board member and activist with the Philadelphia chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR). A second-generation Pakistani American born and raised in the United States, Ali-Khan now lives in Ontario, Canada, with her family.