How a 1970s Literary Travelogue Can Transform Us All

David Santos Donaldson on Tété-Michel Kpomassie’s An African in Greenland

An African in Greenland, Tété-Michel Kpomassie’s 1970s literary travelogue, was reissued by Penguin Modern Classics this February in English with a brand-new title, Michel the Giant: An African in Greenland. Although the new title refers to how Inuit locals first saw the towering Black man (the first to venture to Greenland), it is also an apt description of the man in general. Tété-Michel’s extraordinary vision and destiny seem larger than life.

In a recent Guardian interview, he shared that after four decades in France, at 81, he plans to return to his “spiritual home,” to live out his last years communing with spirits in the icebergs of Greenland. He is leaving behind his entire family to follow his “destiny.” Tété-Michel’s strange, outsized journey is unlike any other, and certainly not like mine. But this giant’s remarkable book, transformed me, both as a Black man and a writer—and I believe it can transform us all.

All of us in the Western World exist under the cloud of Whiteness, whether or not we’re aware of it. The unconscious default preference for Eurocentric values and characteristics is pervasive; insidious. It’s a particularly dangerous default for a Black person. Internalizing such a worldview minimizes, if not dehumanizes, oneself. French West Indian psychiatrist Frantz Fanon called this condition “internalizing the oppressor.” It’s a thorny matter to contend with. And yet, with his seemingly apolitical travel memoir (and, indeed, with his very life), Tété-Michel provides a challenge to this condition, a kind of credo: it takes becoming a giant to rise above the clouds, out of the shadows, and to realize one’s true destiny.

The way I discovered An African in Greenland seems uncanny—if not predestined. I had just finished the first draft of my novel, Greenland, in which there’s a historical figure, Mohammed El Adl—the first lover of the English novelist, E.M. Forster. El Adl was a Black Egyptian tram conductor Forster met in Alexandria during World War I. As I began to imagine Mohammed’s mindset, I was visited by one of those rare ideas that seemed to spring from the ether: What if Mohammed was obsessed with the idea of escaping Africa to live in the Artic with the Inuit? What if he dreamed of building his own igloo—and if by doing so, it made him feel truly fit for survival? After giving my draft to a friend, he called me on the phone asking if I had based my Greenland idea on the man from Togo. I had no idea what he meant.

And that’s when he told me about An African in Greenland. I was floored. How could I have imagined such a farfetched idea, only to find someone had actually realized this astonishing aspiration? As soon as I could, I found a copy of Tété-Michel’s book and was rapt by his extraordinary tale. I also couldn’t believe my luck. At the exact right moment, this singular book had fallen into my lap. It was exactly what I needed to help me complete my own Greenland. It had to be fate.

Tété-Michel’s real-life story also reads like something fateful and fantastical. Raised in a traditional Togolese village, at the age of 16, he was saved from snake poison by a snake cult shaman. To show his gratitude, Tété-Michel’s father offered up his son to live permanently with the shaman’s cult in the jungle. But Tété-Michel, deadly afraid of serpents, decided to run away from home and follow his childhood dream—one that had become an obsession throughout his youth—to go to Greenland and live with the Inuit.

As a child, Tété-Michel found a book in the local library, The Eskimos from Greenland to Alaska, by Robert Gessain. He learned that in Greenland it was customary that parents never forced children into anything. As the years passed, young Tété-Michel’s obsession never relented, and it fueled an incredible journey that took him from Africa to Europe and eventually to his destiny, Greenland.

As the years passed, young Tété-Michel’s obsession never relented, and it fueled an incredible journey that took him from Africa to Europe and eventually to his destiny, Greenland.

An African in Greenland also reads like the work of an accomplished novelist. We are transported through Tété-Michel’s various worlds with such skill that we feel we are there with him—in the snake shaman’s jungle den; pitching back and forth on the freezing, turbulent ship’s passage from Denmark to Greenland; eating raw whale fat with Inuit families living in squalor; sleeping with Greenlandic women while their husbands or fathers nonchalantly condone the couplings; or trekking in the most Northern parts of world with huskie sleds; and even, on a rare occasion, following suggestions to eat raw huskie meat. All of this is recounted in keenly observed detail, and executed with such a level of specificity, I am reminded of the ultra-realism of Tolstoy—another giant among men.

Tété-Michel’s experiences, from Togo to Greenland, are all seen through the lens of an African raised exclusively in a traditional Togolese village—not in a westernized town. This unique perspective is what makes his work unparalleled. Most travelogues from its era reek of patronizing Eurocentrism. An African in Greenland seems of today—a time when the literary establishment is beginning to embrace perspectives that reverse the White Gaze.

Yet, Tété-Michel is doing even more than reversing the gaze. He views Greenland and its people, outside of the paradigm of Whiteness altogether. The way in which he assimilates to the local customs and their animistic worship of sea gods and ancestors, brings no patronizing exoticism. He tells us of the Greenlandic spiritual “magical reality” as factual.

Having the remarkable quality of allowing us to enter into this rare space where Whiteness is not centered, Tété-Michel frees us to look at the world anew; and to be free from the parameters within which we normally define ourselves. It reminds me of how Toni Morrison spoke of her own desire to write of the Black experience without any reference to Whiteness, and how she had to look to African writers, such as Chinua Achebe, for such a model.

Whiteness is not centered, Tété-Michel frees us to look at the world anew; and to be free from the parameters within which we normally define ourselves.

When I first read Tété-Michel’s account, there was a moment when I became conscious there was no European observer looking over his shoulder or requiring explanations—that Tété-Michel was talking to me as if I, too, would accept the Greenlandic reality free of the White Gaze. And then, somehow, I found myself remembering the time I burst into tears at a performance of a play in a Brooklyn theater:

In Jackie Sibblies Drury’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Fairview, there is a startling finale in which all white people in the audience are asked up on stage, as the Black cast, along with the non-white audience members, look on from the house. As we gazed up at the white people nervously fidgeting and squinting under the blinding stage lights, we realized they couldn’t see us. A young Black actress comments about the lights: “They’re bright aren’t they? / Should I tell them [the white people] the lights are there to help people see them, / not to help them see anything?” She goes on to ask how we non-white people could tell our own stories outside of the White Gaze.

She begins the old familiar narratives: we are either trying to prove we’re just as good; or fighting to be recognized as human; or fighting to get away from Whiteness. But she stops herself before getting out a full sentence of each story. “No,” she says. “It’s hard to find the one I’d wanted to tell.” I unexpectedly burst into tears. A deeper, hidden question of mine had finally been articulated, summoned to the surface: What would my story be without Whiteness?

Tété-Michel—naturally, casually—provides an answer. He recounts being in a Northern Greenlandic village when he was called “nigger” for the first time in his life. It was by an Inuit man who was jealous of Tété-Michel’s luck with local women. Tété-Michel was not fazed by this. He comments, of the offender: he was only “some embittered neurotic trying to work off frustrations that have nothing at all to do with the ‘nigger.’” Being raised outside the context of Whiteness, Tété-Michel has never been defined by this word. He has never internalized the oppressor, and so he isn’t reactive; he can perceive the reality with clarity. He sees the truth of the man who called him “nigger.” Outside the paradigm of Whiteness, Michel the Giant is immune to being wounded by this word.

It is a boon to read a book from a man who moves through the world free of these injuries. It allows us further access to the world of possibilities within his vision. It even emboldens me, as a queer Black author, to strive (in my writing and life) for clarity about the world around me, and not merely to react to it. The destiny of Tété-Michel is perhaps the true destiny for all Black people—and, I dare say, for all artists, even for all of us of the Western World invariably suffering under the dark cloud of Whiteness. We must all strive to become giants.

______________________________

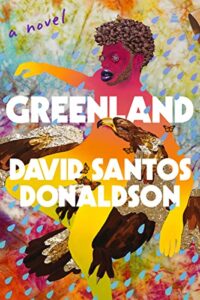

David Santos Donaldson’s Greenland is available now from Amistad.

David Santos Donaldson

David Santos Donaldson was raised in Nassau, Bahamas, and has lived in India, Spain, and the United States. He attended Wesleyan University and the Drama Division of the Juilliard School, and his plays have been commissioned by the Public Theater. He was a finalist for the Urban Stages Emerging Playwright Award and has worked as the Artistic Director for the Dundas Centre for the Performing Arts in Nassau, Bahamas. Donaldson is currently a practicing psychotherapist, and divides his time between Brooklyn, New York, and Seville, Spain. Greenland is his first novel.