Home is a Living Sketchbook: Inside the Artistic Design of Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant

On the Transformation of a Creative Couple's Domestic Space, Structures, and Roles

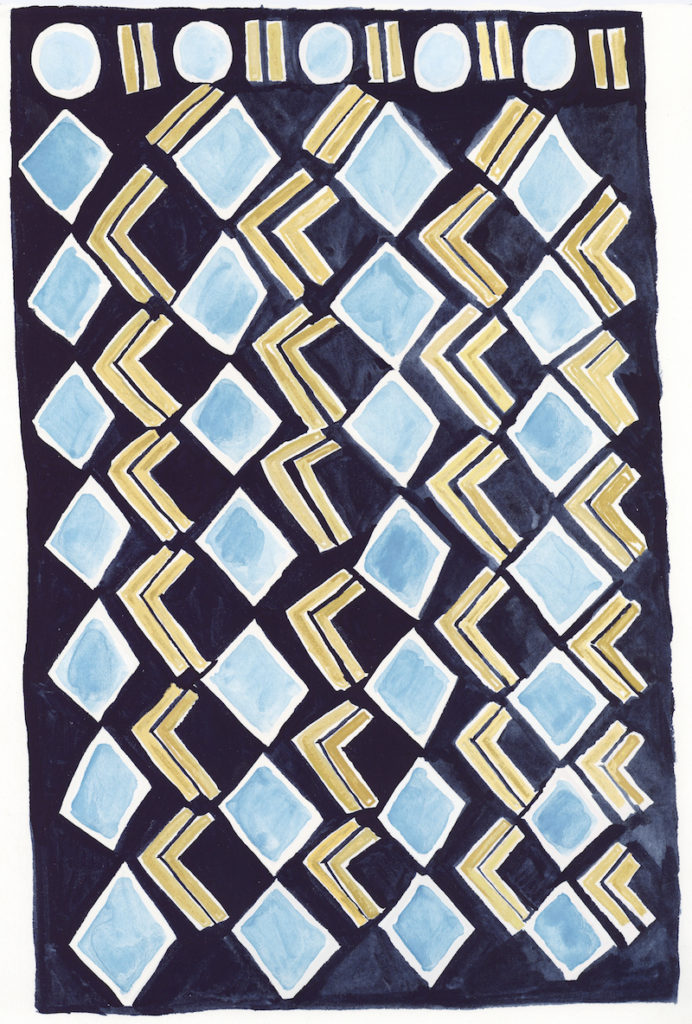

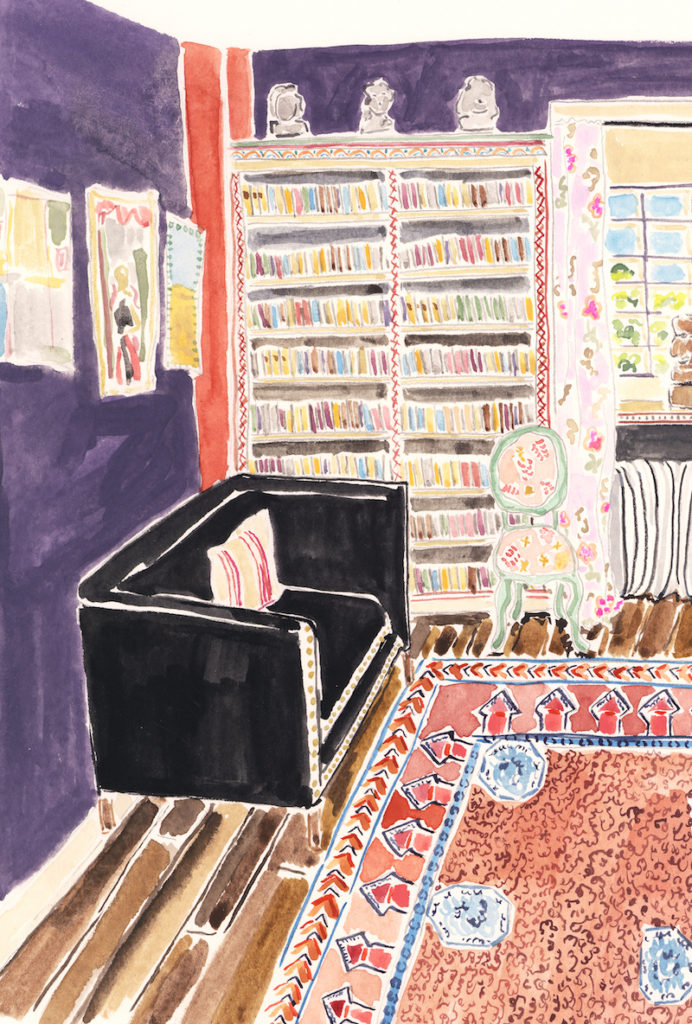

Almost as soon as Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant moved into their home at Charleston, in East Sussex, England, in 1916, they started painting on its surfaces. They painted its walls and mantels, its doors and doorframes, its furniture and cabinet doors and window seats and tabletops. They painted nearly every surface they found, and when there were few new surfaces available, they repainted the surfaces they had already painted. They also designed their own textiles, creating patterns for carpets and upholstery and embroidered canvas. They covered their home with swirls and paisleys and geometric patterns and lush human figures and flowers and painted bowls of painted fish.

The home is a living sketchbook where both artists explored motifs, colors, and patterns, and experimented with artistic form. They created in Charleston not only a home and studio, but also a three-dimensional painting that they could live inside. Bell and Grant moved to Charleston in 1916, in the midst of World War I. Living there allowed Grant to work as a farmer, which was a condition of his conscientious objector status. They wound up living in the house—sometimes as a holiday retreat, and then full time—for decades.

Bell and Grant moved to Charleston in 1916, in the midst of World War I. Living there allowed Grant to work as a farmer, which was a condition of his conscientious objector status. They wound up living in the house—sometimes as a holiday retreat, and then full time—for decades.

The web of family life at Charleston was always a bit complex. Bell was married to the art critic Clive Bell, with whom she had two sons, Julian and Quentin. However, she and Clive seem to have settled into an amicably open marriage by the time she moved to Charleston. At times, Clive came to stay, and he moved into the house on a more permanent basis in 1939, taking on a suite of rooms for his personal use. But though they remained married and friendly, both had other romantic relationships, including the multifaceted connection that developed between Bell and Grant.

When Bell first rented Charleston Farmhouse, Grant moved in along with his serious romantic partner David (Bunny) Garnett. Grant embraced his homosexuality, and he had already had several important romantic relationships with men. Nevertheless, he and Bell had a loving relationship and also a brief interlude of physical connection. In 1918 they had a daughter, Angelica (though they chose to conceal her paternity until she reached adulthood).

Bell and Grant maintained a close friendship long after their physical relationship ended, living platonically together for most of their lives. At Charleston, they enjoyed a harmonious and egalitarian approach to domestic living. And in addition to being longtime friends, they were close and mutually supportive artistic colleagues.

Even before they moved to Charleston, Bell and Grant were propelled by similar rhythms of creative practice and a shared artistic sensibility. In 1913, their friend, the scholar and painter Roger Fry, founded an artists design collective called the Omega Workshops in London, which he asked Bell and Grant to direct. The collective strove to erode traditional distinctions (and hierarchies) between fine art and other forms of artistic design, including interior decoration. Omega artists sought to acknowledge, and even to emphasize, the architectural elements of each space they decorated. Perhaps more than any other artists in this book, Bell and Grant intentionally engaged with philosophies around interior space and decoration.

As directors of Omega, they crafted a philosophical framework that informed their approach to their own home at Charleston. They saw their rigorous practice of painting their home’s surfaces as a part of, and equal to, their artistic expression elsewhere. The paintings at Charleston are fully realized and comprehensive, an undulating spectrum of visual motifs designed to unfold across the entire span of their living space. At Omega they had asserted the idea that decorative arts and interior decoration possessed intrinsic artistic value. In keeping with this philosophy, they transformed Charleston into a house-sized painting, a piece of art in its own right.

Bell and Grant’s approach to painting Charleston reinforces another key tenet of the Omega Workshops’ framework: highlighting the architectural elements already built into the house’s structure. They painted decorative designs and distinct images on Charleston’s moldings and doorframes and fireplace surrounds in order to explore the unique expressive capacity of each feature. They allowed their own artistic vision to complement the existing design elements of the architecture.

The two continued to accept commissions to paint murals and interior spaces long after the Omega Workshops ended, including a series of elaborate murals they completed in Berwick Church, not far from Charleston. Both of them had traveled to Italy and been struck by its frescoes, which had a lasting influence on their own murals and informed their thinking about the aesthetic potentials of painting in the three-dimensional space of an architectural interior. They were also interested in the idea of site-specific art. Charleston, then, served as part of a larger continuum of artistic exploration for both artists.

The visual ideas Bell and Grant explored in their paintings at Charleston connect with many of their core artistic preoccupations. Both artists were interested in how color and form might play out in modern painting. Bell was particularly fascinated by the expressive capacities of simplified form. In both her home and her other work, she frequently explored circular motifs and patterns, and we can see her distinctive colorways and brushstrokes echoed across her interiors and her other paintings.

For his part, Grant returned repeatedly to the human form. He painted two figures above the mantel in the sitting room (which the family called the Garden Room), two more figures alongside the fireplace in the studio, an acrobat on the back of the door to Clive Bell’s study, and, on a log box, a figure inspired by the Ballet Russes. In his home, as in his other paintings, Grant’s figures feel by turns classical and modern. There is a certain lyricism to these renderings, and yet they also feel monumental and bold. The two human forms that flank the studio fireplace are particularly revealing of Grant’s artistic sensibility. They are modeled after caryatids, large-scale stone carvings of women that were often used in place of support columns in Greek architecture. Grant’s painted figures metaphorically support the fireplace mantel above their heads, and yet their postures contain a level of dynamism and movement wholly his own. He understood the human figure as a visceral presence, containing both a kinetic momentum and a substantiality that feels nearly sculptural in its insistence on solid form.

They transformed Charleston into a house-sized painting, a piece of art in its own right.

Charleston allowed both Bell and Grant to develop many of the ideas they expressed elsewhere in their respective bodies of artwork. At Charleston, they could experiment freely, hone particular motifs, styles, and concepts, and make these ideas visible and omnipresent in the three-dimensional space around them. They could live alongside these visual vocabularies on a daily basis, facilitating an organic assimilation and evolution of their own creative interests.

Both artists were visual chroniclers of their family life, and in their other paintings Charleston frequently appears as a backdrop. Grant painted Bell inside the home, sitting on a sofa surrounded by books. Bell painted Grant sitting next to her husband, both of them drinking wine against the recognizable backdrop of their home’s hand-painted gray paisley Garden Room. In this way, they reproduced and continued to reinvestigate the visual motifs in their home through their other paintings.

For both artists, the experience of home required this attentive, repeated reinvestigation. As domestic spaces, homes have long sheltered not only families, but also ideas about families and how they should live. These conventional domestic expectations left little space for Bell and Grant or for their life together. The social norms of early 20th-century England certainly opposed the open romantic relationships Bell and Grant practiced. Beyond that, these domestic structures erased and excluded fundamental components of Bell and Grant’s identities and experiences.

For most of Grant’s life, homosexuality was illegal in England; the laws were not revised until 1967, when Grant was already in his eighties. Until late in his life, his very identity was codified against in British law as well as in its conceptions of home and family.

Domestic norms could also be oppressive in their constructions of gender. Homemaking circumscribed women’s experiences, tying them to certain household roles and expressly refusing them access to others. Bell embraced a radically different experience that encompassed both motherhood and her professional life as an artist. She was by all accounts deeply maternal, and within her family, she foregrounded her intellectual life and her artistic inventiveness right alongside her parenting.

For Bell and Grant, painting and repainting the surfaces of their house served as a means of reimagining domestic space. Through the act of painting, they reinvented and reclaimed a home where they could live out their identities more fully. As a family whose lives were excluded from traditional domestic experience, Bell and Grant worked to redefine what it might look like to live inside a household. They painted an entirely new way to experience the space of home.

At Charleston, Bell and Grant lived in close concert with their long-standing creative community, a group that became known as Bloomsbury. Bell’s sister, Virginia Woolf, lived nearby with her husband Leonard. Their old friend Roger Fry visited often—and contributed to several of the house’s key architectural redesigns. Other Bloomsbury friends came as houseguests or took up residence close by. The dining room at Charleston was a frequent gathering spot for this group of intellectuals and artists, who sat around the large round table Bell had painted, beneath a lampshade handcrafted by her son Quentin, which patterned the ceiling with constellations of dotted light. In centering their extensive intellectual community at Charleston, Bell and Grant again recast domestic space as a seat for values that resonated beyond their own family. The inventiveness of their interior decoration mirrored the environment they fostered for the people within it: one that embraced tolerance, open-mindedness, creative and intellectual engagement, and personal freedom.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Artists in Residence: Seventeen Artists and Their Living Spaces, from Giverny to Casa Azul. Used with the permission of the publisher, Chronicle Books. Text by Melissa Wyse, illustrations by Kate Lewis. Copyright © 2021 by Chronicle Books.

Melissa Wyse

Melissa Wyse is an art writer, fiction writer, and essayist. She has held fellowships and residencies at the MacDowell Colony, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and the Ragdale Foundation, and she is the recipient of an Individual Artist Ruby Grant from the Greater Baltimore Cultural Alliance. Her work appears in publications including The Rumpus, Shenandoah, Momus, and Urbanite. She received her Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing from American University and has taught writing and worked in the arts for many years. Wyse lives with her husband in Brooklyn, NY. You can find her at www.melissawyse.com and @melissa.wyse.