How Audre Lorde’s Genre-Blurring Zami Spoke My Truth Into Existence

Jamika Ajalon on Biomythography, Friendships, and Queer Identity

I think it’s the one photo that might have survived the bonfire. The one my roommate took that time she snuck in, freezing into eternity the moment my lover and I lay intertwined in postcoital glow. She laughed when the click of her camera caused us to look up, startled and slightly embarrassed. It had been a particularly passionate lovemaking session; our shouted pleasures shook the windows and reverberated out into the summer air glazing the streets of Washington Heights, New York. My roommate at the time said that the photo was to remind us of the love we share during the rough times to come.

This romance, similar to a few special others, would come to mark a significant chapter in my life. However, what I would come to understand more deeply, as time went on, was that my roommate was documenting a moment that held many layers of rare archive; it was about more than simply our love story. She was documenting a historical happening, a portrait that spoke a truth about a specific time in history. The woman who took the picture was Audre Lorde’s daughter, and the room I was renting had been her mother’s, still full of the beads Lorde would fashion into necklaces and bracelets when she was in town. I’d moved in not so long after her passing. My nipple piercing, which I’d gotten days after Lorde’s death in symbolic dedication to doing the work, was still healing.

Being women together was not enough. We were different.–Audre Lorde, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name

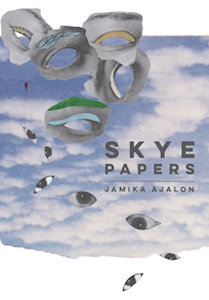

When I picked up Audre Lorde’s “biomythography,” Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, for the first time, I was already living the narrative that would later be fodder for the first drafts of Skye Papers, a novel that I wouldn’t begin writing until I had been based in Europe for some years. I’d left the States, to study, for love, but the driving primary impulse that made me stay was to do the work; that is, to find and somehow document what I would have then called “other freaks like me” outside of the Amerikan bubble. Folks who, as Lorde put it in Zami, “felt more comfortable at the extremes.”

In 1990s popular media, the era in which Skye Papers is framed, there were really no representations of the scene I moved in, one which was neither strictly queer nor Lisa Bonet bohemian. We were an eclectic crew; many of us refused to be fixed to this or that definition of who we were, well before Kimberlé Crenshaw’s theories on intersectionality broke through into our scholarly curriculums and popular discourse.

Some of us even struggled with the moniker “African American,” not only because it seemed to exclude nuances of our identity, but because many of these self-described “African Americans” excluded us. We were too queer, too light, or too out there to be truly black. The narratives I wanted to represent at that time were, to most folks, so unlikely as to be scarcely possible. As impossible as the existence of black Beat poets, the likes of Bob Kaufman. Even though the finger-snapping Beat Generation too-cool-for-school lingo sounded a lot like the way jazz musicians would rap to each other uptown, history continues to insist that it was invented by cool clever white men like Elvis. And you would be hard-pressed to hear about James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room during Black History Month.

Being a punky, genderfluid, brown skin queer in the 1990s did not compute in the minds of most, including some of our melanated brothers and sisters. However, we did exist as agents to our own being, a part of the cultural tapestry, setting trends that destabilized, then expanded ideas around so-called norms. On television—even within the rising genre of counterculture magazines, documentaries, and reality TV shows that fed mainstream media—our existence was subsumed into a commodity that had nothing to do with us. Perhaps who we really were was far too mercurial for prime time. It certainly slipped through the cracks between the niches fixed into place to support the so-called “dominant narrative.”

Zami was part of a body of work that profoundly informed the genre-blurring methods I would employ to speak my, and our, stories into being. Jewelle Gomez explained it this way when speaking about Lorde’s influence on her work:

ZAMI however imagines our lives, not those of gods, priestesses or animals, as both magic and epic, expanding the reader’s vision of the past, present, and future… along with my affinity for stories embodying “otherness” in the extreme… [it] enabled me to imagine my fiction within the legacy of US storytelling. The less I tried to fit into the traditional picture (white, American, heterosexual realism), the easier it was to see myself and write the words that would take their place in our culture. (Gomez, “Lesbian Self-Writing: The Embodiment of Experience,” Journal of Lesbian Studies Volume 4, Number 4)

With Zami, Lorde both named and gave a blueprint for a way of writing our existence, our truth. The idea of mythologizing one’s life, one’s lived experience, burst all kinds of doors wide open for me artistically, even those I was yet to discover. Certainly, without Zami, Skye Papers would have had no runway to take off from.

Being gay girls together was not enough. We were different.

Being black together was not enough. We were different.

–Audre Lorde, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name

One hot summer back at the apartment in Washington Heights, sweating among Audre Lorde’s spiraling cones of twine and colorful wooden beads, a 16mm camera hummed, filming me as “Lotto” following a trail of scattered shoes leading to my lover “Lana.” The film, Shades, was based on “Kaleidoscope,” a short story I was revising at the time for the groundbreaking Anchor House anthology of black lesbian writing, Afrekete (ed. McKinley & Delaney). “Kaleidoscope,” a psychedelic adventure and love story, would be, in many ways, a precursor to Skye Papers as well as other future interdisciplinary creations. I was already experimenting with mixing different genres of writing through a surreal, often futuristic lens; I was also integrating different artistic mediums as an extension of my pen.

With Zami, Lorde both named and gave a blueprint for a way of writing our existence, our truth.

Both Shades and “Kaleidoscope” were poetic retellings of real events and issues that my relationships at that time raised. Was it told through a web of lies and fantastic fabrications? Yes, but simultaneously, as with Skye Papers, it was a conscious mythologizing of real lived experiences during an era that brought the 20th century to a close, when queer people of color were expanding, integrating, and creating a transatlantic network of artists, lovers, poets, and thinkers connecting beyond borders—a scene that was new and simultaneously as old as any story echoing our presence and influence over the centuries, in supposedly unlikely places and spaces.

We were different. Being black women together wasn’t enough we were different.

Being Black dykes together was not enough. We were different.

–Audre Lorde, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name

Audre Lorde described “Zami” as a Carriacou name for women who work together as friends and lovers. These alliances, even the ones forged only to be lost under the fickle and sometimes cruel winds of time, line the paths of our survival up to this very moment. These friendships, whether short-lived or for a lifetime, are not only an inextricable part of who I am today, but also a large part of the reason that I am today.

I picture myself, one day, looking through some forgotten, stored-away box and finding that photo that my roommate took of me and the first woman I ever wanted to marry. Most of the evidence of that love story I would impulsively torch just after our breakup (oh, the drama!), along with the locs I had been sporting when we first met.

Happily, even under the flames of my rage, I didn’t burn everything. I knew, somewhere deep down, that what that photo of us represented was a thousand times more expansive than our fleeting love story; it belonged to a legacy much older than us, one that, long after we left our bodies behind, would embrace us into the beyond.

__________________________________

Skye Papers is available from The Feminist Press. Copyright © 2021 by Jamika Ajalon.

Jamika Ajalon

Jamika Ajalon is a prolific author and interdisciplinary artist who works with different mediums independently, but also in multiple fusions—incorporating written and spoken text, sound/music, and visuals. Her poems, stories, and essays have been published in various publications internationally. She currently writes a regular column for Itchy Silk magazine, “queer plume: the fugitive diaries.” She has performed her audiovisual anti-lectures / sonic slam and exhibited across the globe, and has a BA in Film/Video and an MA in Communications in Culture and Society, from Goldsmiths University.